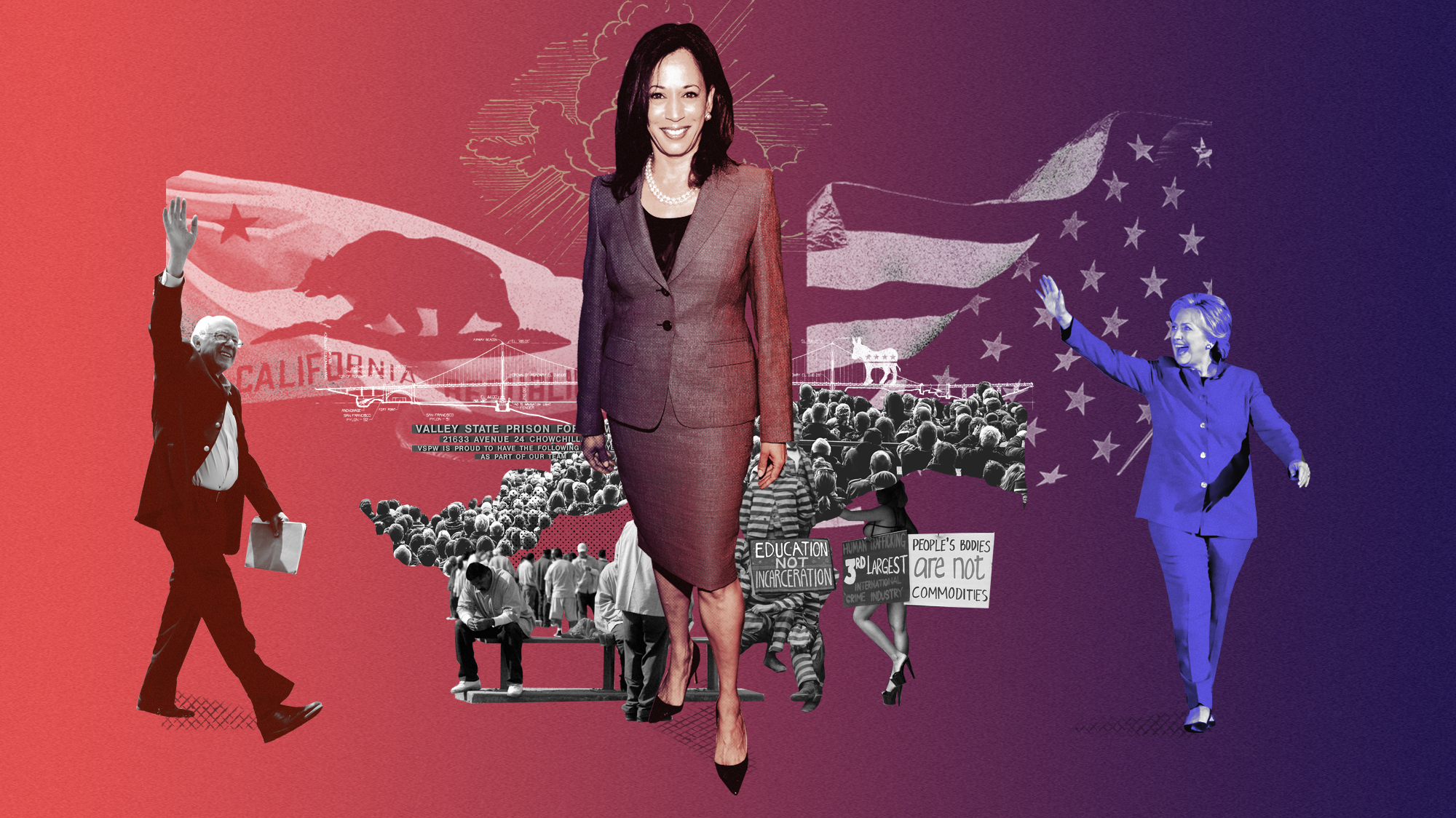

When I started reporting this story in the summer of 2017, Kamala Harris was a promising but still relatively new player to the national scene. She’d just been elected to the Senate, and having followed her career since her stint as district attorney of my hometown of San Francisco, I could tell that she had much wider ambitions. It wasn’t just her Senate win. Of course, the Obama comparisons didn’t hurt. But she was enough of an unknown at the time that she seemed capable of letting a broad range of people map their ambitions onto her.

In this story, I focused on criminal justice because, well, how could I not? Until she got to the Senate, Harris had spent the entirety of her professional career in law enforcement. The small but meaningful program she started as San Francisco’s district attorney, Back on Track, became the focus of my story. But in retrospect, I should’ve looked closer not necessarily at what she did, but at who she is. Harris represents a particular strain of Black American political thought: moderation. It’s the idea that change doesn’t come suddenly but slowly, piece by hard-fought piece, and is led by people who work to gain access to power. She was always going to be an uneasy fit in this political moment.

More than that, Harris is a Black woman who proudly served in law enforcement for more than two decades. It’s something she never got comfortable talking about on the campaign trail. I’d have been surprised if Kamala Harris hadn’t run for president this year—she’s just that ambitious. I’ll be surprised if she doesn’t try to run again. But the next time around, I hope she’s got more substance under her belt from her time in the Senate. —Jamilah King

Editor’s note: We’re looking back at some of our work from the past decade. The piece below was originally published in January/February 2018. Click the highlighted text for updates, elaborations, and the story behind the story.

Down road 22 in Chowchilla, behind a wall of trees, impossibly green despite the brutal summer heat of California’s Central Valley, is the country’s largest prison for women, home to about 3,000 inmates. For at least a decade, no member of Congress had visited the facility—until this sweltering Wednesday afternoon in July.

Dressed in a cream-colored blazer and black pants, a double string of pearls circling her neck, her softly highlighted, dark hair coiffed just so, Kamala Harris is on a fact-finding mission. “This is about my training as a prosecutor,” California’s junior senator tells me later. “I like to go to the scene, and I do that with almost [any] project. I need to see it and I need to hear it—I need to feel it, almost, so that I can have some intuitive sense, as well as some theoretical or intellectual or academic sense, of what’s going on.”

Harris and a small group of aides walk through hallways lined with inmate artwork, mostly watercolors, into a small classroom where four women, chosen by the warden to describe the facility’s mental health services, are ushered in. We sit in a semicircle as Harris introduces herself, leaning forward with her hands clasped: What’s your name? What’s your offense? Your sentence? Which county were you sentenced in? How often do your groups meet? How many people attend? Are those meetings happening weekly? Monthly? What are your plans for when you’re released? The questions come near rapid-fire; the atmosphere is intensely focused.

This is the Kamala Harris that millions of Americans saw during this past summer’s Senate Intelligence Committee hearings, when her persistent questioning—despite interruptions by male colleagues—made Attorney General Jeff Sessions admittedly “nervous.”

The trip to Chowchilla was designed to bolster Harris’ bona fides as a criminal justice crusader willing to stand up to the Trump administration’s tough-on-crime agenda. But as much as the trip was about Harris’ future, it was also about her past. As she likes to constantly remind people, she began her career as a prosecutor and has a near-obsessive, decadeslong interest in reforming incarceration, one that has followed her from the district attorney’s office into the state attorney general’s, and now into the US Senate.

And that is where things, at least politically, start to get complicated.

Harris has long tried to bridge the tricky divide between social progressivism and the work required as a prosecutor—sometimes more successfully than others. As San Francisco’s district attorney, for instance, she steadfastly refused to seek the death penalty against a man accused of killing a police officer, but later, as California’s attorney general, she defended the state’s right to use capital punishment. In 2012, she helped win a massive, $25 billion settlement with Wells Fargo and other financial institutions for foreclosure abuses, but a year later she declined to prosecute Steven Mnuchin’s OneWest Bank for foreclosure violations. In 2014, she co-sponsored a bill to outlaw the so-called gay-panic defense in California, a legal strategy that often shielded perpetrators of violent crimes against LGBT people from serious punishment, but a year later she sought to block gender reassignment surgery for a transgender prison inmate.

As a woman of color, she embodies two key Democratic constituencies, and she is beloved by the wing of the party that broke for Hillary Clinton. But among those on the far left, including many die-hard Bernie Sanders supporters, she’s an object of disdain, a Hillary-bot with weak progressive credentials. While that segment of the left might oppose anyone who isn’t one particular septuagenarian, the Week summed up this critique when it slammed Harris for her “rather Hillary Clinton-esque tendency to say the right thing but not follow through.”

The contradiction boils down to this: Harris is not interested in crusading from the outside; her mission is to reform the system from within. And no chapter of her life better reveals this dynamic than her days as a newly elected district attorney in San Francisco, working to get one radical program off the ground.

Kamala (pronounced comma-la) Devi Harris’ very existence is arguably a testament to the unique possibilities of 1960s California. Her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, emigrated from Chennai, India, to come to the University of California-Berkeley to pursue a doctorate in nutrition and endocrinology. Born and raised in Jamaica, her father, Donald Harris, was at the university earning a Ph.D. in economics. Shyamala was supposed to return to India and an arranged marriage, but she fell in love with Donald and political activism. Kamala was born in 1964, and she frequently talks of going with them to civil rights marches as a kid. She also tells a story that once, when she was fussing as a child, her mom asked what she wanted and she yelled back, “fweedom!”

Her family’s political legacy, though, stretches further back, to India, where her grandfather was active in the fight to gain independence from British colonial rule and her grandmother walked the streets with a bullhorn, telling poor women how to access birth control. “Both of my grandparents impressed upon me their conviction that we each have the capacity and the responsibility to work for a better and more just society,” Harris writes in her 2009 book, Smart on Crime.

Harris attended Howard University, where she majored in political science and economics and was inspired by a strong legacy of black achievement. In 2003, while campaigning for district attorney in San Francisco’s historically black Western Addition neighborhood, she told an audience of young people, “Close your eyes and imagine: Every Friday night, 10,000 students get dressed up and go out in the yard of Howard University. There is a yard filled with thousands of young people who look like you—and they are all college students!”

By the early 2000s, Harris was an up-and-coming lawyer in the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office working on child abuse and domestic violence crimes. Lateefah Simon was the executive director of the Center for Young Women’s Development, where the onetime single teen mom, then in her 20s, spent her days organizing young sex workers. The two formed an unlikely alliance. Simon was in the trenches confronting pimps; Harris was building cases against pimps and others involved in sex trafficking. Simon began accompanying Harris to “know your rights” sessions for women across the city, toting flip charts and an easel in the back of what Simon describes as Harris’ “beat-up BMW.”During her second year at the University of California Hastings College of the Law, her mom and some other family members asked what she would do “for the fight for justice” upon graduation. When Harris excitedly told them that she would become a prosecutor—she’d spent a summer interning at the Alameda County DA’s office in Oakland—she wound up having to defend the decision “like one would a thesis,” she recalled to Katie Couric. At that point, only 5 percent of the state’s district attorneys were nonwhite. But as she once told former Obama chief strategist David Axelrod, “When you want to improve a system, certainly there is a role to be played about marching and about banging down the door and sometimes on a bended knee. There is also a role, which is to be at the table where the decisions are made and influence the system from that perch, and that’s what I decided to do.”

Harris, right, receives the oath of office from California Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald M. George, left, during inauguration ceremonies, Jan. 8, 2004. Harris’ mother, Dr. Shyamala Gopalan, holds a copy of “The Bill of Rights.”

George Nikitin/AP

In 2004, after Harris defeated two-term incumbent Terence Hallinan to become San Francisco’s district attorney—the first woman and the first person of color to hold the position—she approached Simon about joining that office.

“I never wanted to work for The Man,” Simon says. “And she was like, ‘You’d be working for this black woman.'” When Simon demurred, Harris made her case more plainly: “You can bring your advocacy into the office, but do you forever want to be on the stairs yelling and begging for people to support you, your cause? Why can’t you fix it from the inside?”

It was as much a plea as a rallying cry. By then Harris was already formulating her specific brand of fix-it-from-the-inside activism, and one program she created as district attorney would come to embody it: Back on Track.

At the time, California led the nation in tough-on-crime legislation like three-strikes laws. As a prosecutor in communities like Oakland and Richmond in the early ’90s, Harris had had a front-row seat to the carnage the crack cocaine epidemic wrought on African American communities. “She [was] very clear that the war on drugs [was] an abject failure,” says Tim Silard, an advocate for civil rights and income equality whom Harris tapped to help run Back on Track. As Harris would later write of her time in the DA’s office, some 60 percent of the new felony cases annually were nonviolent drug crimes. “Many of the perpetrators are repeat offenders who commit a crime days after being released from jail or prison for the previous crime,” she explains in Smart on Crime.

Harris saw this as both a vicious cycle and a drain on resources. “Each one involves an arrest, a booking, a prosecutor’s time, a judge’s time, often a public defender’s time, a stay in jail of short or long duration, and a probation officer’s time, for which taxpayers foot the bill,” she writes in her book. “These crimes carry all sorts of collateral and psychic costs as well—the social damage of a neighborhood from drug dealing or the cost of putting an offender’s children in foster care.”

So she set out to build a program for people who, if reached in time, were less likely to reoffend: first-time nonviolent drug offenders, specifically those aged 18 to 30. If these offenders pleaded guilty, they could join a 12- to 18-month program of individualized support, which included job training, more than 200 hours of community service, and a requirement to find steady employment or enroll in school. It leaned heavily on public-private partnerships to create job and support services. The DA’s office reserved the right to jail participants if they broke any of the rules—even missing appointments—or were charged with another crime. At the end, there was a graduation at which a judge, who typically volunteered his or her time, would expunge the felony charge from the participant’s record.

Back then, this approach was revolutionary. “I remember looking for analogues,” Michael Troncoso, who served as assistant district attorney and assistant chief attorney for policy under Harris in the DA’s office, says about Back on Track. “It was a lonely space to be in at the time.”

Simon remembers brainstorming sessions in which the small team brought their legal pads and best ideas for what could make the program succeed. Harris insisted that some meetings with participants be held at the University of California’s law school instead of at the Hall of Justice—a hulking gray building attached to the county jail. “You don’t do programs to increase people’s options and life outcomes,” Simon says, by having them “come to the probation department to talk about what their dreams are.”

Harris opened up her Rolodex to find opportunities for participants. Simon remembers her reaching out to the Department of Public Works to ask it to hire people from the program. She talked 24 Hour Fitness into offering free yearlong memberships and even convinced the Art Institute of California-San Francisco to create scholarships for qualified participants. She persuaded public servants to volunteer overseeing hearings for those in the program. Harris, Silard says, “proselytized the hell out of [Back on Track].”

And it worked. While San Francisco’s longtime Public Defender Jeff Adachi says the program’s results are somewhat skewed because it targeted a small number of people—less than two dozen in most graduating classes—who “were seen as those most likely to succeed,” the statistics are hard to argue with. Back on Track had a reoffense rate of 10 percent, compared with rates of more than 50 percent among similar populations elsewhere in California.

For Harris, the program wasn’t just aimed at getting participants on their feet: It was also about building a team of activists within the criminal justice system, and persuading people who had spent time agitating from the outside to buy into making change from the inside. More often than not, that meant recruiting strong-willed women of color.

Joanna Hernandez, then a young Latina organizer, had spent her career doing on-the-ground mediation with at-risk and gang-involved youths. When Simon tried to hire her as a reentry manager for Back on Track, Hernandez saw the district attorney’s office as an enemy, not an ally. Hernandez remembers saying, “What do I look like working with the DA’s office?” She had her own ideas of how the system operated: “Prosecution, wrongful prosecutions,” she says. But like her boss, Simon was persistent, and Hernandez eventually joined up.

Hernandez considers her time with Back on Track as the key to finding effective ways to help some of the city’s most vulnerable. “A lot of young people don’t get those second chances anymore, and to be part of a historic program that offers that was empowering for me,” she says. “Especially seeing young people who grew up in the same neighborhood that I came from.”

Harris was an exacting boss. Staffers were expected to keep their offices clean, return calls promptly, and respond to emails immediately. Harris required Simon, who did not have a college degree when she started working for the DA’s office, to get one. Simon enrolled at nearby Mills College and Harris demanded to inspect her report cards.

Early on, when Simon showed up to a training in the city’s then predominantly black Bayview neighborhood wearing jeans and a hoodie, Harris took her aside. “Why would you ever disrespect your people? You work for this office. You work for the state, so you represent. Would you go to Pacific Heights”—one of the city’s whitest and wealthiest neighborhoods—”wearing that?” Simon recalls Harris saying. Later, Harris gave Simon a crash course on how to show up in a room, or what she called “executive presence.” When she was finished, she handed Simon a bag. In it was a brand new suit. It was Simon’s first, and it still hangs in her closet.

Today, Simon, who won a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2003 for her work organizing formerly incarcerated young women of color, is president of the Akonadi Foundation, a racial justice organization, and serves on the board of directors of the Bay Area Rapid Transit system. She ran for that office in the name of Oscar Grant, the young black man who was killed by a BART officer on New Year’s Day in 2009. She credits her current position to her work with Harris: “She saw me before I saw myself, in a lot of ways.”

Back on Track was an important win for Harris, who by 2009 was already eyeing statewide office. California was struggling with prison overcrowding, so Harris worked with the state Legislature and the Republican governor to get Back on Track signed into law as the model reentry program for the state. That positioned her for the attorney general’s office in 2011—and for the period when the conflicts baked into her fix-it-from-the-inside approach would erupt into full public view.

As district attorney, Harris had passionately argued that a man convicted of killing a cop shouldn’t face the death penalty because of its well-documented racial disparities. The move won some of her earliest national press coverage. But police unions denounced her, and during her first run for attorney general she appeared to align herself more closely with them by remaining conspicuously silent on hotly contested criminal justice issues, like Gov. Jerry Brown’s “realignment” that sent low-level offenders to county jails instead of state prisons. And then, as the state’s top law enforcement officer, after a federal court ruled that California’s enforcement of the death penalty was unconstitutional, Harris appealed, arguing that the ruling “undermines important protections that our courts provide to defendants.”

Left to right: Stockton Police Chief Eric Jones, California Attorney. Gen. Kamala Harris, Los Angeles County Sheriff, Jim McDonnell, and Los Angeles Police Department Chief Charlie Beck.

Damian Dovarganes/AP

Harris’ time as attorney general also coincided with what, on its face, would seem like a positive development for her political career: Criminal justice reform had become a widely accepted, bipartisan issue. The public awakening also made room for heightened scrutiny of police killings of black men and women in politically vulnerable communities. Scores of black activists called for accountability, but Harris mostly remained silent. While the Los Angeles Times endorsed Harris in her campaign for senator, it also wrote, “Harris has said California needs bold leadership, but a bold leader can’t sit out on significant decisions.”

Whether Harris is politically deft enough to navigate the defining tensions of her party remains to be seen. But I observed one way she might do so, in an overflow room of the Hart Senate Office Building in September. I was there with Bernie Sanders supporters watching on a small television as the Vermont senator introduced his “Medicare for All” bill. One middle-aged white man wearing tan cargo shorts and carrying a Bernie 2016 sign lingered close to the TV. Harris was one of 17 Democratic senators who had signed on to the bill—including nearly all the buzzed-about 2020 hopefuls, from Elizabeth Warren to Cory Booker. When it was her turn to take the podium, Harris opened with platitudes—health care shouldn’t be partisan, people should receive it regardless of where they live or what they earn—that coming from a more firebrand politician might have earned applause. The Bernie supporters seemed unimpressed.

But then Harris’ face lit up, her eyes grew wide, and her hands became animated as the economics major in her took over; you could almost see the flip charts turning in her head. The private sector, she said, often gauges what’s working and what’s not by looking at the return on investment. “The taxpayers of the United States deserve a better return on their investment,” she exclaimed to the crowd, which had finally started to cheer. She was hitting her stride, and at least that afternoon next to Sanders, she had started to bridge the divide she has so long tried to straddle. Even the man in the overflow room with the Bernie sign was nodding his head yes, seemingly buying into her argument—and into her.