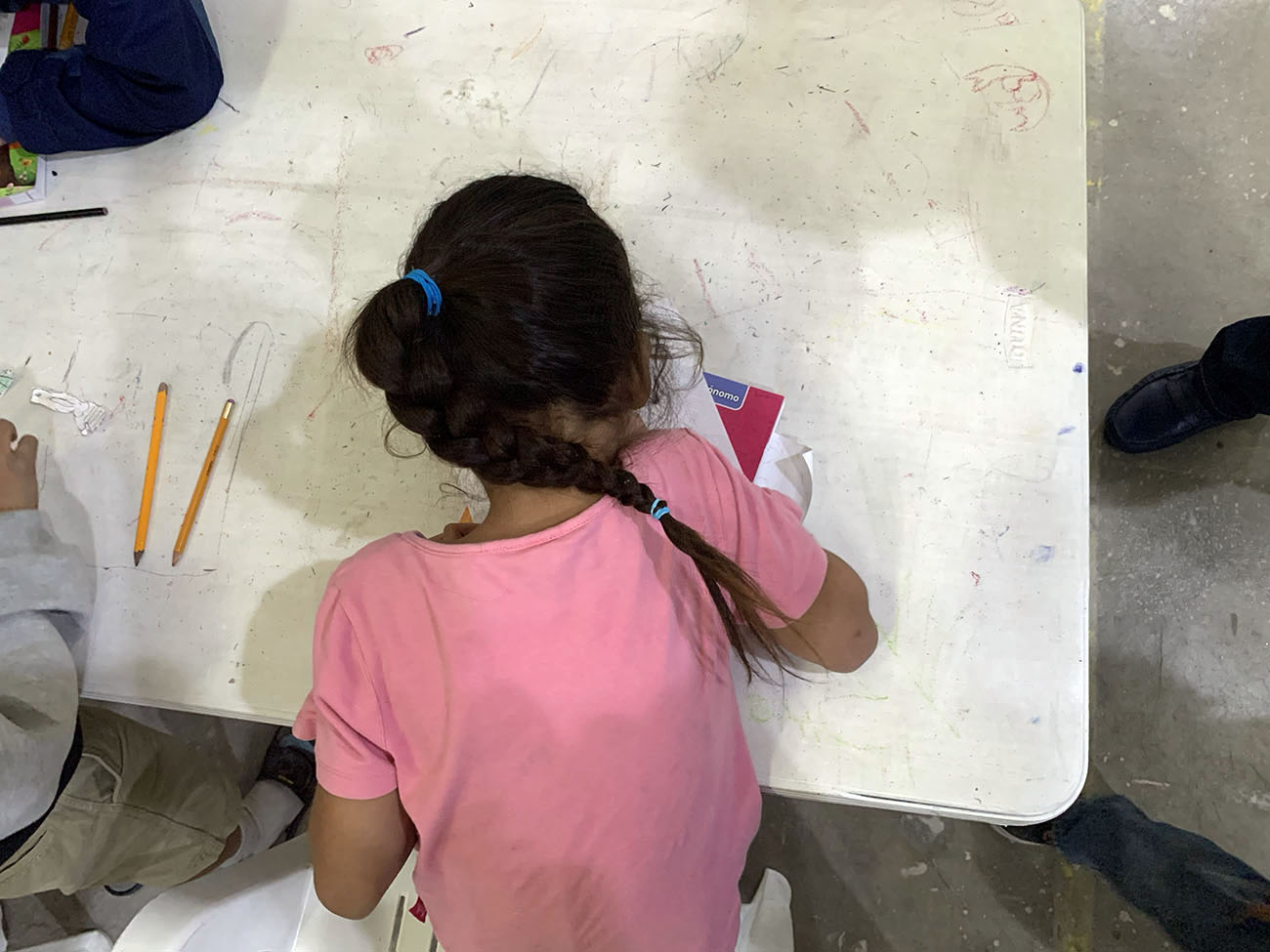

Fernanda Echavarri/Mother Jones

Four miles south of the narrow footbridge that connects Ciudad Juárez to El Paso sits a sprawling, peach-colored former factory with a new “Bienvenidos” banner above its doors. The Leona Vicario Migrant Integration Center opened four months ago as the first of several shelters run by the Mexican government to house asylum-seekers turned back at the US border. With nearly 600 Central Americans currently taking up residence inside, it is a concrete manifestation of how President Donald Trump’s immigration policies have fundamentally altered the decades-old process of seeking asylum in the United States.

The shelter opened to manage the large numbers of Central Americans who have been funneled through the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols program, or “Remain in Mexico.” Under MPP, asylum seekers are forced to stay in Mexican border cities for the duration of their asylum proceedings—a process that can take months or years. Since MPP was implemented in late January, more than 50,000 people have been sent back to wait in Mexico.

In January, after the Trump administration announced the policy, Mexican officials called it a “unilateral move.” Over the summer, when the number of migrants reached record highs, Trump threatened Mexico with steep tariffs if it didn’t stop more migrants from reaching the US border. Mexico conceded in June. Two months later, Leona Vicario opened its doors to asylum seekers who had been sent back to Juárez. “Any expense we incur in building shelters like this one will be far less than what the tariffs would cost us,” said Mexico’s Labor Undersecretary Horacio Duarte Olivares at Leona Vicario’s opening, according to El Paso’s KTSM. “The export tariffs would devastate our country’s economy.”

Listen to reporters Fernanda Echavarri and Julia Lurie as they tour a converted factory that now holds nearly 600 Central Americans, thanks to Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, on this episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

The former maquiladora is about as homey as a factory could feel. A mural of Central American and Mexican flags is bordered by colorful handprints of the shelter’s first residents. Collages celebrating Columbus Day and whiteboards with upcoming events dot the walls. There’s a notice for a workshop on managing stress that will take place in the “children’s corner,” and a sign-up sheet for volunteers interested in putting together a Day of the Dead offering.

Inside a cavernous central room with concrete floors and cinder block walls, rows of hundreds of blue metal bunk beds extend in all directions. The sheets hint at who occupies them: dark, muted colors in the section for single men, pink flowers and Disney characters in the family area. About half of the shelter’s residents are children. Another room resembles Costco, with toilet paper, bottled water, and other sundries stacked in floor-to-ceiling shelving. In one corner, a handful of women dance Zumba to a Marc Anthony song as toddlers scamper around a makeshift nursery. In the corner of another warehouse room, more than 70 kids sit at plastic tables in an impromptu school: elementary schoolers fill in coloring books, while older kids fill out workbooks. Outside, members of the Mexican military prepare rice and pea soup for lunch in a camo food truck the size of a big rig.

“It can feed up to 3,000 people—and over there we have our tortilladora,” explained our tour guide, Abraham Mercado, who works for Mexico’s Department of Labor and Social Services, pointing to a second food truck that churns out fresh tortillas.

Leona Vicario feels a bit like a grand experiment in how to quickly house and feed thousands: Never has the Mexican government been forced to shelter US asylum seekers as it has in the last few months. “Nobody understood MPP at the beginning, and we are learning as it evolves,” said Tania Guerrero, an attorney at the Catholic Legal Immigration Network who offers legal advice to migrants in Juárez. The Mexican government is opening two more “migrant integration centers” this month— one in Tijuana this week and Mexicali at the end of the month, according to Department of Labor officials. A fourth is in the works for Nuevo Laredo.

Most migrants come to Leona Vicario after they’ve petitioned for asylum in the United States; often they were detained for a few days before being returned to Mexico with little explanation. Many are in shock, unfamiliar with Mexico and afraid of notoriously crime-ridden Juárez. Some believe that they are still in the United States.

They’re technically given two weeks to stay at Leona Vicario as they get used to life in Mexico. “That’s how long it takes us to connect them with an employer—they have enough time to collect a paycheck and be prepared to integrate,” Mercado explained, though he acknowledged that many stay a couple weeks extra as they nail down housing and job logistics. During their stay, migrants have access to medical and mental-health services and are set up with Social Security-like cards and documents that allow them to work in Mexico. Afterwards, some move into smaller, overcrowded migrant shelters in Juárez run by churches or other NGOs. Some move into their own housing. Others, confronted with the new reality at the border, give up and go home. A United Nations office set up at Leona Vicario helps arrange transportation back to their home countries.

“This is a large undertaking in a short period of time, so I try to be critical with that in consideration,” Guerrero said. Still, a two-week integration timeline is unrealistic, particularly since the process involves far more than a roof and the promise of a job: “The ideal migrant is healthy, unafraid—and that is not the migrant that is under MPP, and that is not the migrant at Leona Vicario,” she said.

Migrants are particularly vulnerable to exploitation of all kinds in Mexico, from kidnappings to wage theft. There have already been more than 340 public reports of rape, kidnapping, and other violent attacks against asylum seekers returned to Mexico under MPP, according to the advocacy group Human Rights First. Most crimes against migrants aren’t reported for fear of corrupt police; stories abound of cops in Juárez declining to investigate those that are. Visitors to Leona Vicario are met at iron gates by an armed guard.

Mercado describes himself as a “pretty tough person when it comes to emotional stuff” but admits that it’s been challenging to work at the shelter—particularly when families leave after he’s gotten to know them for a couple weeks “Here I’ve become soft,” he said. “How could you not?”