On a gray afternoon in Juneau, 36-year-old Kristen Hemlock sat on her bed picking at a cold McDonald’s chicken sandwich, waiting for the checks to arrive. Her four-year-old son, Eli, chubby and dimpled, lay on his stomach on a bottom bunk two feet away, distracting himself with YouTube cartoons. Six-year-old Mason wasn’t home from school yet, permitting a fleeting truce in the brothers’ perennial war over her phone. In a home the size of a dorm room, it was a more reliable source of entertainment than their toy trucks and guns. Broken drawers spilled out of a chipped wicker dresser, and fleece blankets, one patterned with the phrase “I love you to the moon and back,” blocked light from the lone window.

The boys’ father, 35-year-old Daniel Varner, sat at a tiny table in khaki overalls and work boots, jiggling his leg.

“It’s delivery mail, isn’t it?” he asked Hemlock.

“Yeah, so it might be tomorrow.”

“Oh yeah, it’s not coming. I was thinking post office box.”

“It could.” Hemlock emitted the nervous laugh she reserves for her saddest stories. “I’m hopeful.”

Most of the family’s 52 neighbors at St. Vincent de Paul Society’s transitional housing shelter, a faded blue building on the outskirts of town, were also waiting for money.

It was October 4, and pretty much everyone in Alaska was expecting it, with varying degrees of impatience—$1,600 for every man, woman, and child. For nearly four decades, the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) program, designed to share revenue from the state’s oil wealth, has made flat annual payouts to anyone who has lived there for at least one calendar year, barring those with certain criminal convictions. While the program’s architects didn’t use the term, it’s the closest thing today to a universal basic income program that has durably existed anywhere in the world.

Hemlock and Varner outside St. Vincent de Paul transitional housing in Juneau.

Ash Adams

The concept of universal basic income—in which governments pay residents a set sum regularly, no strings attached—has gained momentum in recent years. A growing chorus of Silicon Valley executives has called the policy inevitable, as automation threatens to displace one-third of American workers by 2030, raising the specter of unemployed masses rioting in the streets. Others have revived the idea as an efficient solution to poverty and inequality. Y Combinator, the tech startup accelerator, will soon test basic income with 3,000 people in two states, following a smaller study in Oakland, California. The city of Stockton, California, will launch a guaranteed income pilot in 2019, and lawmakers in Hawaii and Chicago are considering following suit. Trials have also launched in Barcelona, Canada, Finland, Kenya, Uganda, and Switzerland. In the United States, the concept is inching its way into the mainstream; Hillary Clinton’s campaign memoir disclosed she seriously considered floating a universal basic income program called “Alaska for America” during her 2016 run.

Inadvertently, red-leaning and fiercely independent Alaska has become a global model for advocates of doling out “free money.” After visiting the state in July 2017, Mark Zuckerberg, a vocal basic-income booster, wrote in a Facebook post that the dividend provides “good lessons for the rest of our country.” The dividend has been a third rail in Alaskan politics for nearly four decades. But just as the hype around basic income is growing, the program is facing an existential threat. Plummeting oil revenue has left the resource-dependent state—the only one with no sales or personal income tax—with multibillion-dollar deficits. Even after dramatic spending cuts, savings reserves are dwindling. The local GOP establishment, with backing from wealthy corporate interests, has blocked virtually all attempts to generate new revenue through taxes. With money running out, elected officials have slashed annual checks in half, despite their popularity. In May, lawmakers voted for the first time to divert $1.7 billion away from dividends to pay directly for government spending. While imposing income taxes would affect the richest Alaskans most, smaller dividend checks, and the program’s uncertain future, are hitting low-income families hardest.

“The PFD benefits the many, not the few. But a bank manager is telling me, “I don’t want to pay income taxes. I need your share,'” says Juanita Cassellius, co-founder of the nonprofit advocacy group Permanent Fund Defenders. “It’s a kind of class warfare.”

Until recently, Hemlock and Varner wouldn’t have noticed a dip in the dividend. After meeting in Bellingham, Washington, when they were both 19 and selling vacuum cleaners, the couple moved to Varner’s hometown of Petersburg, a fishing village in southeast Alaska, in 2015. As he had for most of his life, Varner spent much of the year on the water, hauling halibut, salmon, cod, herring, and five kinds of crab. In his best year, he made more than $80,000. In his worst, it was less than $20,000. Hemlock had studied to be a nurse but dropped out after having her first son. In Petersburg, she found a part-time job as a cashier at a bar and liquor store for $13 an hour. In 2016, the year Varner says “everything went to heck,” the couple didn’t apply for the dividend because friends wrongly told them they hadn’t lived there long enough to qualify. The $4,088 they could have gotten, Hemlock says, “would have saved us.”

That September while fishing, Varner fell from the deck into an aluminum storage tank and his back gave out. He missed the start of crab season, so the boat owner had to replace him. Then Hemlock lost her gig at the bar, where demand fell along with temperatures. The month their dividend would have arrived, they missed their apartment’s $2,400 rent payment. Then they missed another month. Four days before Christmas, though they’d cobbled together most of what they owed, they were evicted.

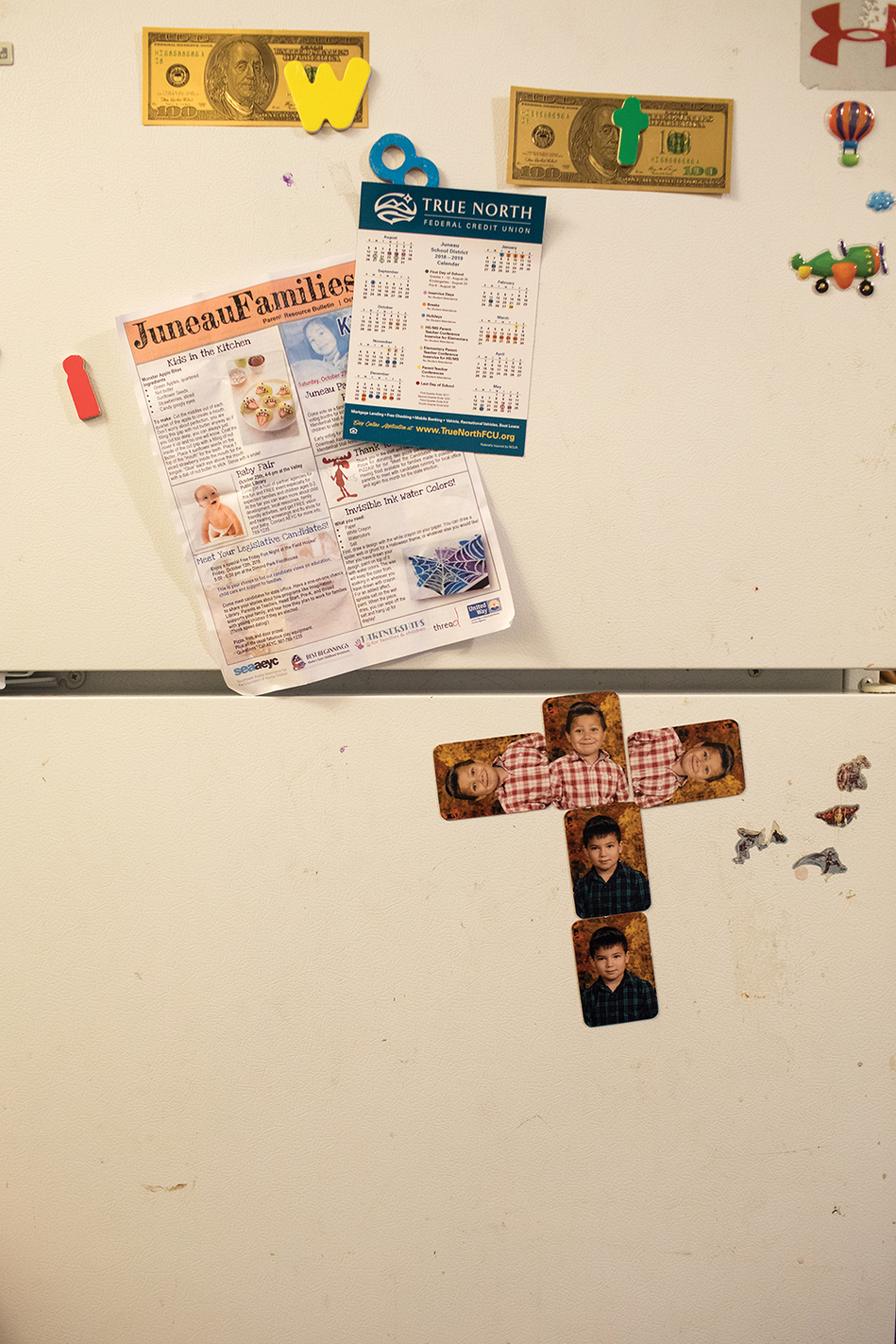

Eli and Mason, Hemlock and Varner’s sons, play on the bed in their home.

Ash Adams

The couple couldn’t afford to return to Washington, where their parents lived, so they and their sons moved in with Varner’s aunt, their only relative in town. But tension in the house soon forced them out. In January, Hemlock and her boys flew to Juneau, the closest city, and moved into a homeless shelter. Varner stayed behind earning $20 an hour helping an acquaintance open a legal marijuana shop. During the frigid nights, he squatted in a ballfield umpire shack. “It was our first experience of really being poor,” Hemlock says.

In May, Varner joined her in Juneau. Because men weren’t allowed at the shelter, he slept in the back of the family’s 2003 Dodge Durango and would often wake up to see bears circling his truck. He soon found a job running a seafood smoke room in town, where he worked 85-hour weeks for $10 an hour and later $14. His income replaced food stamps and welfare benefits, which had provided less than $800 a month. Without affordable child care for her youngest son, Hemlock couldn’t look for a job.

The family’s first dividend arrived that October, $4,400 in all. They used about half to lock in four months’ rent at St. Vincent de Paul, where they paid $525 a month for a room with a communal shower and kitchen. Another $750 went toward fixing the Durango—it was stuck in four-wheel drive, and steel wires showed through the tires. Hemlock bought the boys snowsuits and boots at Costco and paid $100 for two garbage bags of used clothing. She splurged on one night in a hotel—a substitute for a family vacation—and some Transformers toys to put under the plastic Christmas tree. The only thing she bought herself, for $100, was a decent camera phone to take pictures of her family. The money arrived just in time—later that month, Varner was laid off.

The following March, Varner started a job as a mechanic at a fish processing plant southwest of Anchorage. With more money flowing in, Hemlock stocked up on snow gear and on-sale clothes for the boys and signed them up for swim lessons and soccer camp. And she started looking for apartments in Juneau or back near their family in Washington. With basics covered, that fall’s dividend could fund a move. Varner would find a new job, and the family would reunite in a permanent home. Maybe they could even replace the Durango—it needed a new transmission, and the driver’s side door didn’t open. If the dividend was as high as the traditional formula dictated, they could expect about $12,000 combined. That might even be enough to make a dent in their student loans or Hemlock’s $5,000 in debt, mostly medical bills from her first pregnancy.

By the time the couple got their October 2018 checks, those hopes were dashed. In May, legislators had opted to slash the payment in half. The decision came at an inopportune time for Varner and Hemlock. In July, Varner had taken a bad fall off a forklift, damaging his spine. He kept working up to 110 hours a week because they needed the paycheck, but pains from injured disks mounted and his leg started going numb. He came back to Juneau, and now, sitting in the family’s room in St. Vincent de Paul, he didn’t know if he’d ever be able to lift more than 20 pounds again.

View from a window in Albert Oquilluk’s home.

Ash Adams

Varner, who is sinewy with a gap-toothed grin and a cross tattoo on his right arm, pulled out a bin of medicine bottles and began laying out pills in neat rows. “Right now, the pain is at a six at the best times,” he said. “And that’s a 10 being hot irons in my eyeballs.”

Varner had applied for workers’ compensation, but it wasn’t clear if or when funds would arrive or when he could work again. Every apartment Hemlock applied for had rejected them because of their past eviction. Instead of moving them forward, the smaller-than-expected dividend would now only cover their bills for the next few months. “We’re just inch by inch trying to climb out of this hole,” she said.

Had the government not reduced the payout, Hemlock surmised, her family could have advanced a new landlord extra rent to overcome the eviction on their record. They could have moved to Washington and reunited for good. “It would’ve changed our lives,” she said. “It would’ve gotten us out of this slump.”

“It’s criminal, what they do,” Varner chimed in. “It’s the people’s money.”

The dividend’s origins are rooted less in idealism than in greed. In 1968, nearly a decade after Alaska joined the Union, the largest oil field in North America was discovered on its northern coast at Prudhoe Bay. Lease sales filled the young state’s coffers with $900 million, more than five times its annual budget. Within five years, the entire windfall was gone. Much of it paid for education and transportation projects, but some politicians and members of the public felt that spending had overinflated the bureaucracy. Jay Hammond, a trapper and fisherman elected governor in 1974, declared that the “nest egg” had been “scrambled.” He and other leaders decided the state ought to safeguard some oil revenue for future generations. In 1976, voters approved a constitutional amendment creating the Permanent Fund, a savings account that would be managed by a semi-independent, state-owned corporation and would take in at least a quarter of oil royalties and related income and invest it.

The fund’s principal could never be touched, barring a constitutional amendment, but Hammond strongly believed the earnings should go directly to residents. The self-styled “bush rat governor” had no interest in charity or wealth redistribution. Rather, influenced by consultants like Milton Friedman who advocated a federal basic income, he viewed recipients as shareholders that should benefit equally from ownership in “Alaska, Inc.” and could spend money more efficiently than the government. Hammond reasoned individual distributions would give the public a personal stake in keeping the fund safe—were politicians to fritter away or mismanage the savings, it would hit every resident right in the pocketbook. If oil was, in the words of OPEC’s founder, “the devil’s excrement,” breeding waste and corruption, Hammond argued a dividend would “at least halfway pin a “diaper'” on it.

As the young fund slowly built up principal, lawmakers debated how to spend the earnings. Most of them strongly opposed dividends, preferring to fund infrastructure or loans to small businesses. Many feared handouts would attract “freeloaders” to the state, or that people would stop working or waste money on frills and vices. But when oil prices soared after the Iranian revolution, there seemed to be enough revenue to go around. In 1980, legislators repealed individual income taxes and put the fund to use, enacting a dividend that would give every adult Alaskan $50 for each year they’d been a resident since statehood. The US Supreme Court ruled the seniority provision unconstitutional, so legislators replaced it with flat annual payouts, extending them to children and adding provisions that prevented recipients from losing federal public assistance because of any windfall. In 1982, Alaskans received their first checks of $1,000. It was the first time in contemporary history that a government had sent money to people just for living in its jurisdiction.

While not intended as a progressive social policy, the dividend has proved extremely effective at reducing poverty and improving welfare. In all, the state has doled out more than $22 billion in unconditional cash assistance. About 630,000 people, roughly a quarter of whom are children, received payouts in 2017, with the average household getting nearly $5,000. Economists agree the dividend is the main reason Alaska boasts the second-highest income equality in the nation. Researchers from the University of Alaska-Anchorage estimate it lifts between 15,000 and 25,000 people out of poverty each year and reduces the number of Alaska Natives living in poverty by a quarter. It has even been credited with increasing birth rates and weights. A 2017 survey funded by the Economic Security Project, a pro-basic-income group, found that about 80 percent of Alaskans feel the dividend improves their quality of life and is an important source of money for their community.

No one has comprehensively analyzed how the dividend affects the state’s economy, but there’s evidence that the money “trickles up.” Scott Goldsmith, a retired Anchorage economist who has studied the policy since its inception, estimated that a dividend of $1,300 creates 10,000 jobs, attracts up to 20,000 workers to the state, and adds $1.5 billion to personal incomes in the year it’s doled out. Concerns that a permanent payout discourages work appear unfounded. In 2018, economists at the University of Chicago and the University of Pennsylvania concluded the dividend had no overall impact on employment, likely because any labor force dropouts were balanced by new jobs created to meet increased demand. Juneau’s finance director estimates 2018’s checks generated up to $1.4 million in sales tax revenue for the city. Bill Popp, president of the Anchorage Economic Development Corp., says the city, whose residents receive about 40 percent of the total payout, has seen a major boost in retail, restaurant, and hotel revenue, as well as surging demand at local clinics, dentists, and optometrists.

How much of their checks people spend—and on what—has been a matter of debate. A 2003 study found no increase in consumption after dividends went out, but recent research found evidence for a spending bump in the ensuing three months, especially from higher-income households. Annual “PFD specials” from airlines and hotels and increased business for marijuana shops and vendors of pull-tabs, one of Alaska’s only legal forms of gambling, fuel the feeling among some that checks go to waste. Researchers have found that mortality in Alaska’s cities increases by 13 percent the week checks arrive as consumption increases.

But surveys suggest most people use their checks prudently. Nearly 60 percent of respondents to the 2017 Economic Security Project-commissioned study said they saved most or all of their dividend or used it to pay off debt. When people spent their checks, 65 percent said it was on everyday bills and expenses. A quarter said they paid for major purchases like appliances, car repairs, and home improvement. In 2017, about 7 percent of dividend funds were garnished, primarily for child support, and people opted to donate more than $2.5 million to charity while applying for the dividend online.

Carolyn Oquilluck, whose family used part of their checks to pay off debt, prepares to make a traditional dress at her home in Teller.

Ash Adams

Public support for a dividend was tepid before its launch, but it soon became the state’s most popular policy, with backing across party lines. Officials have regularly tried to cut payouts, particularly in lean years, but just as Hammond intended, those attempts have historically spelled political suicide. After oil prices cratered in the late ’90s, an advisory ballot question polled voters on whether a portion of the fund’s earnings should go toward closing the state’s general budget deficit; 83 percent said no. If anything, support for dividends has intensified over time. The Economic Security Project survey found that 58 percent of respondents would rather pay new taxes than give up a portion of their dividend. The anti-tax Alaska State Chamber of Commerce’s own 2018 survey found that 35 percent of Alaskans were open to new taxes to balance the state’s budget; only 9 percent were open to using fund earnings.

Despite popular opinion, for the past three years, with oil prices still low and Alaska facing annual budget deficits of up to $3.7 billion, lawmakers have finally resorted to cannibalizing proceeds of the Permanent Fund, whose protected principal is now worth more than $46 billion. In 2016, Gov. Bill Walker issued a veto that cut the amount that legislators had set aside for dividends in half. (Based on a statutory formula, Alaskans typically share half of the five-year average of the fund’s earnings.) Three current and former legislators sued the state, but Alaska’s Supreme Court upheld the governor’s right to reduce payments. Over the following two years, legislators kept the checks at the new lower levels. Last spring, for the first time ever, lawmakers used $1.7 billion of fund earnings for government expenses and passed a law allowing them to continue to do so in the future. If the trend keeps up, some fear it could eventually spell an end to not only dividends but the Permanent Fund itself.

Spending the fund’s earnings has so far allowed legislators to avoid raising taxes. But reducing the size of dividend checks has effectively instituted a regressive tax that, for every $100 million funneled to the state budget, costs the poorest Alaskans 3 percent of their disposable income. “This is economic warfare at its worst,” says Rick Halford, who was the Republican state House majority leader when the dividend was established and one of the plaintiffs in the 2016 suit against the state. “It’s the haves versus the have-nots.”

Less than 150 miles from mainland Russia, the Iñupiaq village of Teller, population 228, sits at the base of a tiny sandspit on the edge of a bay bordering the Bering Sea. Unlike many Alaska Native villages, which are only accessible by plane or boat, Teller can be reached by a gravel road that winds through rust and ocher tundra meadows, interrupted by creeks and trampled by herds of reindeer and musk oxen. Beyond the beached skiffs and the sliced salmon draped over wooden racks, on Whale Street (if you hit Walrus Street or Sled Way, you’ve gone too far), a hand-painted sign marks the Teller Native Store, the only place in town selling groceries.

Inside on a Sunday afternoon, Albert Oquilluk lifted a freezer lid. Nothing but reindeer meat, at $14.49 a pound. “Usually, we just go out and get our own,” he said. Trailed by his six-year-old son, Urijah, he moved to a pair of refrigerators and peered at the racks. “No sausage, no bacon.” He threw a can of Spam in his shopping basket.

Albert Oquilluk and his youngest child, Urijah, 6, eat dinner while Kailey and Carolyn sit on the sofa.

Ash Adams

Most autumns, Oquilluk would have had stores of dried salmon at home, or he’d be out shooting ducks and geese. This year, he’d been lucky enough to land a temporary job as a heavy-equipment operator helping build a new dumping ground for the sewage that villagers collect in “honey buckets.” (Most homes don’t have plumbing or running water.) Normally, his only steady pay was a $125 monthly stipend for sitting on the tribal council, with some money on the side from plowing snow or driving people to clinic appointments. Oquilluk’s wife, Carolyn, works for the local government, but some years the family ends up on food stamps. The construction wages were a welcome boon, but he’d been working 10 hours a day, six days a week, since June. That left no time for fishing and hunting, which most villagers still do to supplement their diets.

Oquilluk is 48 with a round face and salt-and-pepper hair. He tossed a quart of ultra-pasteurized milk into the basket, then Krusteaz pancake mix, Sailor Boy Pilot Bread Crackers, Sun-Maid FruitBits, grape Kool-Aid, and 27 Otter Pops. Canned sweet potatoes, pickles, and pickled beets went in, too. There were no fresh fruits and vegetables—those had to be hauled or shipped from Nome, a small city about two hours away, or foraged in the form of wild berries or “beach greens.” Urijah sneaked some Goldfish crackers into the basket, and his father threw in a tin of beef jerky. The total for 11 items and the mess of Otter Pops came to $81.22.

The family’s dividends had arrived two days earlier and were paying for the groceries. All together, Oquilluk, his wife, and their four kids had gotten $9,600 after the cuts. Even given their flush year, that sum made up about 15 percent of their income. In leaner times, they needed the dividend to survive. Rural Alaska is expensive, with gas for their truck and boat costing more than $700 a month. Groceries top $1,000. This year, the money helped them buy things beyond the basics. Oquilluk and his wife had already spent about $2,000 on Amazon. They bought raw honey, kids’ clothing, boots, a boot dryer, a burger press, tongs, bowls, a come-along for hauling boats or marooned four-wheelers, a jigsaw for carving a traditional crescent-shaped knife called an ulu, a bucket seat cushion, a smartphone attachment for their spotting scope, and eight pounds of lard. They were thinking of splurging to send one of their daughters to attend tribal conferences in Anchorage.

Most importantly, they paid off some of the $5,000 plus late fees remaining on their loan for an 18-foot skiff and motor, which Oquilluk had bought so he could fish. “We’re almost three years overdue on payments. When they started cutting our PFDs, that’s when we couldn’t make a payment.”

The Oquilluks are better off than many of their neighbors in Teller, where almost 40 percent of residents live below the poverty line and income per capita is less than half the national median income. For some, the dividend is the only cash they get all year besides public assistance. Dividend checks play an amplified role in rural Alaska, with its isolation, lack of jobs, high living costs, and less reliable public services. Researchers at the University of Alaska-Anchorage estimate that eliminating dividends would increase the number of Alaska Natives living below the poverty line by about a third and boost poverty among elderly Native people in rural areas by 72 percent. Thanks to his job and the dividend, Oquilluk said, “we’re making ends meet.”

In some ways, the role the dividend plays in rural Alaska is similar to what advocates say a universal basic income could do: fill the gaps when there aren’t enough jobs to go around. Alaska’s dividend is not high enough to represent what advocates call a full basic income, defined as being enough to survive on and escape poverty, either on its own or combined with social services. But given that its payments are regular, unconditional, and doled out to virtually everyone, the Permanent Fund Dividend is the closest thing to an institutionalized universal basic income in the world today. For proponents of expanding the idea, the lessons are clear: Universal direct cash distributions work. And they become wildly popular once enacted, with beneficiaries even in an individualistic, conservative state finding ways to justify a government entitlement elsewhere embraced by radicals and leftists.

Some Alaskans say the dividend is unique because it’s funded by a jointly owned natural resource, and they view the payouts as everyone getting a fair share, rather than money coming out of someone’s pocket. If “the general public can identify it as their money going to their neighbor, who they’re mad doesn’t work, then it’s going to be trouble,” Halford says.

Basic income advocates say the United States could fund a similar federal policy without hiking personal income taxes by taxing things like financial transactions, carbon, or shared natural resources. Andrew Yang, an entrepreneur and booster of universal basic income who wrote a book about the idea, says that “Americans recoil at the idea of a handout or money for nothing, but if you frame it as a dividend people receive as shareholders of the richest, most advanced society in the history of the world, then the attitude toward it can change very quickly. Alaska is a phenomenal illustration of what’s possible in the rest of the country.”

Juneau, Alaska, where Kristen Hemlock lives in transitional housing with her partner, Daniel Varner, and her two young boys, Eli and Mason.

As policymakers around the world look to universal basic income, it’s unclear whether Alaska can afford to keep its pioneering program alive. Petroleum revenue has constituted more than 80 percent of the state’s income in some years, but oil production is just a quarter of what it was 30 years ago, and the state projects it will continue to decline. The savings accounts legislators previously tapped to fill deficits have drained from about $16 billion to just $2 billion over the past five years. Over the same period, the state budget shrank by nearly 30 percent. Beyond slashing it further, an obvious option is to generate revenue by introducing an income or sales tax, hiking property taxes, or squeezing more out of corporations. Bill Wielechowski, a Democratic state senator and ardent dividend supporter, argues that cutting oil and gas tax giveaways alone would go a long way toward eliminating the deficit. Since 2006, the state has spent a total of $3.6 billion on cash subsidies for oil companies, and though the program was repealed in 2017, it still owes more than $830 million in unpaid claims. In addition, Alaska forgoes substantial tax revenue every year—a projected $1.4 billion in 2019—through tax breaks to oil and gas companies.

Even though raising taxes is more popular among Alaskans than eliminating dividends, the idea is anathema to the state Republican establishment, wealthy constituents, and corporate interests. In 2016, when the state faced a deficit of $3.7 billion, Gov. Walker, an independent, proposed reintroducing personal income taxes, raising taxes on fuel, alcohol, and cigarettes, and hiking levies on oil, fishing, and mining. Pete Kelly, a Republican who co-chaired the state’s Senate Finance Committee, offered a brusque response: “I wish I had some pithy comment to express my disdain for taxes, but I don’t. So for now, I’ll just say no.” Walker’s proposals died in the Legislature. The following year, the House passed a small income tax, but the bill failed in the Republican-controlled Senate.

Anti-tax campaigns were bankrolled by Alaska’s chamber of commerce, whose lead sponsors include the biggest oil companies operating there; the local wing of Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity; and investor Bob Gillam, one of Alaska’s richest men. In 2016, Anchorage-based telecommunications firm GCI spent more than $2 million on a lobbying and advertising campaign to push the use of Permanent Fund money to pay off deficits as its CEO, Ron Duncan, warned the only alternative was “unsustainable” taxes or budget cuts. While the dividend was created largely by conservatives who preferred handing out money over services, today’s right-wingers seem prepared to gut both. If taxes stay a nonstarter, lawmakers will likely resort to diverting dividend checks and using the Permanent Fund Earnings Reserve Account, worth $17 billion as of September, as a new piggy bank. Based on a bill the Legislature passed in May, officials can withdraw $2.9 billion for the next budget. How much will go toward checks versus paying the government’s bills is up to lawmakers.

For now, the dividend seems to remain a sacred cow—but so does the anti-tax mantra. In November, Alaskans elected former state Sen. Mike Dunleavy, a conservative Republican, as governor. His campaign platform centered on restoring full payouts, with slogans such as “Save the PFD” and “A vote for Dunleavy pays dividends.” The future of the dividend was perhaps the top issue in the race, and Walker’s poll numbers fell steadily after he slashed PFD payments. (He dropped out less than three weeks before the election.) Dunleavy has promised to protect the dividend fund and not reduce payments. But the governor-elect firmly opposes raising taxes, leaving open the question of how he would balance the budget, short of further gutting government services. “He’s going to run into an economically and politically untenable position,” Wielechowski says.

In an essay published after his death, former Gov. Hammond wrote that failing to veto a repeal of Alaska’s state income tax in 1980 was one of his biggest regrets. In his mind, Alaskans’ addiction to no- or low-cost government services was a much more pernicious form of “freeloading” than anything decried by critics of the dividend. Imposing income taxes would affect higher-income residents the most, but dividend cuts disproportionately hurt the poor. Pretty soon, Alaskans will have to choose which habit to kick.

“Somebody’s going to have to pay,” says Matthew Berman, a professor at the University of Alaska-Anchorage. “As economists like to say, there’s no free lunch. So whose lunch are you going to eat?”

This story was produced with support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.