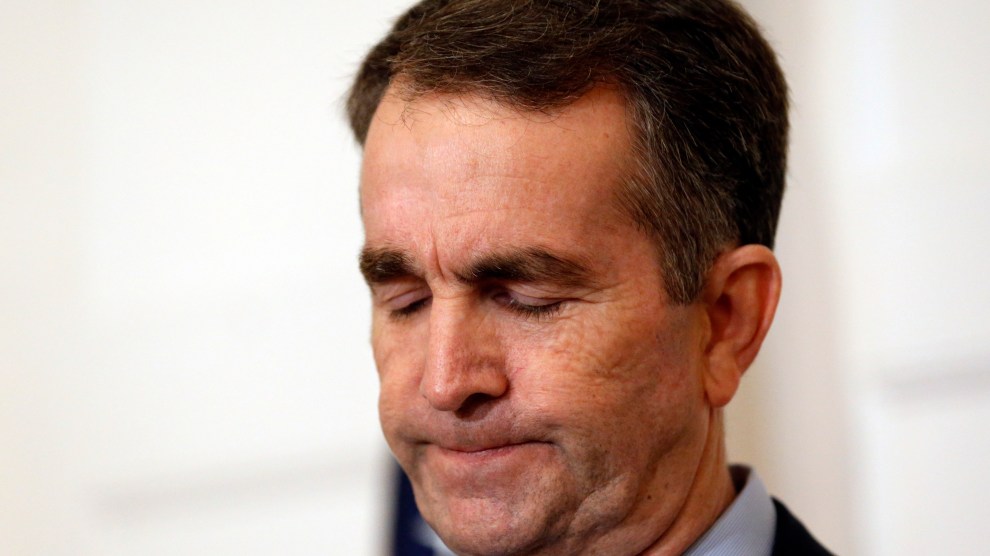

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam pauses during a news conference in the Governor's Mansion in Richmond, Va., on Saturday, Feb. 2, 2019. Steve Helber / AP

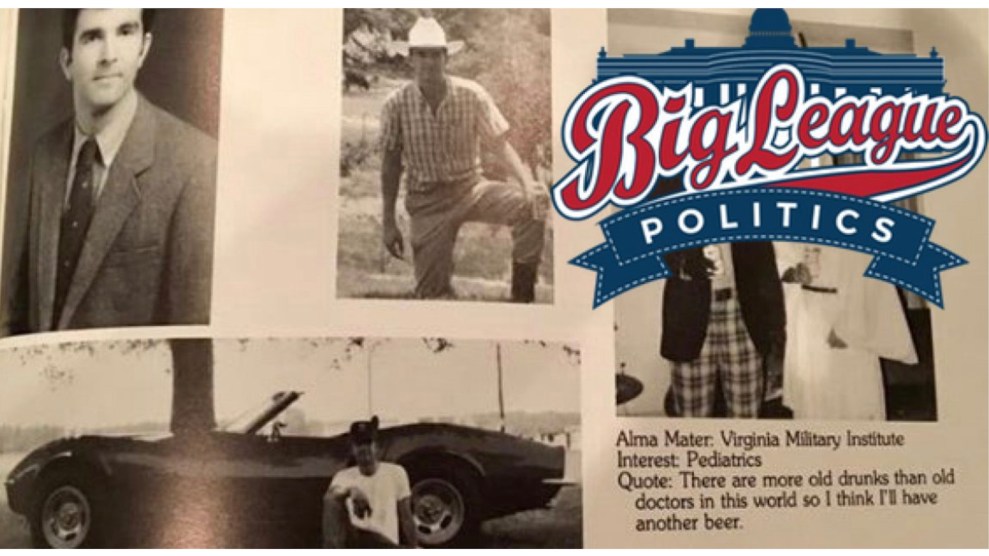

“Yes,” declared a Virginia politics blog, “this is chaos.” After Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam clumsily defended a bill that would roll back a number of abortion restrictions, including rare abortions in the third trimester, a former medical school classmate sent a tip to (then) little-known conservative media outlet Big League Politics. The publication, which has ties to white nationalists, published a photo of Northam in blackface from his medical school yearbook.

Amid calls for his resignation, Northam stumbled. He bungled his apology; he joked about dressing up as Michael Jackson. Now, it seems his advisers have assigned Northam some reading: Ta-Nehisi Coates and Alex Haley’s Roots. But he avoided talk of resignation, in part, because the rest of the top-tier of Virginia’s government is now engulfed in scandal too, potentially jeopardizing Democrat leadership. Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax (D-Virginia) is facing allegations of sexual assault; Attorney General Mark Herring admitted he also wore blackface in college. It’s unclear what will happen next, but culturally, something already has: In Virginia, racism can now endanger political power.

Peter Wallenstein, a history professor at Virginia Tech and longtime civil rights scholar, says that’s new. “Any and all who take exception to the world of white supremacy…take exception to blackface as the image du jour of a world that must die and yet will not die,” he noted.

“That yearbook page has been there for the longest time,” Wallenstein points out, but only now is it being called into question.

Wallenstein guessed that anyone who is “male and white and in the South…just might be at risk” of public scandal brought on by past racist acts. Hours after Wallenstein spoke with Mother Jones, news broke that Virginia’s Republican Senate leader edited a yearbook that featured blackface photos as well as racist slurs, and a reporter in North Carolina unearthed yearbooks that showed fraternities using blackface at parties.

Mother Jones: Has anything quite like what’s going on there in Virginia ever happened before?

Peter Wallenstein: Blue lightning just struck three times in a row. There’s no model for this. There’s no model for taking out not only the top guy but the next two as well. And there’s no model for having the top three represent one political party but the House of Delegates and its Speaker be on the other side.

And I go back 50 years—and then 100, 150, 200—everything is flipped, right? The way you run a campaign, the way you win office, the way you govern, is by demonstrating, overtly, the most thoroughgoing racism that’s possible. That way your commitment to white supremacy can’t be in any way doubted. So, this really is just it is astonishing on so many levels.

MJ: Do you see this as a pretty large structural shift in Southern politics then? The idea of potentially resigning because of racism?

PW: Well, I do in some respects. There’s a whole lot of unmooring going on, a whole lot of disorientation, and the good governor himself demonstrated that with this pathetic press conference performance. But I think that he’s kind of a metaphor for—a proxy for—a widespread sense of: “What is going on?” Sands are shifting in ways that it’s hard to fathom.

On the one hand, there’s a deep disappointment in what’s been. On the other hand, it’s a revelation that we live in a world where suddenly this issue could become the most salient possible one. Nothing about that was predictable either. It’s a variation on the #MeToo movement—suddenly it erupts. It isn’t like the issue wasn’t always there. But it was subterranean, invisible, taken for granted.

MJ: How long has minstrelsy and blackface been a part of Southern life?

PW: Actually, I broaden it out, because this is a national phenomenon. I grew up in New Hampshire and remember vividly a minstrel show. This wasn’t an import; this wasn’t a passing circus. This was town folks putting on this performance to which all were invited. And there I am, as I don’t know, maybe a 10 or 12 year old, watching this performance, and watching this so-called “interlocutor”—a word I’d never heard before, a word I haven’t heard much since either. He lived across the street from me. And he was a good man, and a good neighbor, and he’s saying these kinds of things that even in my primitive political stance—well, I was horrified.

Minstrelsy may have been more occasioned and have been more frequent in the South, but I’m thinking it’s more like the 1920s Klan: this is a national phenomenon. It’s more sharply etched in the Southern landscape, it’s more pervasive, but it’s national.

MJ: Have there been other times where race has so obviously played a role in Virginia politics?

PW: It’s race that most obviously surfaces whenever I think about the past of politics in Virginia. And it really doesn’t matter where you put your foot down in the slime. You’re going to find it in the 17th century, 18th, and 19th. I wrote years ago about George Mason, one of the illustrious founders out of Virginia, and how stridently he argued against ratification of the Constitution because—to use his rhetoric—it was insufficiently pro-slavery.

Then, the secession was all about white supremacy, and it had all kinds of appendages, all kinds of dimensions, but you had to keep slavery. That was the big question for so many delegates to the secession convention: “Is it true that slavery will be safer if we go out of the Union than if we stay in?” That question is kind of a proxy for two centuries’ worth of politics in the state of Virginia.

Then in 1965, Mills Godwin runs for the governorship. He has just the previous year supported Lyndon Johnson for the presidency. (And he broke with Harry Byrd, so he was persona non grata in some quarters.) But this is the same guy who, less than a decade before, had been one of those chieftains of massive resistance—we’re prepared to shut the school downs, get out of the public education business, rather than permit one black kid to sit next to one white kid. So that’s the politics of Virginia in the 20th century.

Now, things have settled down in a way, in that racism is far less obvious. In fact, one of the shining moments in modern Virginia history would be just five years after Godwin runs for the governorship when his successor, Governor Holton—a Republican of all people—gets elected and he chooses to walk his preteen daughter off to her new black high school to demonstrate that desegregation can work, it should work, and I’m going to model it. There’s a situation that’s remarkably different from the current one in some respects, and very similar in one crucial respect: the world has turned.

MJ: I wanted to talk about that idea of things radically changing in one’s lifetime. You saw this happen with a lot of Southern politicians. They explicitly supported segregation; then, they recanted later on. What do we make of those performances of apology? What do you make of Northam’s?

PW: Certainly, Northam is embarrassed, there is no question about it—to be associated with this kind of imagery. Now, how he handles it is another thing. “I’m deeply sorry.” Then, “No, no actually that wasn’t me.” Then, “But I did that thing just not there.” That stutter-step kind of performance is itself pretty poor.

MJ: Let me go broader to the question of changing values though. C. Vann Woodward famously gave speeches at UVA after Brown v. Board, that said, basically, there’s hope that even if people are stuck in their racism, laws can help change that because laws affect beliefs even if people aren’t ready. Is there hope in the fact that beliefs have changed to where a yearbook widely accepted at the time is now a problem, and that we can continue to change?

PW: Woodward is a really interesting figure. His central thesis was that we can hope because we have a past that embodies, at least in a tepid kind of way, the kind of world we’d like to create. It was very influential. He was saying that segregation had to be created and imposed—that it wasn’t always there. He produced all kinds of examples where black and white jostled together in the post-war Civil War South during Reconstruction, and society didn’t seem to crumble as a consequence. So there are two things there. One, law had changed the behavior—enforced a pattern of behavior that wouldn’t otherwise naturally have erupted. So, he could be optimistic that, yeah, change the laws after Brown.

Let’s take another example. When the Loving ruling was handed down by the Supreme Court in 1967, there was some resistance by judges who didn’t want to issue licenses. But those were all cleaned out in quite a hurry. Now, it didn’t immediately change either black or white resistance to the notion that their kin should marry across the racial line. But, immediately, people who had wanted to get a license could get a license. People who had wanted to move to a state and take their marriage with them could do that. And now when I look across a college campus today—I’m even more struck this year than last—there is every conceivable combination of racial and ethnic terms. To the extent that these are visible, you can say, “Yes, and that’s a world that a Supreme Court ruling made possible by overriding state law that had been in place since the colonial period.”

Does the law change behavior? Yes, in some respects. Does it permit the kind of behavior that would have been in the absence of that constraining law? Yes. So, you got two different directions to go forward. There is grounds for optimism, no question, and there’s a lot of embodiment of the basis for that already out there. The clearest example would be precisely the firestorm that erupted.

MJ: When you look at the college campus—and you look over in Charlottesville—there was a different kind of eruption. There’s a way of seeing it pessimistically. There is this agency and ability. We have control, more than we might realize, through who we elect and who we permit in the public discussion to change how things go forward.

PW: Well, exactly so. Another historian, Louie Hartz, talked about “cultural fragments.” In his world, he was talking about how the Quebecquois in Canada are different from the French left behind in France; how the two societies had moved off in different directions. And what I see across campus, across the state, across the nation, across the world is these are cultural fragments. It’s not like you move from one mindset that’s homogeneous to another mindset that’s homogenous and there’s somehow transition between the two. The transition is really pretty rocky.

In fact, the earlier version persists even as the second one comes into view. And the notion that progress—or whatever we think of as progress—just ratchets forward and never can slip back, that’s a really dangerous conceit.

If you take out the top three leaders in the government, and suddenly the Republicans control both the governorship and the legislature—both branches—and so the kinds of things that people voted Democrat thought as progress, suddenly all that’s at risk too. All that’s up for grabs again. So, there’s a tremendous amount going on. And it goes far beyond what the president tweeted earlier today about how he thinks this can flip Virginia.