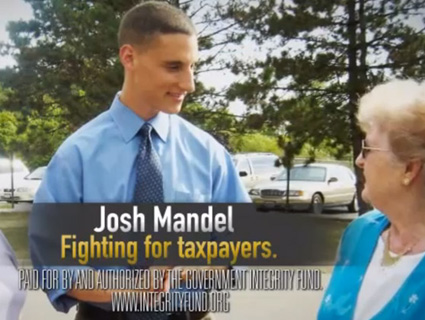

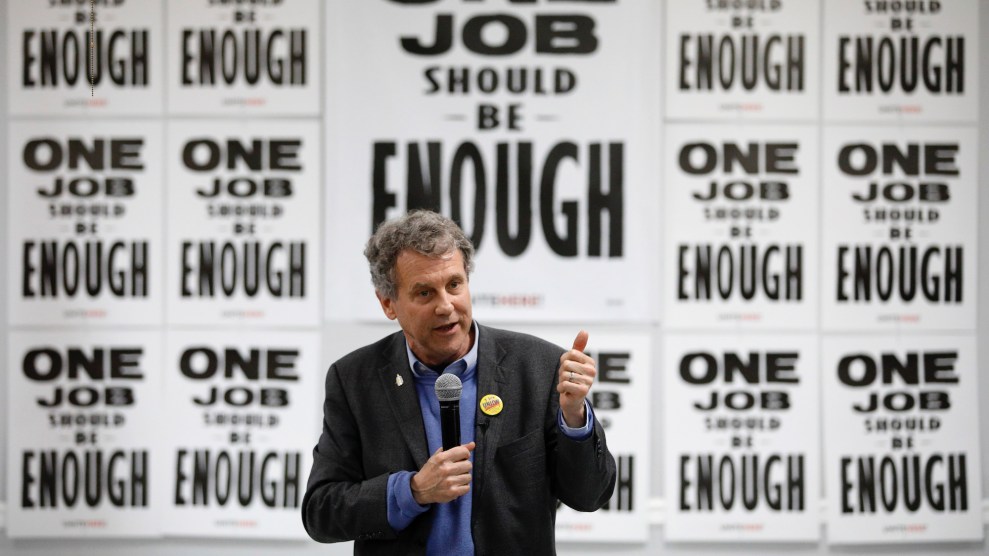

Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) speaks at a culinary union hall in Las Vegas on February 23, 2019.John Locher/AP

Sherrod Brown was going to run for president. But he wrote a book instead.

Well, not exactly, the Ohio senator protests when I say as much. “I didn’t think, ‘Well, it’s a presidential primary and we gotta beat Trump, it’s time to write this book,’” he explains, in his unmistakable voice that shares a cadence with an idling diesel engine. Brown tells me he’s been working on Desk 88, in bookstores on November 5, since the beginning of the Obama administration—a time, in his estimation, that “looked like potentially another progressive era” before Republicans retook control of the House of Representatives in 2010.

That’s the central conceit of Brown’s latest tome: American progressivism, as told through the stories of eight Democrats who have called Brown’s assigned desk on the Senate floor—you guessed it, Desk 88—their own. (In the Senate, lawmakers choose their desks from among those vacated by their predecessors; Democrats sit, counterintuitively, together on the right side of the room.) Among those profiled: Hugo Black, the Alabama senator who was once a KKK member but later upheld pivotal civil rights decisions as a member of the Supreme Court; Albert Gore Sr., the former vice president’s father, who entered the Senate as a civil rights detractor but left it a defender; and Robert F. Kennedy, brother of John F. and 1968 presidential candidate who championed anti-poverty and anti-war causes during his brief Senate tenure. “What drew me to Desk 88 was the idea that connected them: progressivism,” Brown writes. “Progressives of all generations, and certainly those who sat at Desk 88, share a revulsion at injustice and wage inequality and wealth disparity.”

Brown’s effort isn’t merely a solipsistic trivia exercise. Desk 88 presents a concise history of America’s progressive eras. In the book, Brown identifies three: the labor reforms of the turn of the 20th century, the New Deal programs under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the civil rights advances under President Lyndon B. Johnson. As he does, he observes some broader themes. Each epoch lasted only a handful of years, but their effects run long—the advances made in workers’ rights, civil rights, health care, and environmental protections have been nearly unassailable once their underlying bills were signed into law.

Does Brown think we’re in a progressive moment now? No, he says definitely, blaming the occupant of the White House and Republican leadership in the Senate for blocking the progressive agenda. But he is hopeful for the future. Brown doesn’t linger on policy prescriptions, and if he had, self-identifying “progressives” might have chafed at them: Brown does not support Medicare for All or the Green New Deal, two cornerstones of the left’s platform. Instead, Brown lays out a vision for honoring the “dignity of work,” a phrase with origins in a Martin Luther King Jr. sermon that Brown’s flirtations with the presidency injected into the 2020 Democratic primary lexicon. “If work is honored and respected, workers feel valued; and when they know our society believes in the dignity of work, and their employers believe in their dignity of work, workers are empowered as citizens,” Brown writes. “That strengthens our communities, our nation, and our democracy.”

On the eve of his book’s release, I asked him about what he learned about the progressive movement, what he thinks is wrong with the 2020 presidential primary, and how we should remember the complicated lawmakers who once sat at Brown’s desk—lawmakers who were at times complicit with racism and bigotry but advanced the progressive causes nonetheless.

Why did you decide to write this book now?

I wanted to learn more about this place I work in and I wanted to know more about progressive history. And I think you learn from looking back. There was the Progressive Era of the 1910s—in spite of Woodrow Wilson being a racist, it was a progressive era on finance and some other things, workers’ compensation, things like that. Then the 1930s, what Roosevelt and Congress did in ’33, ’34, ’35, ’36, and then in ’64, ’65, ’66. What jumped out at me was how short progressive eras are—how the reaction is fierce and furious, and how we do such big things in them that it affects people’s lives in big ways, no matter how much the right wing tries to chip away at it. I wanted to think about historic trends and how it affects our ability to fight for progressive values. And that sort of came out to me reading it that way.

Interesting that you note you started writing this in 2009 and 2010, when you thought you were on the cusp of another progressive era during the Obama presidency. Are we in a progressive moment?

We’re not in a progressive moment yet. We have a terrible Supreme Court, a worse than imaginable president, and someone who takes particular pleasure in the Senate of dumping stuff in his legislative graveyard. I don’t necessarily predict this, but I think in 2020 we very well could have the dawning of a new progressive era with a new Senate and a new president. We’ll see. But the King quotation in the book’s prologue, at the top of the page—it says, “We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability.” That’s really the call to action in any kind of any kind of movement.

So your yardstick for progressivism has to do with the laws that get passed and the programs that get enacted, not the spirit in the room?

No, it is the spirit in the room. I mean, this stuff never happens in isolation. I’m not a professional historian here, but Johnson could do all he did because the civil rights movement was really boiling up, because Kennedy was assassinated, because they’d come out of the sleepiness of the Eisenhower years because this next generation was coming up—the kids of the World War II veterans. All that came about in a sort of perfect storm to do all this.

You gotta be ready for the opportunity. And I want us to be ready in 2021. I’m already thinking, what do we do in the Banking committee, if I’m chairman in 2021, for housing? The committee is called Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, but we don’t do much housing right now, and that should be the agenda if we win the Senate and take back the White House.

Throughout the book, you cite a construct of the “Conservator” from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1841 essay The Conservative as a way of wrestling with the tensions that exist between progressive populism and those who try to hold it back. You write, “Conservators—those with privilege and wealth, who want to hold on to what they have—are vastly outnumbered,” Brown writes. “But they long ago figured out how to consolidate power: exploit the fear of people who would benefit from change by convincing them that change is too risky.” Can you tell me why that’s a helpful way to think about progressivism and movement politics?

So the Emerson construct of history’s an ongoing battle between the Conservators and Innovators. The Conservators want to hold onto their privilege and progressives want to move the country forward and give people, particularly moderate- to low-income people, an opportunity to get ahead.

I just think that everything changes and nothing changes. I guess what came through loud and clear is: The Conservators never ever give up. Powerful people—the ones that cling to their wealth and status—they lose fights, but they never want to lose the war. We won a lot of times against them. We have Medicare, workers’ comp, minimum wage laws, safe drinking water laws, better civil rights laws—all those things. We’ve won a lot, but they always try to dismantle—the Affordable Care Act is the best example.

With that construct in mind, are there any lessons that you think the 2020 field isn’t heeding as they try to recapture the White House?

Nobody’s talked about the dignity of work enough. I’ve been thinking a lot about this. There’s a story I tell in the book: I was at a Ford plant in 2000 and people were just sitting in the cafeteria—eight or 10 workers were there on break. They were all voting for Gore except one. And I said, “Why aren’t you voting for Gore? Why are you voting for Bush?” He said, “Well, Gore wants to take my gun.” And the guy sitting next to me says, ”Well, Sherrod’s got the same position on guns and you vote for him.” And he said, ”Yeah, but Brown fights for me.”

I think the most important lesson from this book and the most important lesson to me in the Midwest is you’ve got to fight for workers in their workplace and that will overcome that. That it doesn’t mean that I’ll ever get 60 percent in Appalachia again like I used to. I make up for it in greater Columbus and greater Cincinnati. But it does mean that people will listen even if they don’t like my position on guns—and I’ve held that for 30 years, 25 years. They don’t like my position on marriage equality—I came out more than 20 years ago for it. They don’t like that I’m pro-choice. They may not like those things, but if they know I’m fighting for them in their workplace, we will get enough of their votes to win. The workplace isn’t just union steelworkers. It’s hospital workers, it’s people that prepare the food in the cafeteria, it’s people who clean offices. It’s the way to talk about the dignity of work. You look at the world, as you campaign, through the eyes of workers, and you look at the world, as you govern, through the eyes of workers.

It’s not like “dignity of work” hasn’t come up. One of the Democratic candidates has said the phrase in almost every debate. Do you think the message isn’t coming through?

I don’t think anybody’s doing it enough. I mean, I’m not in the arena so I don’t have much room to talk. I just know any number of these candidates can win the industrial Midwest if they really focus on the workers. And again, I make it clear it’s not just white male boilermakers or firefighters. It’s people of color. It’s young people. It’s this broad, broad working class in this country of 70 or 80 percent of the workers.

I’m sure you caught President Obama’s remarks this week about Twitter outrage and wokeness and how, to him, that isn’t productive activism. And I was thinking about that in terms of some of the people you write about in the book, people who were ostensibly unforgivably bad actors but were important in advancing some modicum of the progressive cause. How do you reconcile their contributions to the progressive movement with their complicated, problematic past?

Some things you never forgive, like being a KKK member. But you also embrace change. When you ask people to change and they change, you accept that, and you don’t keep pointing backwards and you welcome them to the struggle and the fight. Everybody in this book—including the guy who wrote it—is flawed in our careers and in our lives. I tried not to judge—although I probably did some—but I also recognized the unevenness of their careers and their fights.

Some look better than others. Only one started as a KKK member, and he became one of the best justices—he was burned in effigy at the Alabama Law School, after he did the Brown v. Board of Education decision. I think—though I’m not sure on this—he was one who really helped them to get to unanimous on it. So, you welcome that, you don’t forget it, you don’t entirely forgive it. I’m a white guy talking about a guy that belonged in the Klan, I understand that. I know all these senators were uneven. I also know in this book that everybody who held my desk was a Democrat and everybody who held my desk was a male and everybody who held my desk was white. I would assume that, after I leave the Senate, that the next five holders of this desk—I assume we’ll see people of color and women, as we should.

I wanted to ask you about the last chapter in the book. There’s a progressive movement of young people closely aligned with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and her allies who emphasize the idea of turning out voters who have historically not voted and have been underserved by government. In the book, you note that theory of change but advance another: You say it’s not just about engaging folks who haven’t been engaged, but actually trying to court some of the voters who used to be Democrats and have now turned away. Who do you think is right?

Well, I think we’re both right. I rely on people like her and others—my daughter is a council member in Columbus and she’s on the ballot again this year for a second term. She engages with young people all the time, as I do. It means getting new people to the polls, to be sure.

But you know, millennial workers—people working in restaurants and people who go to Columbus State Community College to be physical therapists and have a decent living, but never get rich and are going to struggle sometimes—they’re all part of the dignity of work. And those are people we’re gonna win. But if you talk about work—I mean, that’s what almost all of us have in common. We’re all doing something productive for our country. It might be moving back home for six months with your dying parent and putting her in hospice. It might mean staying out of the workforce for a year and raising a child. It’s always about family leave and having sick days. And that appeals to all kinds of workers. That appeals to people in a very upscale Columbus—which is now Democratic off the charts, though it was Republican, when I started in politics—but also appeals in Steubenville, which was 65 percent Democratic when I started and now it’s 40 percent Democratic.

I just have never subscribed to this view. I was told when I thought about the presidential race was you either talk to our progressive base or you talk to workers. And the answer is no, that’s a false choice. You never compromise on choice and guns and marriage equality, but you talk about worker rights. If you turn up the volume on worker rights, you’re going to appeal to everybody who feels that they haven’t had the chance to get ahead. I’m actually less likely than some of the young members of Congress to compromise on marriage equality and choice and guns because I’ve been beaten up on those three issues for 20 years and I haven’t compromised. So you do that without compromise, but you turn the volume up on talking to workers about the dignity of work.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.