Mother Jones illustration

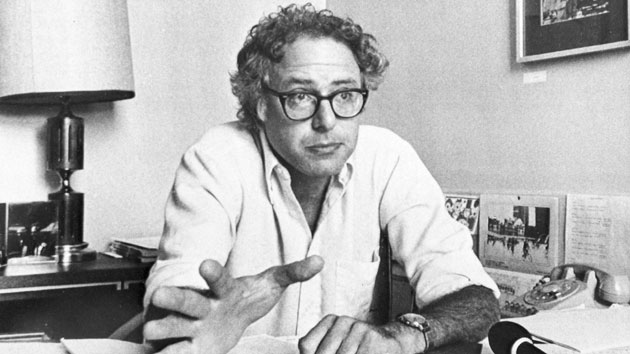

Sometime in the mid-1980s, about halfway through his eight-year tenure as mayor of Burlington, Vermont, Bernie Sanders flipped to a fresh page in a yellow legal pad and poured out his crippling sense of doubt.

“What can be done?” he scrawled.

“What is hard to see through is the total”—he scratched out “total” and tried again—“almost total degree of powerlessness which presently exists. We can make almost nothing happen.”

Sanders laid out a series of frustrations. He was fighting with the state over where the city dumped trash; there was a labor dispute at the fire department; the police department was in turmoil. The revolution in city government he had promised as a candidate in 1981 had become mired in the mundane.

“Maintaining a radical vision is extremely difficult when one is confronted on every corner with the force of suffocating force of the status quo,” he wrote.

Sanders’ mayoral papers, which are open to researchers at the University of Vermont, include dozens of legal pads that the Democratic presidential candidate filled with speech drafts, schedules, brainstorms, and doodles. But the pads also include confessional notes that Sanders wrote to himself. The memos, which were not reported during his 2016 run for president, offer a glimpse of the Democratic presidential candidate on the cusp of middle age, agonizing over the prospect of personal and professional failure, even after a succession of improbable political victories.

Sanders did not keep a regular journal, and the mostly undated memos are scattered haphazardly amid his other work. But based on their contents, they were largely composed in the run-up to Sanders’ unsuccessful 1986 campaign for governor, at a pivotal juncture in his career. By early 1985, he had won three elections for mayor, and he had steered the city on a decidedly leftward course, taking on cable companies and developers and cultivating a national and international profile. But as Sanders considered his own future, he fretted over whether his time in Burlington would be a stepping stone or the end of the road.

An August 1985 memo was illustrative of Sanders’ angst:

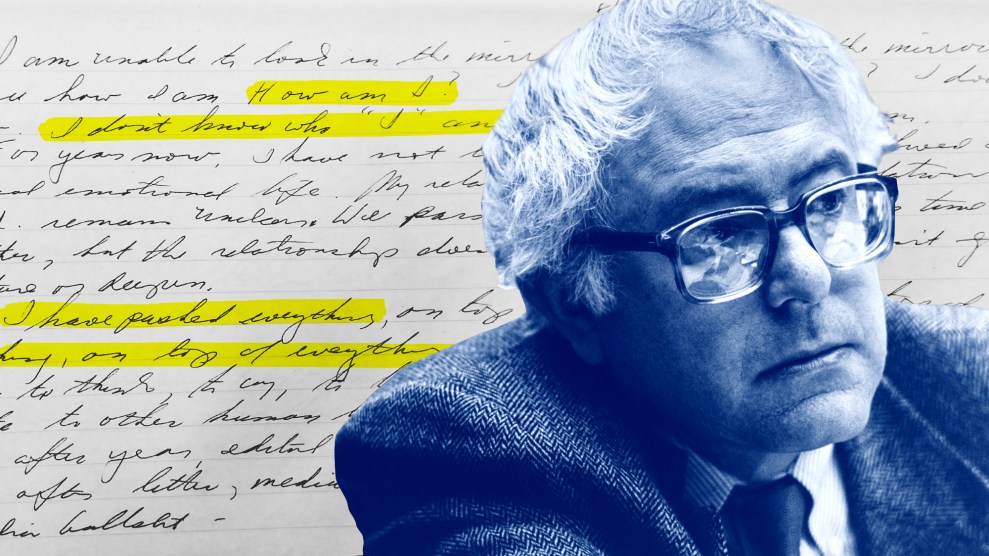

“I am unable to look in the mirror” (Text)

I am unable to look in the mirror and see how I am. How am I? I don’t know. I don’t know who “I” am.

For years now, I have not lived a normal emotional life. My relationship to J. remains unclear. We pass time together, but the relationship doesn’t grow mature or deepen.

I have pushed everything, on top of everything, on top of everything. My ability to think, to cry, to laugh, and/or to relate to other human beings is short.

Year after year, editorial after editorial, letter after letter, media bullshit after media bullshit.

Then the note trails off. “J.” was a reference to Jane O’Meara Driscoll, who ran the Mayor’s Youth Office and whom Sanders would marry less than three years later.

The media was a recurring villain in Sanders’ public remarks and private missives throughout his early career. During his time as mayor, he viewed the coverage of his administration and of national and international issues as emblematic of the way corporate ownership and new technology were impeding civic growth, and he sought out new avenues to circumvent the press, such as a public-access television program called Bernie Speaks. (In 1985, he even participated in a reverse press conference, under the tagline “Does the media lie?!” in which reporters fielded questions from Sanders about their jobs.)

In another memo from this period, Sanders offered a cold assessment of his own personal flaws:

It seemed to me this morning that planning and decision-making were two of the biggest weaknesses that I have. Not only do I not pay bills every month—”What, every month?”—I am unable to plan vacations or intelligent “leisure time activity.” It would be fun going white-[water] rafting or sailing down a Maine river or on a sailing trip, or traveling, etc. etc. Actually, I am better now than I used to be—but pretty poor.

Sanders believed he was trapped in a cycle of his own making.

Bad planning is having a house that is filthy and looks like shit because I don’t hire someone to clean for $15 a week. That, in turn, results in my not wanting people over—and fully enjoying the house…Poor planning is not getting the car fixed, etc.

Above a jotted timeline of Soviet history on the same page—apparently prompted by something he had read in the New York Times—he outlined three questions to think about. It was an attempt, perhaps, at organizing his future:

- Should I run for Governor?

- The major issues facing the City

- Where should we be one year from now?

These questions weighed heavily on him, and he would return to them again and again. In an undated memo written in the mid-1980s, Sanders wondered if he even had “the right not to run” for another term as mayor.

“If I stay in office what should I expect?” he wondered.

“‘The thrill'” was gone, he continued. “I’m just a struggling politician running a reasonably good government. Today is not 4 years ago.”

Sanders’ list of concerns in the memo that followed was long. He was battling, as he put it, “personal antagonisms and jealousies.” The Burlington Progressive Coalition, an independent faction that had put him in office and now controlled nearly half of the city council seats, was beginning to fray. His Neighborhood Planning Assemblies—an experiment in hyper-local governance, modeled on town meetings—“have failed.” And in addition to a bad relationship with the media, “We are not relating well to working and poor people.”

Part of Sanders’ anxiety about his future may have been due to his finances. Though his recent bestselling books have made him a millionaire, he spent his twenties and thirties barely making ends meet. Before becoming mayor, he had been a freelance writer and had run an educational film company out of his car. Getting elected to public office meant the first steady paycheck of his adult life. As a divorced dad with a job that wouldn’t last forever, money was still tight, and his son, Levi, would soon be heading off to college. Included among Sanders’ papers at the University of Vermont are bank statements, an overdue gas bill, and a letter from an acquaintance asking Sanders to pay back $250 he had borrowed seven years earlier.

In a 1986 memo, he again wondered about the future:

I) Psychologically — What’s going on?

A) I am not looking toward the future. There are no goals, plans to meet those goals, realistic expectations.

1. can’t get started on gubernatorial campaign.

2. am not dealing with L’s [Levi’s] present or future

3. am not maintaining the house well

4. am not traveling

5. am not planning what happens if I am out of office in a year. What do I do. What do I want to do.

II) Life goes by fast so fast. The last five years vicissitude of the last 5 years—plus my normal insanity—place me in an uncomfortable position.

Sanders’ eight years as mayor of Vermont’s largest city remain the only period of his life in which he has been the person in charge. The memos depict an uneasiness at the adjustment—going from a protest candidate to an executive tasked with keeping the streets plowed—and a series of growing pains for an unlikely leader struggling to wield power.

Image credit, from left: University of Vermont Special Collections; CQ Archive/Getty