Barcroft Media/Getty

A major bank that Elizabeth Warren once sharply criticized has some stark warnings for Wall Street investors about her potential presidency. Warren’s corporate tax plan, according to one memo the bank circulated, would “directly impact corporate earnings.” Her nine-point eligibility test for international trading partners—which requires a commitment to protect religious freedom and labor rights—“would disrupt global supply chains.” And her proposed 2 percent tax on personal wealth greater than $50 million “would likely crimp investment in the economy.”

Those are some of the conclusions reached by the research arm of Barclays, a powerful London-based bank and financial services firm. The series of five reports, titled “#DemNomination2020,” is intended to provide insights on “market-moving policies from this nomination cycle,” according to one of the documents. The reports systematically dissect Warren’s plans—at the time of publication, the researchers counted nearly 50—through the lens of the US credit, municipal, and equity markets, and they include a close evaluation of how much Warren could achieve without Congress’ help. Barclays prepared the reports in October and November for its paying clients—institutional investors such as commercial banks, hedge funds, and insurance companies.

“Given Senator Elizabeth Warren’s (D-MA) policies that she asserts are ‘big structural’ change and ‘economic patriotism,’ her quantifiably more liberal voting record, and her steady rise in the polls and betting markets,” the first report explains, “investors and corporates across asset classes and geographies have taken note and posed questions.” The reports coincided with Warren’s surge in national polls during the fall. Support for Warren has declined since then, but Barclays has not distributed similar analyses of her Democratic opponents’ proposals, according to a source familiar with the bank’s offerings. Barclays states in one of the documents that Bernie Sanders’ liberal record had also “elicit[ed] questions from investors and corporates” but that “Warren is certainly the focus.”

Mother Jones and other outlets have reported on pieces of the Barclays research, but a more comprehensive description of the memos has not previously been published. The bank did not respond to a request for comment.

Barclays’ overriding conclusion—that a Warren presidency would be bad news for financial titans and many large corporations—echoes the Massachusetts senator’s own message. On the campaign trail, she has rolled out a slew of proposals aimed at reining in big business and “holding Wall Street accountable.” The strategy set off alarm bells on Wall Street and drew ire from members of the billionaire class, including former Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein, hedge fund manager Leon Cooperman, and money manager Ron Baron. Warren, for her part, has reveled in the criticism.

I'm Elizabeth Warren and I approve this message. https://t.co/2Ewkbm0ZwA

— Elizabeth Warren (@ewarren) September 10, 2019

As the first caucuses and primaries draw closer, Warren has noticeably curtailed some of her most strident rhetoric on this front and has focused instead on arguing that she’s the candidate best positioned to unify and excite the party. Still, her promise to sidestep Congress and enact key pieces of her agenda through executive authority has played a key role in her closing argument. On Tuesday, Warren offered the latest example of this when she announced she would use an executive order to cancel student loan debt for 95 percent of borrowers.

In their October report on Warren’s impact on the credit industry, the Barclays researchers had warned of exactly this. Wiping out student debt, they wrote, would create a “material business risk” to companies for which the “net interest margin earned from student loan assets” made up “a substantial portion of earnings.” That’s not something Warren is likely to lose sleep over: Last year, she referred to Navient—a student loan servicer that Barclays deems among the most at risk under her plan—as “scammers.”

The Barclays reports spell out a number of similar doomsday scenarios for other sectors loathed by liberal activists. Closing tax loopholes, as Warren proposes, would “likely limit the size” of the private equity industry—an industry that Warren has described as “legalized looting” because of the way it buys and restructures companies. Banning fracking would be “broadly negative” for energy companies. The households subject to Warren’s wealth tax “would likely need to fund it by reducing their assets.” Warren’s plans to break up Big Tech—companies like Amazon, Facebook, and Google—would be “detrimental to the performance of these companies” and “erode the value of the companies that own them.” And, as Mother Jones reported last year, Barclays predicts that Swiss banks—which often serve as off-shore havens for the ultra-wealthy—would suffer, due in large part to the fact that their clientele are “the segment right in the middle of Senator Warren’s crosshairs.”

Barclays researchers also caution that Warren, who has often called for stiffer penalties for corporate lawbreaking, might choose regulators who “increase the monetary downside for companies accused of criminal and civil lapses.” Barclays found itself on the receiving end of that desire in 2012, when Warren wrote a Washington Post op-ed slamming the bank for “pad[ding] its bottom line by taking money from everyone else” during the Libor scandal, an international price-fixing scheme in which banks manipulated their interest rates in order to increase their profits and perceptions of creditworthiness. “Real accountability would mean prosecuting the traders and bank officials who violated federal laws and prosecuting the executives who knew what they were up to,” Warren argued at the time. “It would mean forcing executives to pay back any inflated compensation that was based on padded profits.”

But the real obsession of the Barclays research revolves around how much Warren could do without the help of Congress. As one of the memos notes, “Senator Warren could advance her agenda by empowering or constraining the actions of regulatory agencies and departments” or could use executive orders to enact pieces of it. In addition to her promise to cancel student debt with the stroke of a pen, Barclays emphasizes her ability to unilaterally end oil and gas leases on federal lands and dictate the terms of international trade. “As illustrated by the current US administration’s trade war with China, the US president has wide-ranging authority to conduct trade policy,” one memo notes. “[W]hile the proposals are likely to be challenged by Congress, Senator Warren will presumably be able to implement a significant portion of her Trade agenda.”

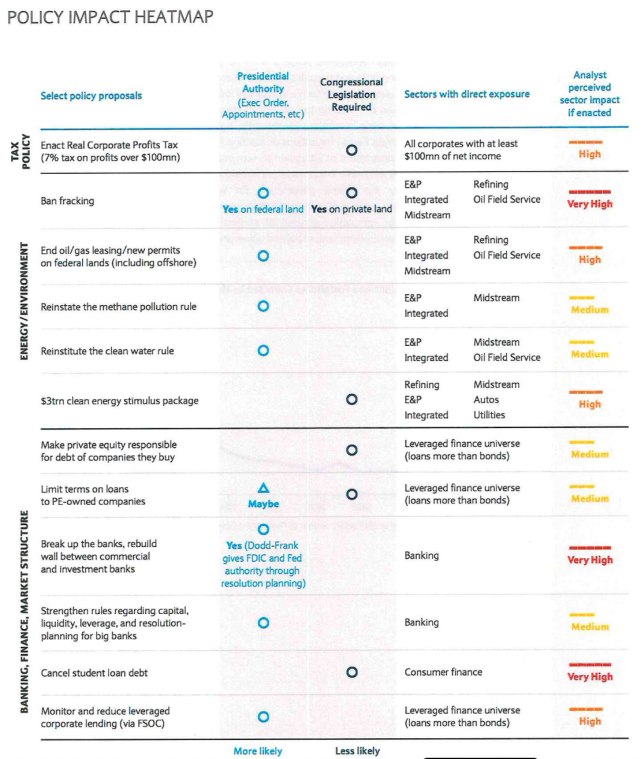

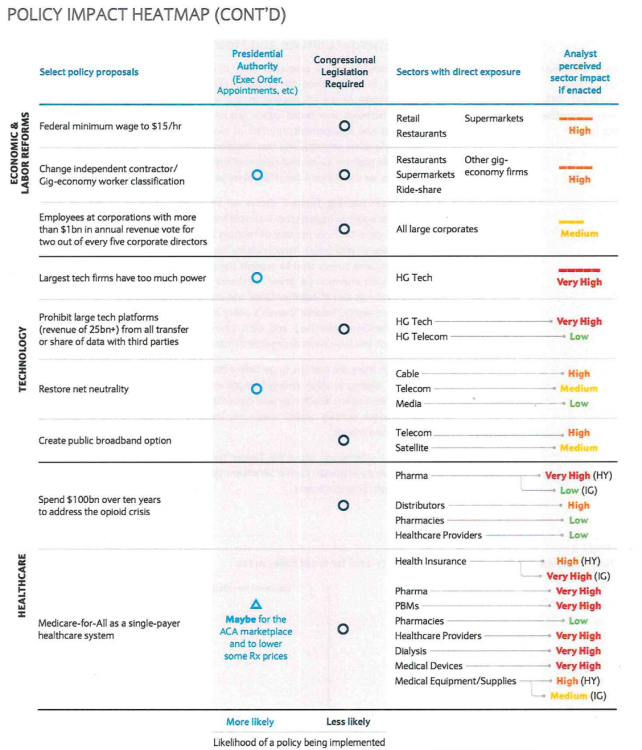

These charts, from Barclays’ report on how a Warren presidency would affect the US credit markets, indicate which of her proposals could be enacted by executive action and which sectors and companies would be affected as a result.

But for all the hand-wringing over what Warren would mean for big business, the Barclays researchers take care to note that Warren’s plans also present real opportunities for certain sectors and consumers. “The market appears to be defaulting to a view that Senator Warren’s political ideology would be a uniform negative for US business,” one report reads. “In our opinion, this is too simplistic.” If Warren could successfully break up big banks, for example, it would benefit smaller regional banks that have suffered under increased industry consolidation. Companies that produce electric vehicles, like Tesla, would benefit under her push for zero emissions for passenger vehicles by 2030, even as companies that make traditional internal combustion engines would suffer. And her proposed increase in the minimum wage would raise spending among working-class Americans—or, as the reports describe them, “lower income groups who have a much great[er] propensity to consume their disposable income”—which could be a boon for retailers and auto dealers.

But that, of course, is Warren’s point. “Government could help grow the economy, could create opportunities, could support small businesses and entrepreneurship,” she said in an economic policy speech at New Hampshire’s St. Anselm College last month. “But instead, we have a government that works only for those at the top.”