Scott Olson/Getty

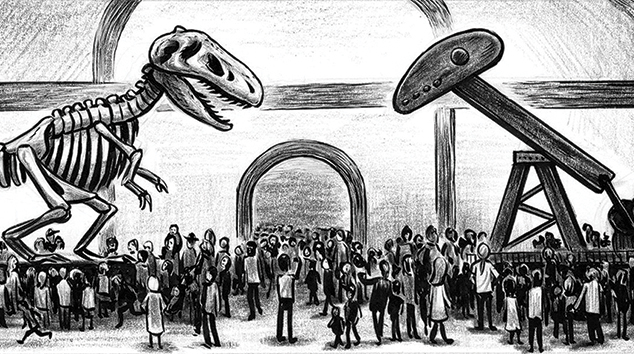

Each year since the Paris climate agreement, major world banks have increased their financing of fossil fuels, pouring $1.9 trillion into the industry from 2016 through 2018. And, it turns out, US banks are the worst offenders, according to a recent report published by a group of environmental organizations.

“The sad reality is that the fossil fuel sector has only grown since Paris,” says Patrick McCully, climate and energy director for the Rainforest Action Network and one of the report’s authors. “The banks are following what the industry is doing, and the industry’s able to expand because it’s able to keep getting capital from the banks…It’s just this really alarming, really terrifying dynamic going on worldwide.”

The top four financial institutions supporting the fossil fuel industry are all American: JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citi, and Bank of America. Two more, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, aren’t far behind. This is despite all six of these major US banks publishing a joint statement, in the months leading up to the adoption of the Paris deal, acknowledging the threat of climate change, pledging financial support for solutions, and calling for a “more sustainable, low-carbon economy.”

By far, JP Morgan Chase is the biggest funder among the 33 banks assessed, putting $196 billion into fossil fuels from 2016 through 2018. Its money represents 10 percent of the industry’s total financing. Notably, the highest spending year for Chase—and many other top banks—was 2017, the same year President Trump announced the US would pull out of the Paris agreement.

In recent years, public pressure has mounted against banks financing oil, gas, and coal companies. These campaigns have been particularly coordinated and successful in Europe, and the World Bank announced in 2017 that it would no longer finance oil and gas extraction. The same year, France-based PNB Paribas committed to end support of shale and tar sands businesses, and last year, British multinational HSBC stopped financing offshore oil and gas projects in the Arctic.

“There’s new legislation and national legislation in European countries that are forcing banks to move in the right direction much, much quicker than the US banks,” McCully says. “[US banks] don’t feel the same sort of public pressure, and they definitely don’t feel the same sort of political pressure.”

Efforts and success in the US have been more limited. The most pressure so far has come from activists, led by indigenous groups, that have targeted banks supporting the Dakota Access pipeline. Protesters have also rallied outside Chase and Wells Fargo over their fossil fuel funding in recent years. But the United States is home to several of the world’s biggest oil and gas companies, including Exxon Mobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips, and the industry holds huge political influence, particularly since US production of fossil fuels has surged over the past decade. In 2018, lobbying for oil and gas topped $124 million—more than double what it was 15 years ago—putting significant pressure on politicians to resist climate action despite dire warnings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that the world has just over a decade to act to avert catastrophe.

“Our financial system is basically not responding to that threat at this point,” says Yossi Cadan, the senior global campaigner on divestment for 350.org. “The notion that politicians are not going to act is the current financial assumption. And if you think like that, and you say, okay, politicians are not going to regulate the extraction of fossil fuels…then we may be able to burn everything that we have and make a profit out of it.”

Still, banks have made very public commitments in recent years to finance sustainable companies and projects or to go carbon-neutral. Last year, Wells Fargo, the second biggest fossil fuel funder, committed $200 billion in financing through 2030 to projects and businesses focused on transitioning to a low-carbon economy. In 2017, the institution invested $12 billion in sustainable businesses—but it put more than four times that toward financing fossil fuels the same year.

Citi, Bank of America, and Chase have made similar pledges, all of which pale in comparison to their fossil fuel financing. In 2017, Chase announced it would be 100 percent renewable energy–reliant by 2020 and committed $200 billion in clean energy financing by 2025. But it has spent almost the same amount financing fossil fuels in just the past three years. And while Chase CEO Jamie Dimon publicly criticized President Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris agreement, the bank’s longest sitting board member is Lee Raymond, the former board chair and CEO of Exxon. Well known for his public skepticism of climate change, Raymond led Exxon during a time when it was pouring tens of millions of dollars into funding climate change denial.

The report also reveals that Chase is the top financier of three major categories of fossil fuel projects—Arctic oil and gas, ultra-deepwater drilling, and liquefied natural gas—and that it is also the top US banker for two others: tar sands oil and coal mining. It is second only to Wells Fargo in financing fracking. Chase did not respond to requests for comment from Mother Jones.

The broad increase in fossil fuel funding comes as many people consider fossil fuels to be economically unsustainable. Oil and gas companies face the prospect of stranded assets if governments tighten environmental regulations, if energy demand shifts toward renewables, or if companies face litigation and increased scrutiny from concerned shareholders—all of which are currently underway. The coal industry in the US is on its last legs, despite the Trump administration’s efforts to prop it up. About 75 percent of US coal production is more expensive than solar or wind energy, according to a report released this week. And it’s getting harder for the industry in general to make money. Yet oil companies have continued to aggressively pursue fossil fuel development, and the world’s major banks are supporting them. Alarmingly, the new data shows that banks (again, led by Chase) put $600 billion behind the 100 companies most focused on expanding fossil fuel production, accounting for almost one-third of all fossil fuel financing.

“Even if the bank thinks in seven years it might be a problem, they say, ‘Well, we’ll be out of here in three years,'” McCully says. “You say economically why would they do it, but even morally why would they do it? If they think they’re leaving this completely decimated world to their kids and grandkids, wouldn’t they want to do something about it? But it just seems like they’re unable to look beyond the next quarter, maybe the next year. They just don’t have long-term economic or moral vision.”

As banks become increasingly crucial to the future of fossil fuels, they could also play a particularly critical role in the fight to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and slow global warming. Without the support of banks, US coal companies would be decimated since a lack of liquid assets makes them reliant on loans, Cadan points out. And while oil companies have enough assets to finance themselves for a while, it’s largely unsustainable long-term, especially because without financing, new investments are increasingly risky and costly. Banks “can determine the pace of how we combat climate change,” Cadan says. “It’s black and white. With the help of financial institutions we can easily be in a different space. If they take real action.”

“Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how many solar panels we have,” McCully adds. “If we’re still building lots more coal plants and oil fields, clean energy is not going to help.”