Sixty-five years ago today, Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren declared that “the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place” in America’s public schools. Segregated schools were unconstitutional. Gone were the “inherently unequal” all-black schools and all-white schools. Or so we thought.

Below are photos from the Brown v. Board of Education era, but don’t mistake them for artifacts of a bygone time. The “growth of racial and economic segregation that began then has now continued for nearly three decades, placing the promise of Brown at grave risk,” researchers wrote in a recent UCLA Civil Rights Project report.

Brown may have dismantled the formal barriers between white and black students, but it has failed in its broader mission to integrate public schools.

The triumphal version of the Brown story tends to obscure the ways that school segregation has persisted, mutated, changed its name so as to slip by unnoticed. In the early years following the decision, white communities in the South resisted desegregation efforts. Prince Edward County in Virginia, the site of one of the five lawsuits that made up the Brown case, shut down its public schools to avoid integration. Private schools known as segregation academies popped up throughout the South. In Northern cities and beyond, de facto segregation raged on for years, as communities in Boston and elsewhere fought back against court-ordered desegregation efforts. It wasn’t until after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the subsequent Supreme Court decisions in the late 1960s and 1970s that the pace of desegregation sped up. Thanks to strong federal enforcement, progress, at last, could be made.

But that wouldn’t last. The Nixon administration rolled back federal enforcement of school desegregation efforts, and a series of key Supreme Court decisions, including a 2007 decision to toss out voluntary desegregation plans that took children’s race into account, limited the power of those orders. Courts released school districts from longstanding desegregation orders, ushering in an era of resegregation without the same sort of judicial and federal oversight seen after Brown.

On the 40th anniversary of the famous Supreme Court decision that effectively struck down the separation of kids by race in America’s schools, Linda Brown said she felt “disheartened” that the nation still talked about school segregation. As a third-grader, Brown had sought to enroll at Sumner School in Topeka; she was denied, setting off the legal fight that culminated in the Supreme Court case. “But the struggle has to continue,” Brown told the Washington Post in 1994. She died in March 2018, having lived long enough to see the cause evoked by her name become urgent anew.

Nine-year-old student Linda Brown (first desk in second row from right) sits with her classmates at the racially segregated Monroe Elementary School, Topeka, Kansas, 1953. When her enrollment at a ‘whites-only’ school was blocked, her family initiated the landmark Civil Rights lawsuit ‘Brown V. Board of Education,’ that led to the beginning of integration in the US education system.

Carl Iwasaki/Life Images Collection/Getty

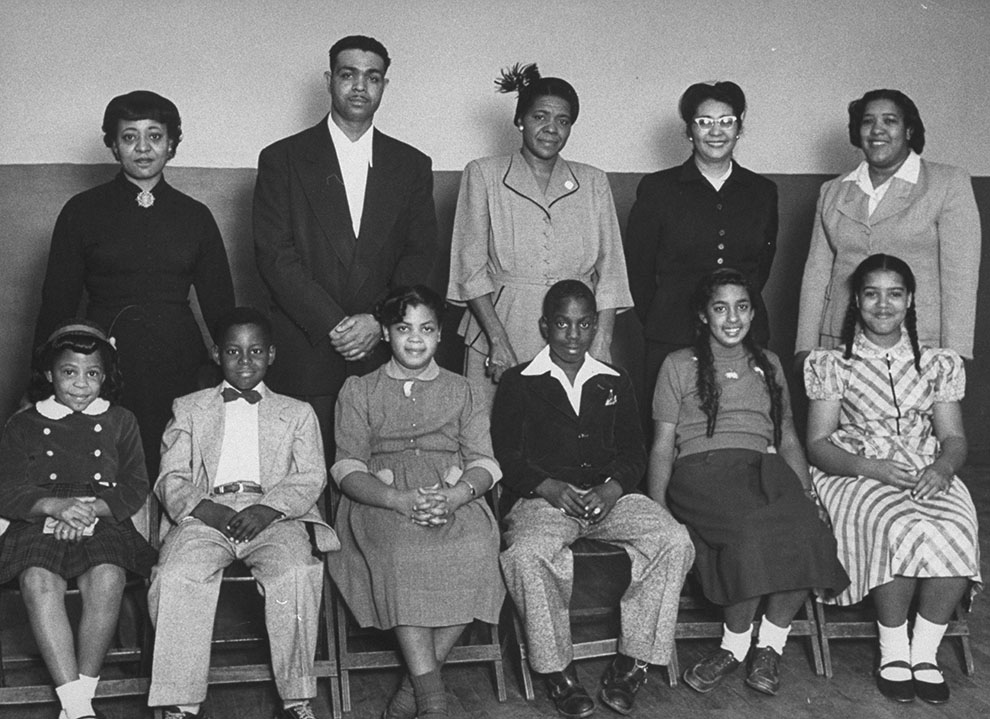

Portrait of the African-American students for whom the famous Brown vs Board of Education case was brought and their parents: (front row L-R) Vicki Henderson, Donald Henderson, Linda Brown, James Emanuel, Nancy Todd, and Katherine Carper; (back row L-R) Zelma Henderson, Oliver Brown, Sadie Emanuel, Lucinda Todd, & Lena Carper, Topeka, Kansas, 1953.

Carl Iwasaki/Life Images Collection/Getty

John Davis (left) and Thurgood Marshall argued for and against (respectively) school segregation before the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall’s arguments succeeded, and he went on to become a Supreme Court Justice.

Bettmann Archive/Getty

Group portrait of some of the more than 100 students named in the legal case ‘Dorothy Davis, et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia,’ a lawsuit filed to seek, initially, repairs for Robert Moton High School, a segregated school in Farmville, Virginia, March 1953. The case was later, on appeal, attached to the landmark ‘Brown vs Board of Education’ case. Among those pictured is Dorothy E. Davis (center, with glasses), for whom the suit was named.

Hank Walker/LIFE Picture Collection/Getty

George E.C. Hayes, left, Thurgood Marshall, center, and James M. Nabrit join hands as they pose outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., May 17, 1954. The three lawyers led the fight for abolition of segregation in public schools before the Supreme Court, which ruled that segregation is unconstitutional.

AP

Violence broke out in Baltimore as an estimated 2,000 white students stayed away from eight schools in protest against the end of segregation in the City’s public schools. As black students came out of Southern High School at the end of classes, white students jeered at and struck them. Police and teachers helped escort the black students away from the school. Here, white students gather around a police car which was used to escort the black students home. At right students hold up a sign: “Negroes are OK in their own place but not in Southern.”

Bettmann Archive/Getty

After unrest flared in December 1956, members of the ”Clinton 12” were escorted for their own protection down Broad Street to Clinton High School. The students are, from left, Regina Turner, Gail Epps, Minnie Ann Dickey, Alvah McSwain, and Maurice Soles. Clinton High School was one of the first schools forced to integrated after the Brown decision.

Knoxville News Sentinel/ZUMA

Rally at state capitol in Little Rock, 1959 protesting the admission of the “Little Rock Nine” to Central High School.

John T. Bledsoe/Library of Congress

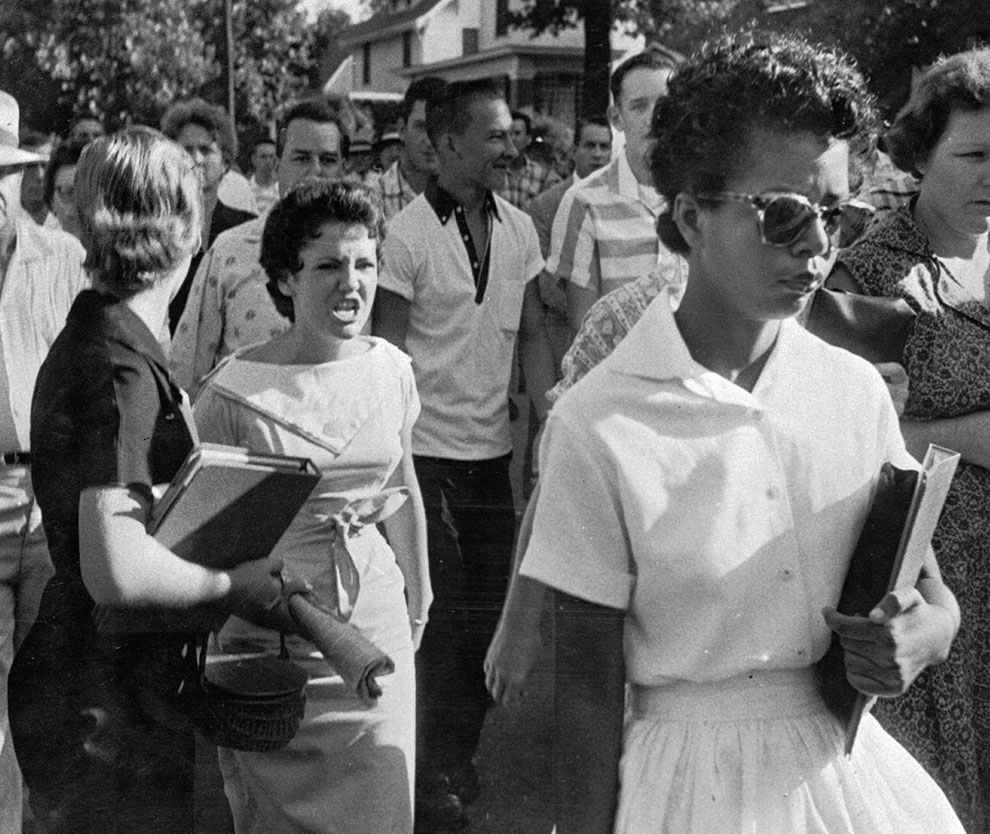

Students of Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., including Hazel Bryan, shout insults at Elizabeth Eckford in 1957 as she calmly walks toward a line of National Guardsmen. The Guardsmen blocked the main entrance and would not let her enter.

Will Counts/AP

Thurgood Marshall, attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), is interviewed outside the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C., Sept. 12, 1958. The high tribunal ruled unanimously for immediate resumption of integration at Little Rock’s Central High School. Marshall argued against any delay in presenting his case before the court. This ruling by the Supreme Court affirmed that the Brown ruling applied to schools in every state.

AP

Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace stands in the “school house door” confronting National Guard Brig. Gen. Henry Graham at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa June 11, 1963 in a symbolic effort to block integration of the institution.

AP

#