The children were being sodomized in secret underground tunnels. Their captors drank blood in front of them and staged satanic ritual sacrifices. Sometimes the kids were filmed for pornographic purposes. In total, some several hundred children were subjected to this treatment. And it all happened in the middle of a safe neighborhood where crimes were not supposed to happen, let alone such unspeakable and horrific ones.

Not that anyone else witnessed the abuse. Nor was there any clear evidence that it was actually happening. But people were sure it was real. It made too much sense, they all agreed. “Everything fell into place,” one of them said. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of otherwise normal, relatively well-adjusted Americans truly believed that a massive ring of occultist pedophiles was operating right under everyone’s noses.

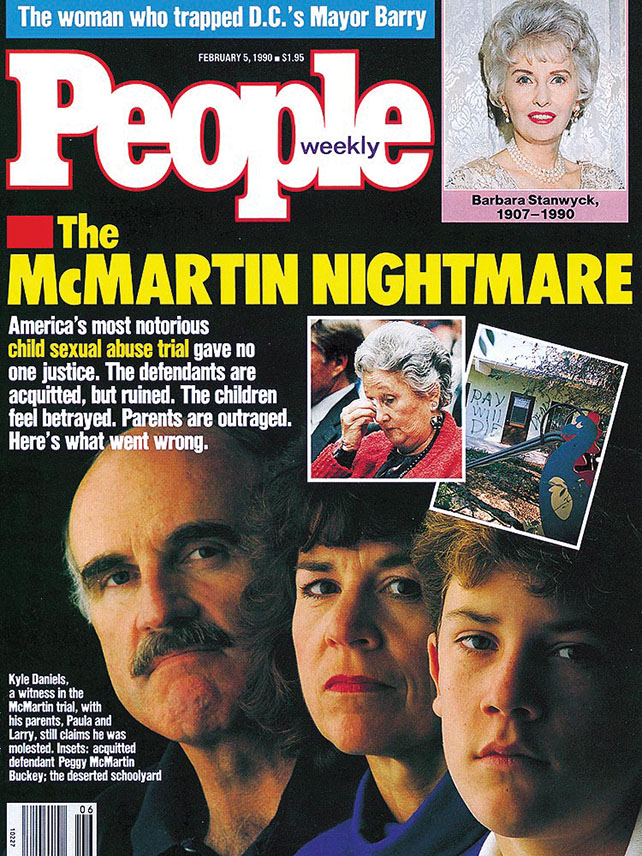

The McMartin preschool scandal of the 1980s was a sort of analog version of the more recent Pizzagate, part of a lurid and misbegotten moral panic about subterranean child abuse. Even though the supposed crimes unfolded thousands of miles and several decades apart, under very different circumstances, the two conspiracy theories share the same rough contours. The McMartin saga, which began in 1983 with accusations made by one boy’s mother, came to encompass fantastical claims about a massive pedophile ring lurking beneath a preschool in Manhattan Beach, California. Pizzagate was concocted during the 2016 presidential campaign and alleged that prominent figures in the Democratic Party were running a child sex ring in tunnels beneath the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria in a residential Washington, DC, neighborhood. Both spun off into new theories: Amid a full-on national hysteria, McMartin spawned a series of day-care conspiracies, while Pizzagate has led to QAnon, an even wilder conspiracy theory that postulates that President Donald Trump is on the verge of arresting a throng of liberal elites for facilitating and participating in a sprawling child sex ring. Both drew on natural fears about child safety and supercharged them into national phenomena with real-world ramifications. Both of course were fictions.

Conspiracies centering on the vulnerability of children are neither new nor distinctly American. Wild claims of Jews killing Christian children and using their blood in rituals—the “blood libel”—date back to at least the 12th century and have popped up every so often since then, and long before that Christians were suspected of performing similar rites. “Hurting children is one of the worst things you can say someone is doing. It’s an easy way to demonize your enemy,” says Kathryn Olmsted, a professor of history at the University of California-Davis, who has studied conspiracy theories.

Why do child-abuse conspiracies explode into public consciousness at certain moments? Explanations offered for the peculiar resonance of Pizzagate and QAnon tend to focus on pathologies in the media ecosystem—epistemic bubbles, polarization, the unruly growth of social media. But years before the fracturing of mass culture and the dawn of Reddit and 4chan, the McMartin accusations fed a national spectacle during which scores of people were wrongly accused of sex crimes against children.

The continuities between the McMartin case and Pizzagate suggest a broader explanation for pedophile conspiracies: They aren’t the residue of malfunctions in our media culture. They’re an outgrowth of the normal workings of reactionary politics.

Author Richard Beck, in We Believe the Children: A Moral Panic in the 1980s, locates the roots of the McMartin conspiracy theory in the social progress of the previous decade—particularly in the gains won by women. “In the ’80s you had a strong, vicious anti-feminist backlash that helped conspiracies take hold,” Beck tells me. “In the ’70s, middle- and upper-middle-class women had started to enter the full-time workforce instead of being homemakers.” This was the dawn of what the economist Claudia Goldin has termed “the quiet revolution.” Thanks in part to expanding reproductive freedom, career horizons had widened sufficiently by the end of the 1970s for women to become, in Goldin’s words, “active participants who bargain somewhat effectively in the household and the labor market.” They were now forming their identities outside the context of the family and household.

The patriarchal family was under siege, as conservatives saw it, and day-care centers had become the physical representation of the social forces bedeviling them. “You had this Reagan-driven conservative resurgence,” Beck says, “and day care was seen as at least suspicious, if not an actively maligned force of feminism.”

Day care held a prominent place in right-wing demonology. As far back as the 1960s, conservatives were warning darkly that child care “was a communist plot to destroy the traditional family,” as sociologist Jill Quadagno writes in The Color of Welfare. In 1971, President Richard Nixon vetoed the Comprehensive Child Development Act, which would’ve established a national day-care system. In his veto message, Nixon used the Red-baiting language urged upon him by his special assistant, Pat Buchanan, saying the program would’ve committed “the vast moral authority of the national government to the side of communal approaches to child-rearing against the family-centered approach.” In a decade of rising divorce rates, at least conspiracism and reactionary social conservatism could enjoy a happy marriage. By the time Judy Johnson came forward in 1983 with allegations that a teacher at the McMartin preschool had molested her child, the country had been primed to assume the worst by more than a decade of child-care fearmongering.

Certainly it wasn’t just the movement of women into the workplace that created the conditions for a reactionary panic. There were other cultural forces at work. The anti-rape campaign of the 1970s, historian Philip Jenkins writes in Moral Panic, had “formulated the concepts and vocabulary that would become integral to child-protection ideology,” in particular a “refusal to disbelieve” victims. The repressed-memory movement of that era had created a therapeutic consensus surrounding kids’ claims of molestation: “Be willing to believe the unbelievable,” as the self-help book The Courage to Heal put it. “Believe the survivor…No one fantasizes abuse.” And the anti-cult movement of the late 1970s had raised the specter of satanic cabals engaging in human sacrifice and other sinister behavior.

Beck likens conspiracy theories to parables. The ones that stick are those that most effectively validate a group’s anxieties, with blame assigned to outsiders. In a 2017 paper on Pizzagate and pedophile conspiracies, psychology professor Jim Kline, now at Northern Marianas College, argues that conspiracy theories “are born during times of turmoil and uncertainty.” In an interview, Kline goes further: “Social turmoil can overwhelm critical thinking. It makes us get beyond what is logically possible. We go into this state of hysteria and we let that overwhelm ourselves.”

The McMartin accusations were a vivid demonstration of the rot in the American social structure, as perceived by conservatives. Perhaps inevitably, the claims metastasized. Now it was hundreds of children who had been assaulted and subjected to satanic rituals, and now, instead of just one McMartin teacher, there was an entire sex ring involved. One boy told of adults in masks and black robes dancing and moaning; of live rabbits chopped to bits by candlelight. “California’s Nightmare Nursery,” People magazine called it. But soon the case began to fall apart. The stories of abuse turned out to have been coaxed out of children by way of dubious and leading questioning. Judy Johnson, who made the initial accusations that her son had been molested, was found to be a paranoid schizophrenic. In 1986, a district attorney dropped charges—at one point there had been 208 counts in all—against all but two of the original defendants. A pair of trials ended in 1990 with the juries deadlocking on some charges and acquitting on the others. After seven years and $15 million in prosecution costs, the remaining charges were dropped.

However flimsy its premises, the case whipped up a national panic. In 1985, a teacher’s aide in Massachusetts was wrongly convicted of molesting 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old boys and girls; the prosecutor had told the jury that a gay man working in a day care was like a “chocoholic in a candy store.” Around that time, employees at Bronx day-care centers were arrested for allegedly sexually abusing children. Five men were sentenced before all ultimately saw their convictions overturned.

Liberals certainly participated in the hysteria—Gloria Steinem donated money to the McMartin investigation—but by and large it was a reactionary phenomenon. What drove the panic, Beck says, wasn’t just the sense that children were being harmed. “It’s that families were being harmed.”

In 2016, three decades after the McMartin trial, WikiLeaks, in cahoots with Russian hackers, published the private emails of top Hillary Clinton adviser John Podesta. In one, Podesta is invited to a fundraiser at Comet Ping Pong. Amateur internet sleuths blew it up into a conspiracy theory about a child-sex ring. The pedophiles communicated in code: “hotdog” meant “young boy”; “cheese” meant “little girl”; “sauce” meant “orgy.” The theory was easily debunked. Eventually it was abandoned by the high-profile internet figures who’d initially given it oxygen, but not before Pizzagate, as it was immediately dubbed, had spilled over into reality. In December 2016, a 28-year-old man named Edgar Maddison Welch, having driven from North Carolina to Washington, DC, fired an assault rifle inside Comet in a bid to rescue the children he thought were locked away there. No one was hurt. Welch was sentenced to four years in prison.

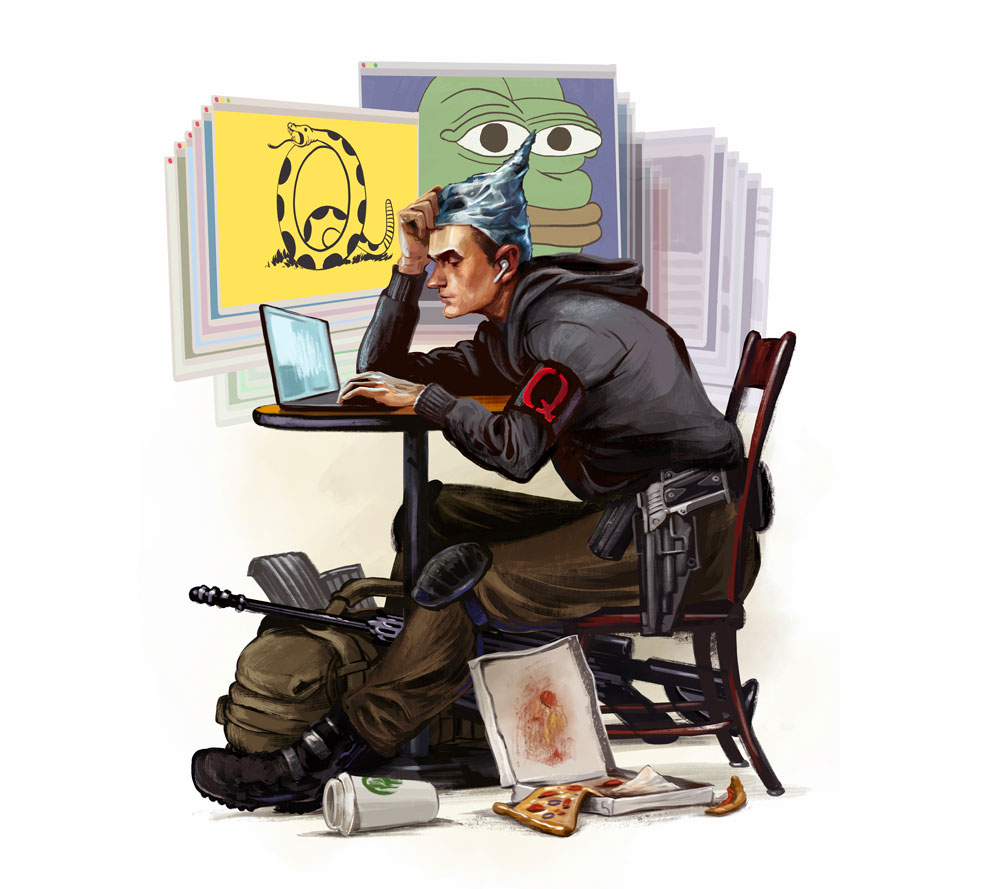

The QAnon conspiracy picked up where Pizzagate left off, alleging that the liberal elite’s pedophile ring extends way beyond one restaurant and that it is only a matter of time before Trump arrests Podesta, Clinton, and other Democratic power brokers for their crimes. All of this was fueled by an anonymous internet poster dubbed Q, who claims to be a government insider.

With Pizzagate and QAnon, the molesters have changed from day-care workers to the liberal elite, and the politics behind the theories now are more explicitly spelled out. But the general context is more or less the same: conservative retrenchment after a period of progressive social gains. If women’s entry into the workplace in the latter half of the 20th century triggered deep anxieties about the decay of traditional gender roles and the family unit, in the 21st century it was same-sex marriage, growing acceptance of transgender rights, and the seeming cultural hegemony of a social justice agenda. “Q found that fear,” says Travis View, a conspiracy theory researcher and a host of the QAnon Anonymous podcast.

“While Q directly never touches on trans rights or those sorts of things, there is a great deal of anxiety on those sorts of issues,” he says, referring to the QAnon community at large. “They’re concerned generally on the sort of acceptance of trans people and the oversexualization of children.” On the matter of transgender rights, the conspiracists are aligned with “normal” conservative politics; from the state legislatures to the White House, Republicans have made considerable hay out of attacking and overturning various protections that had been extended to trans people.

Conspiracy theories of all kinds draw their energy from social anxieties. Occasionally there is some real basis for the theories. In her book, Republic of Lies: American Conspiracy Theorists and Their Surprising Rise to Power, Anna Merlan details the belief among black New Orleanians after Hurricane Katrina that the city’s levees hadn’t failed on their own—they had been bombed intentionally to destroy the poor parts of New Orleans. The theory was “rooted in a real event—a 1927 decision to dynamite levees outside of New Orleans, the logic there being that they were going to flood low-lying areas and save the city itself,” Merlan said in an interview with Mother Jones’ Becca Andrews. “[I]t created a lingering sense of suspicion that maybe the government would do this again.”

View points out that the concern about elites preying on children isn’t baseless, either. “The core of elements of the systematic elite child abuse theories—they aren’t crazy,” he says. “There are instances of wealthy powerful abusing children and other people covering it up. Jeffrey Epstein, the Catholic Church. People have the sense that elites can commit horrifying crimes and get away with them.” The Epstein arrest earlier this month has done much to ratify the QAnon worldview. “This is just the beginning,” declared QAnoner Liz Crokin, a former gossip journalist. “The Storm is officially here.”

And thus does the legitimate concern about elite predation and impunity get woven into a demeaning and dangerous social crusade. The “Storm” cited by Crokin—also known as “The Great Awakening”—is part of the vivid eschatology that QAnon adherents share with traditional conservative culture warriors, one in which judgment is at last be rendered against liberals, and the nuclear family is restored to its proper place. “One thing they often talk about after ‘The Storm’ is that they imagine that the economy will be restored so that a single income can support a family again,” View says. “They imagine traditional gender roles and norms will be upheld and how children are raised will return to what [it] used to be.”

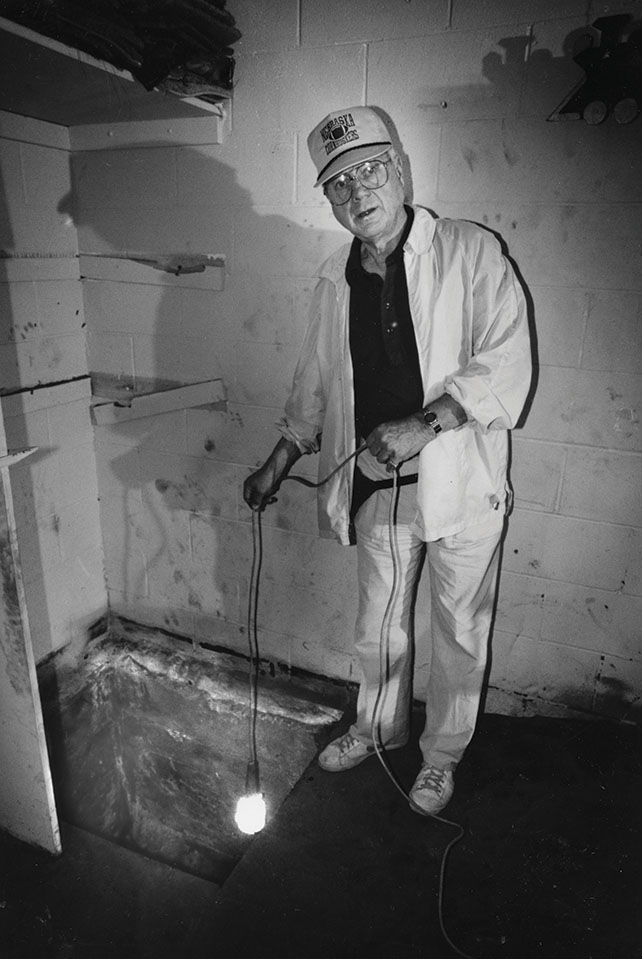

Down the rabbit hole: Private investigator Ted Gunderson shows a hole dug by parents searching for an alleged secret sex room at the McMartin preschool in Manhattan Beach, California.

Larry Davis/Los Angeles Times/Getty

The differences between the pedophile conspiracies of the 1980s and those of today are telling in their own way. There’s the matter of scale. The pedophile witch hunt of the ’80s managed to mobilize entire institutions, with much of the media uncritically amplifying its falsehoods and police taking action based on shoddy nonevidence. Lives were ruined around the country. But except for some reckless far-right pundits and websites, the media hasn’t taken the claims of Pizzagate and QAnon seriously. Earnest conversations about the conspiracies are limited to online image boards and social media.

There’s also the nature of the targets. Where the pedophile conspiracies of the 1980s attacked the institutional emblems of feminist progress, the pedophile conspiracies of the 2010s attack the cultural emblems of creeping cosmopolitanism. The ritual abuse of the 1980s supposedly happened in the suburbs in state or state-licensed institutions such as schools and child-care facilities. Today the abuse happens in businesses in cosmopolitan cities. Comet Ping Pong, in the Chevy Chase neighborhood of DC, is known as a welcoming space that regularly showcases progressive DIY artists and musicians—“a tangible emblem,” in the words of University of New Haven sociology professor Jeffrey S. Debies-Carl, “of inclusivity, tolerance, and other progressive values that are threatening to the conspiracy-prone alt-Right.”

British historian Norman Cohn, in his book Europe’s Inner Demons, finds elements of pedophile conspiracies throughout history. In the 1st century B.C., members of the Catiline conspiracy, an aristocratic plot to overthrow the Roman Republic, supposedly swore an oath over the entrails of a boy and then ate them. And in the witch hunts of the 15th–17th centuries, tens of thousands of people were tortured and killed over allegations that they’d performed ritual child murder, among other heinous acts.

The conspiracy theories documented by Cohn are fundamentally political. The rituals they describe are the means “by which a group of conspirators affirms its solidarity,” he writes, with the ultimate goal of overthrowing “an existing ruler or regime and to seize power.” The mass witch hunts that followed are political too, based on the “demonological obsessions of the intelligentsia.” The history of American political reaction is full of sex demons. Jim Crow was buttressed by myths about black male virility. Likewise, North Carolina’s infamous bathroom bill was sold in part on the fear that predatory men could say they’re transgender to gain access to women’s bathrooms. Opponents of abortion rights continue to conjure gory fantasies of promiscuous women committing “infanticide,” an incitement that Trump turned into an applause line in an April rally.

In this way, pedophile conspiracies act as a sort of propaganda of the counterrevolution, a fun-house reflection of the real threats to the social order. This is what connects QAnon and Pizzagate to McMartin to the witch hunts of the Middle Ages to the dawn of major religions. The demons may take different forms, but the conspiracy is basically the same: Our house is under attack.

“Decay of morals grows from day to day,” goes one despairing account. A secret cabal is wreaking havoc across the land, the man complains to his friend. Its members “recognize one another by secret signs and marks,” and “everywhere they introduce a kind of religion of lust” that subverts “ordinary fornication.” There is a rumor that they worship the “private parts of their director and high priest.” Maybe the rumor is false, “but such suspicions naturally attach to their secret and nocturnal rites.”

In this dialogue, written by Marcus Minucius Felix in the 2nd century, the Roman pagan Caecilius Natalis speaks of Christians the way Pizzagaters described John Podesta and his fellow liberal elite. Natalis is particularly incensed by the cult’s initiation ritual. The details are as “revolting as they are notorious”: New members are initiated into the cult, he reports, by stabbing and killing an infant who has been coated in dough.