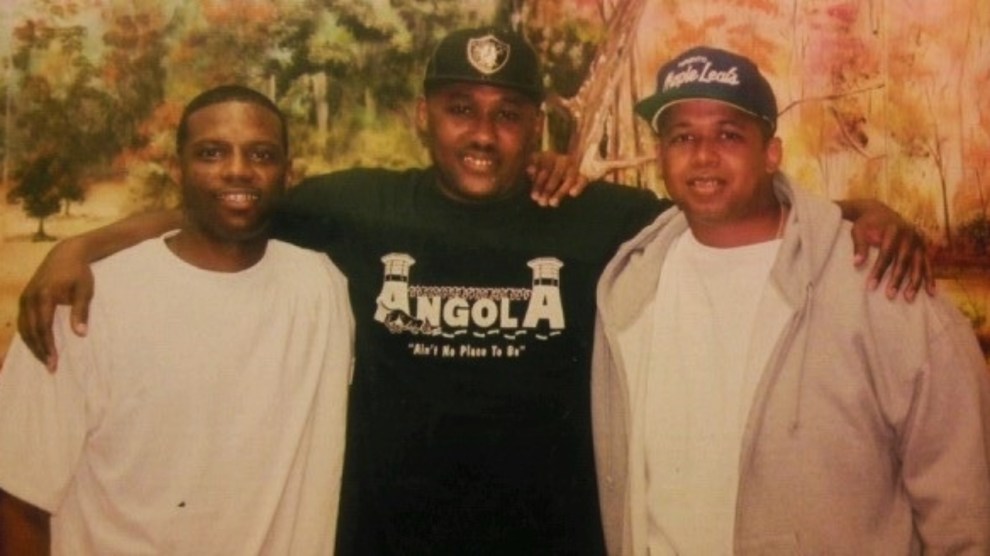

William C. Snowden, director of Vera Institute's New Orleans office, speaks about jury dutyCourtesy of William C. Snowden

A year or so after he passed the California state bar, James Binnall received a jury summons. In a San Diego courthouse, he watched Rob Lowe explain the value of his public service on a television, and then was handed a questionnaire. “It was question number seven,” Binnall recalls. “Have you been convicted of a felony?” Just the week before, Binnall had been second chair on a death penalty trial in the same courthouse. No one asked him the question then. But now, like all other Californians who’d answered “yes” to question seven, he approached a clerk in the back of the room and was told he couldn’t serve on a jury. He explained he was an attorney, that he’d even used the special entrance for lawyers to enter the courthouse that day, that it didn’t make sense.

“Write your Congressman,” the clerk responded. Instead, he spent the better part of a decade developing a well-sourced rebuke. Now a law professor at California State Long Beach, Binnall is the leading researcher on felons’ exclusion from juries. “That started it all for me,” Binnall tells Mother Jones.

As presidential candidates debate restoring voting rights to incarcerated individuals and states roll back felony disenfranchisement, Binnall is among a growing group of scholars and advocates who are examining what he calls the “next movement” of felons’ rights: jury duty.

An estimated 19.8 million people in the United States have a felony conviction and are therefore excluded from serving on juries in federal courts, as well as courts in 27 states. Several other states technically allow felons to serve on juries, but the right is contingent upon factors like parole, time of release, and approval from the prison system. Only one state, Maine, has no law regarding the matter.

Binnall says opposition tends to be two-pronged, and it harks back to the original case law to exclude felons: they “lack character” and “harbor an inherent bias” against prosecution. But that “bias,” Binnall argues, is also valuable knowledge of the criminal justice system. “There is this kind of misconception that formerly incarcerated people would get on a jury, and they’d automatically vote not guilty,” says William C. Snowden, director of the New Orleans office of the Vera Institute of Justice and head of the Juror Project. “It’s not true.”

In fact, it’s just the opposite. A recent study from Binnall mixed felons and non-felons on mock juries and found that there was not much difference between the two groups. Overall, convicted felons outperformed their non-felon peers: Felons were more likely to introduce new facts, participate for a greater amount of time. They also were equally likely to convict. “They were taking their time to try to decipher case facts,” Binnall explains. “They were cooperating with other felons and non-felons to clarify key facts and points of law. Frankly, you know, they were good jurors.”

For those with felony convictions, jury duty can feel humanizing, a path back into society. Binnall was surprised by how much felons appreciated the civil service so many of us avoid in a field study felons described feeling “segregated from everybody else”, “lower,” and “not human” on a day-to-day basis. But “when I was called to serve on a jury trial,” explained one, “it’s more like, ‘Oh, yeah. I’m part of society.'”

“You feel as though the state is welcoming you back into the fold and has corroborated the reformation,” Binnall says.

Some states are reconsidering their laws that ban felons from the jury box.

The New York Senate recently passed a bill to allow felons to serve on juries, and California is considering similar legislation. In Louisiana, on the heels of a hard-won fight to require unanimous decisions from the jury box, a bill to allow felons who have been out of prison and off probation and parole for at least five years to receive summons just failed to pass the state House.

The measures garner intense opposition. John Flanagan, New York’s Republican Senate Minority Leader, called the bill “justice denied to all law-abiding citizens” and claimed it would allow a “terrorist” to be on a jury. California is on its second attempt to pass the bill—an earlier attempt died in 2018, after Democrats, as a Los Angeles Times editorial put it, were too “concerned with currying favor with law enforcement and prosecutorial groups.”

In Lousiana, a lawmaker argued: “They were criminals, they got convicted, they went to jail…[T]here are consequences.” Snowden disagrees, in part, because felons have already served their sentence. “They’re continuing to scrap around these ideas about how to disenfranchise these folks,” Snowden said, “because they know when these folks have access to power, they have access to change.”

Snowden says another benefit to including felons is that it could help diversify juries. All-white juries have long been a problem in the American criminal justice system, in part, Snowden says, because many jurisdictions use voter registration and DMV records to call people for jury duty, excluding many residents of color. Voir dire, a legal process that allows judges and attorneys, to eliminate certain jurors from the pool after a series of questions—has historically led to black jurors excused at a higher rate than whites.

“But it’s not just a diversity of race, it’s also a diversity of ideologies,” explains Snowden. For example, someone who believes addiction is a “health problem and not a crime problem” may not want to convict someone on a drug offense and therefore could be excluded from a jury. “If that type of person lives in your community, why can’t you have them sit in judgment of your case?” he asks.

One of the biggest challenges facing the effort to allow felons on juries is that few conceive of jury duty as having weighty civil importance. “We learn about military duty, we learn about voting. Unfortunately, conversations around jury duty as an important duty get left to the wayside,” Snowden says.”We should be concerned as a community to restore all the necessary rights for that person to move on with their lives, because that is something that is very frightening to certain individuals who have been very comfortable sitting on their thrones of power—that now there’s actually some more equity in the game, particularly for individuals who have been incarcerated.”

Snowden is something of an evangelist when it comes to jury duty. He organizes workshops at “churches, neighborhood associations, Rotary Clubs, barbershops, high schools, and law schools” across the South that discuss jury duty as essential to criminal justice reform.

“I’m just one of these weird individuals that loves jury duty—loves the concept of jury duty, loves the idea of jury, loves the democracy behind jury duty,” he admits. During one of his workshops in St. Louis, he remembers a woman who was startled by the implications of inequality in the jury pool. “You just completely opened up an avenue of advocacy for me,” she told him afterward.

“When people understand that there’s actually some processes in place to prevent certain voices from accessing that jury deliberation room—that gets them motivated.”

The realization that “you don’t have to be a lawyer, you don’t have to be a judge, you don’t have to be a governor, you don’t have to be a legislator to help ensure somebody gets a fair trial” is a powerful one, he says.