Congressional District 18 candidate Randy Perkins after conceding to Brian Mast during his campaign gathering in 2016. Richard Graulich/ZUMA

This story was originally published by ProPublica, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Last year, a Department of Defense contractor quietly donated half a million dollars to a group supporting President Donald Trump’s reelection.

Once a watchdog organization noticed it, the contribution raised an alarm. Federal contractors are not allowed to donate to political entities. And groups are required by law to examine all donations for potential legal issues. If they discover that a contractor has made a contribution, the money has to be returned.

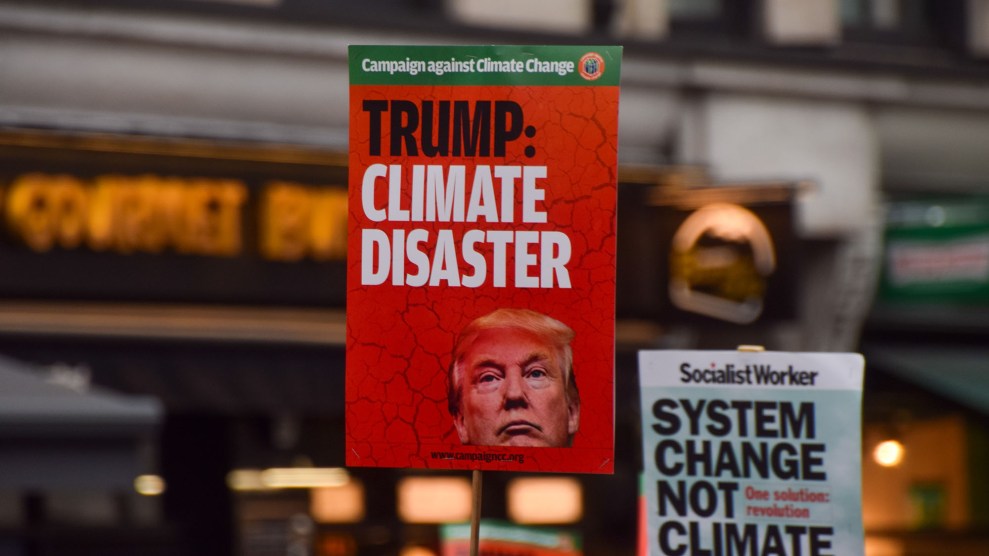

The other unusual aspect of the donation was the man behind it. Randy Perkins, the founder of DOD contractor AshBritt Environmental, had no history of six-figure contributions to federal political groups, although he has been a regular donor to Republicans for the past 15 years. He ran unsuccessfully for Congress as a Democrat in 2016.

The watchdog group pointed out that the money came in a day after AshBritt won a supplemental contract award worth $460,000 from the DOD for wildfire cleanup, bringing its contract total to about $1.7 million.

Asked about the donation, Perkins said he had meant to make a personal donation to express his support for specific Trump policies: “I actually think this administration cares deeply about children and mental health issues.” He said the contract extension had nothing to do with the contribution.

America First Action, the Trump super PAC that accepted the donation, adjusted its report on the source of the funds only after the watchdog group, the Campaign Legal Center, filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission. Since America First’s creation in 2017, it has refunded just a fraction of 1% of all the funds it has raised.

If you’ve been hearing about America First recently, it’s likely because two associates of presidential lawyer Rudy Giuliani were arrested on allegations that they illegally funneled money to the group.

But that case is not the only problem that has ensnared the PAC as its role in backing Republican candidates has grown.

In another instance, the American subsidiary of a Canadian company made three donations totaling $1.75 million to America First in 2018. In another complaint, the Campaign Legal Center questioned the source of the donation and alleged that Wheatland Tube LLC may have violated laws against foreign nationals contributing to federal campaigns. The company declined to comment on the matter.

Last year, Common Cause, the political reform group, asked the FEC to determine whether the Trump campaign had illegally coordinated with America First and America First Policies, a related group that can raise money without disclosing its donors. The complaint alleged that the president and his campaign were improperly soliciting contributions for the two entities.

The FEC has not acted on any of these complaints to date, and it currently lacks a quorum to vote on enforcement actions proposed by its staff.

“The number of complaints is pretty remarkable,” said Ann Ravel, a Democrat who served as chair of the FEC in 2015.

America First communications director Kelly Sadler told ProPublica that the group takes its obligations seriously and goes to great lengths to comply with the law.

The PAC has denied any wrongdoing in the criminal case against the Giuliani associates. Sadler said the contribution at the heart of the indictment has been placed in a segregated account and will remain there “until these matters are resolved and a court determines the proper disposition of the funds.”

As a super PAC, America First can take unlimited donations from corporations and individuals. In return, it is not supposed to coordinate with campaigns, which are restricted in the amount of donations they may accept.

America First has raised more money to support Trump’s reelection than any super PAC. It is currently chaired by Linda McMahon, and it has raised nearly $50 million over the last two years, including about $9 million in this election cycle to reelect Trump.

Its affiliated nonprofit group, America First Policies, was co-founded by Brad Parscale, now the president’s campaign manager.

McMahon, a former professional wrestling executive, until March was a member of the president’s cabinet, overseeing the Small Business Administration. She also donated $1 million to the PAC, whose public filings show 19 donations of at least $1 million.

The PAC’s top donors include casino magnate Sheldon Adelson and Geoffrey Palmer, a billionaire California developer. Richard and Elizabeth Uihlein, who run a shipping supplies company, donated half a million dollars each.

In the 2018 election, America First spent more than $29 million supporting Republican candidates in House and Senate races. Former Texas Rep. Pete Sessions, a powerful GOP leader, received heavy backing from the PAC—$3 million toward a contest he would go on to lose.

The $500,000 donation attributed to AshBritt was among a flood of big donations coming into the PAC in the spring of 2018. The company, based in Deerfield Beach, Florida, does disaster cleanup work.

The Campaign Legal Center’s complaint got little attention. Under FEC rules, a committee has 30 days to confirm the legality of a questionable donation or to refund it; nearly three months passed before the PAC amended its filing to show the donation as being made directly by Perkins.

Perkins said he tried to rectify the matter by providing “all paperwork to the FEC” and resubmitting forms to America First stating that the funds were in fact drawn from a corporate account that would later be taxed as personal income.

“When I wrote the check, I cleared it with America First,” Perkins told ProPublica.

Perkins acknowledges that the optics of his America First donation are less than ideal.

“The facts might be a problem,” he said. “But they are facts.”

A few weeks after Perkins’ donation, the PAC received $325,000 from Global Energy Producers, the Florida energy company that is now at the center of a presidential impeachment inquiry. The PAC was referred to as “Committee 1” in the federal indictment of Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman.

The two men, according to the indictment, were key characters in a coercion campaign to recall the United States ambassador to Ukraine, Marie L. Yovanovitch, which they believed would pave the way for an investigation into Trump’s Democratic rival, former Vice President Joe Biden, and his son Hunter.

The indictment also alleges that Fruman and Parnas promised to fundraise for Sessions. Around the same time, Sessions wrote to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urging Yovanovitch’s ouster.

Sessions, who is now running for Congress in a new district, did not respond to messages from ProPublica. In a statement issued on his behalf, he acknowledged meeting with the two Florida businessmen several times but said he took no action on their behalf.

Sessions denied that his letter to Pompeo was directly related to the meetings. He said he will donate the contributions Parnas and Fruman gave to his campaign to Texas charities.