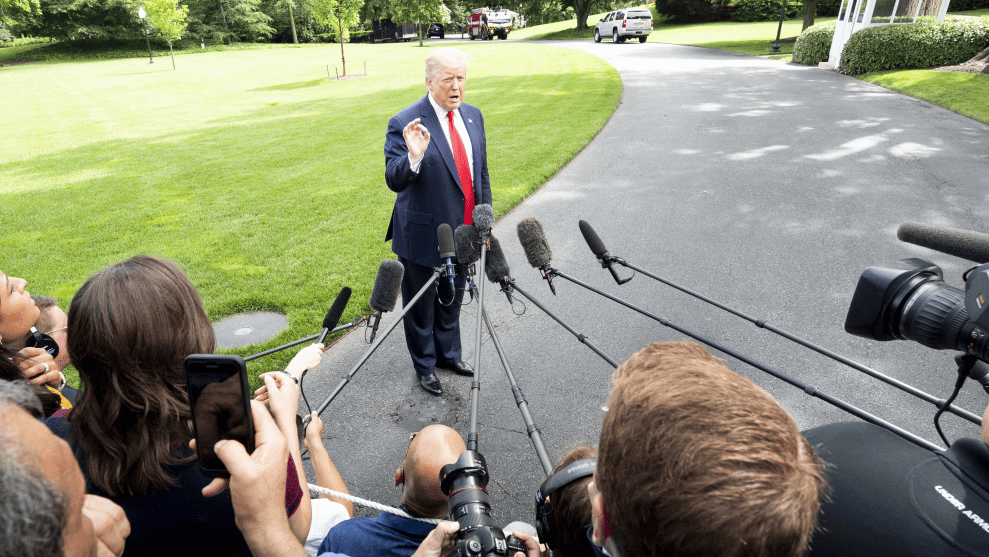

Michael Brochstein/ZUMA

Faced with yet another credible allegation of sexual assault, President Donald Trump on Monday employed a familiar strategy. “Number one, she’s not my type,” Trump told The Hill, the second time he has denied writer E. Jean Carroll’s stunning claims that the president more than twenty years ago raped her inside the dressing rooms of Bergdorf Goodman. “Number two, it never happened. It never happened, OK?”

The insinuation was as clear as it was cruel: Carroll, in Trump’s current telling, was too unattractive and therefore he would not have assaulted her. It’s far from the first time Trump has attempted to discredit his accusers by insulting their physical appearances—and in this instance, one could almost be forgiven for not knowing what exactly Trump was vehemently denying this time.

That’s because two and a half years after the bombshell recording that captured Trump bragging about forcibly touching women without their consent, Carroll’s explosive allegations, recounted in heartbreaking details in New York on Friday, are apparently no longer front-page fodder.

When media observers over the weekend questioned why the story was barely registering with the country’s leading newspapers, the Times’ executive editor Dean Baquet offered one disheartening explanation: Carroll’s original story belonged to the pages of New York, not the Times, and therefore editors relegated it to the paper’s Books section. Baquet admitted that critics accusing the paper of downplaying Carroll’s claims were right; the story “should’ve compelled us to play it bigger,” he said.

But the Times’ decision to prioritize its own investigations, even when the president of the United States is faced with a serious rape allegation, speaks to a larger numbing, one that has grown accustomed to Trump escaping accountability in relentless form: the Russia investigation, the unspeakable cruelty playing out at the border, the continued stonewalling of Congress.

And in the case of Carroll, he’s all but guaranteed to dodge responsibility, once again. As Mother Jones explained:

MJ: Today, there’s no statute of limitations for first-degree rape in New York. But that’s only been the case since 2006. Before then, New York’s statute of limitations for first-degree rape was only five years. Which laws apply, the current ones or the laws at the time?

RC: The Supreme Court case is called Stogner vs. California. Basically what it says is you cannot change the statute of limitations, and then charge somebody under it retroactively. So if a crime is committed in 1995, and the statute of limitations at the time of the crime is five years, then even if the statute of limitations is changed 10 or 15 or 20 years later, a person who committed that crime in 1995 cannot be charged under it. The person has to be charged under the law as it existed at the time.

MJ: So if the allegations are true, the president gets away with it?

RC: Correct.

With the laws governing the statute of limitations protecting him, Trump is keenly aware that he can get away with saying just about anything about his accusers. “Believe me, she would not be my first choice,” he once said of Jessica Leeds after she revealed to the New York Times that Trump grabbed her breasts and tried to push his hand up her skirt on a flight in the 1980s.

“Look at her…Tell me what you think. I don’t think so,” Trump said of the journalist Natasha Stoynoff after she too came forward to the Times with allegations that Trump pushed her against a wall and forcibly kissed her during a 2005 reporting trip to Mar-a-Lago.

“I can’t believe that he’s in the White House and it makes me sick,” Carroll said during an appearance on CNN, one of only two cable news programs to feature her since New York published her account on Friday. “What else can I do but just tell my story?” Perhaps, the media can help by ensuring that none of this fades into a reflexive black hole, even if Carroll is the 22nd woman to credibly accuse the president of sexual misconduct. Such editorial decisions could be the make or break in turning that tally into a 2020 rallying call, even if it didn’t work the first time.