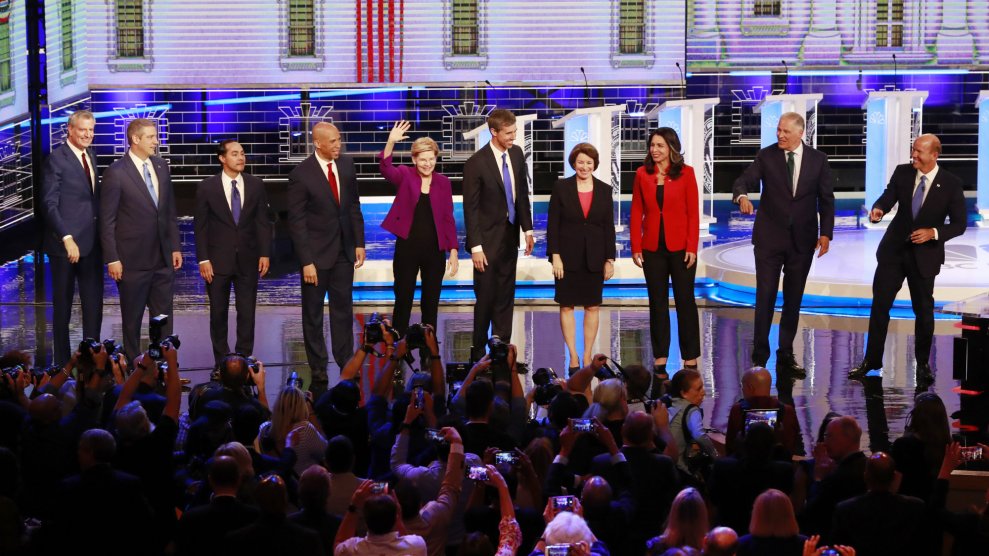

Wilfredo Lee/AP

America is in the middle of a housing crisis. There is not a single county in the US where a minimum wage worker can afford to rent a two-bedroom apartment. Every night, nearly 553,000 people sleep on the streets in the United States. So, it’s no surprise that the 2020 presidential hopefuls are trying to woo voters with plans that they say would offer a solution to this pervasive problem.

A March 2019 National Low Income Housing Coalition poll found that 85 percent of Americans believe ensuring everyone has a safe, decent, affordable place to live should be a national priority, and 80 percent believe that Congress should take major action to make housing more affordable for low-income people. But presidential leadership matters too, so 2020 Democratic candidates are weighing in.

Julian Castro, the former head of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Sens. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) and Cory Booker (D-N.J.) have championed a rental tax credit, which would reimburse taxpayers for the amount of rent they pay over 30 percent of their income. As explained by Curbed, a housing-focused online site, if 30 percent of your income is $15,000 and you pay $18,000 in rent in a year, the government will refund you $3,000. Castro has also proposed expanding housing vouchers, and Harris, Booker, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) all focused on strategies to end housing discrimination, which can be a barrier to low-income families finding affordable housing.

Housing advocates are thrilled that so many candidates are finally paying attention to this issue, which has not been the case in the past. “This is the first time low-income housing has been a visible part of the presidential campaign,” says Steve Berg, the vice president for programs and policy at the National Alliance to End Homelessness. But, how realistic are their plans? Where should a president begin in trying to address the housing crisis? And how much power does a president really have to enact meaningful reforms?

To answer these questions and more, Mother Jones spoke with Carol Galante, a professor of affordable housing and urban policy at University of California Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

Several of the candidates, like Julian Castro, Kamala Harris, and Cory Booker have proposed a rental tax credit, which would require Congress to include it in the tax code. But once it’s in, it’s pretty hard to get out. What are some of the pros and cons?

The biggest pro is that anytime you can get something done on the tax code versus through the discretionary budget—like the housing voucher program is in the discretionary budget— you can make it more of an entitlement. So, if you are eligible for it, you get it. Rental tax credits would be in the tax code until there’s a major overhaul of the Tax Act, which as we’ve seen only happens every 20 or 30 years.

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit is through the tax code and has built more affordable housing than public housing ever did, because public housing depended on the same discretionary annual appropriations. And there haven’t been any kind of new dollars for new public housing for decades.

But, getting a tax credit once a year might not help you pay your rent for the other eleven months.

We would need to get changes in the IRS system, so that you could get this refundable tax credit more often. Maybe not once a month, but maybe once a quarter. I think with technology and with some investment at the IRS, you could fix some of the challenges that people see with the timing of the money.

Can you think of any other cons besides the timing of getting a tax credit?

You have to be sure that it’s what you would call a refundable credit. People who are on fixed incomes, on public assistance or getting Social Security, they would have to file a tax return in order to get it. Perhaps that is an administrative burden on the person receiving it. But we have armies of volunteers who go out to lower income communities and do outreach once a year to get people signed up to get the Earned Income Tax Credit. And I think you would need to have a similar type of outreach effort.

Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren want to use federal funds as way to get communities to reform zoning laws that often stand in the way of building more affordable housing. Are incentives or withholding funds the right approach when the goal is to build more affordable housing? The federal government can say, “If you don’t reform your zoning laws, we won’t give you money to build homeless shelters.” But communities can respond, “Good, we didn’t want any homeless shelters anyway!”

Withholding certain kinds of funds is not necessarily the incentive, or the motivation, that communities need to do the right thing. But, I do think that financial incentives that go for the kinds of things that communities want and need—things that they’re not getting money for today or they’re having to tax their citizens through property taxes to get—are the kinds of incentives you want to have.

Is it safe to say that giving incentives is better than just withholding the funds?

Yes, I just think they need to be significant, and they need to be for the kinds of things that communities need. So, additional infrastructure dollars, and dollars for parks and recreation, education.

Castro wants to dramatically expand how many vouchers are available to the people who need it. How easy would that be to do?

It’s expensive, and it’s on the discretionary side of the budget. Think about it this way: The entire HUD budget is, what, maybe $48 billion. The existing voucher program is somewhere around $22 or 23 billion. To expand it to everyone who is eligible is going to more than double the HUD budget, and I just don’t think that is realistic out of the discretionary budget.

The one thing that has been effective in recent years is expanding the pot of vouchers for specific populations. So VASH [Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing], which is for homeless veterans, and things like that. I think that you can incrementally add some vouchers to the pot. That certainly will be helpful.

Several of the candidates have talked about wanting to tackle housing discrimination, but how much can a president really do on that?

The biggest thing I think a president can do is work with HUD on these court rulings on what discrimination is and what counts as discrimination. There are definitional issues that affect the rules that HUD makes, like the rule on what’s considered to be a “disparate impact.” So, is it discrimination if you didn’t intentionally mean to discriminate but the impact of your decision is that it is discriminating against a certain class of people, whether you’re a landlord, or whether you’re a mortgage lender? This is a whole body of legal rule-making that the president, in setting the agenda, can support.

Elizabeth Warren wants to build new housing by taxing really rich people. How much of that and some of these other ideas rely on having a Congress that actually functions?

Virtually all of these proposals would require congressional action. Again, there are some things that through agenda-setting and rule-making [the president can do]. All you have to do is look at the kinds of things that the Trump administration has tried to do with executive orders and stopping rule-making that the Obama administration was putting in place on some of these very issues. A president, even with a still stubborn Congress, could do certain things to repair some of the damage that’s being done right now. The things that require big dollars and big changes in housing policy from where we are today, those definitely require a cooperative Congress.