Mother Jones Illustration

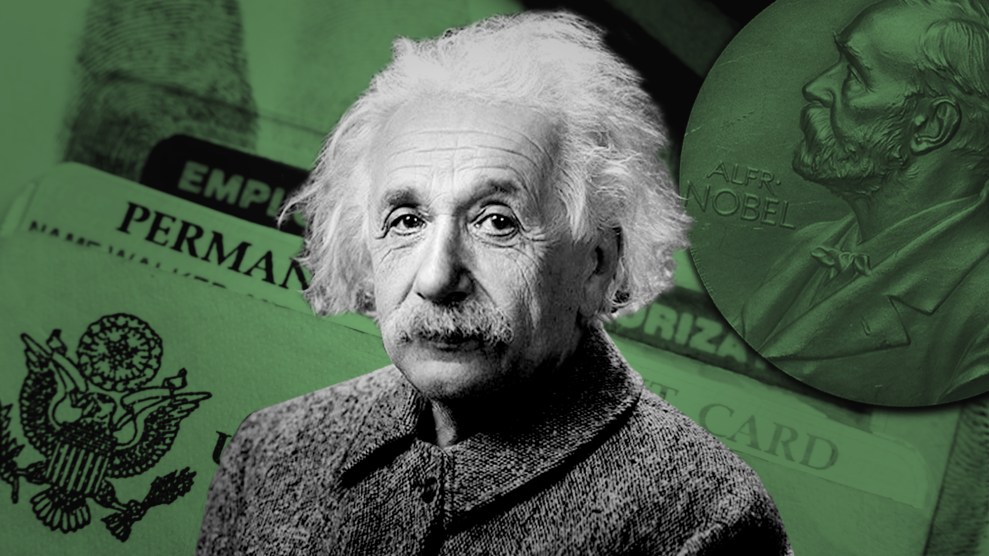

In early 2017, Robert Michael, a lawyer in New York City, was contacted by a client who wanted to apply to become a permanent resident of the United States. Specifically, the client, who lived in a largely Muslim country, hoped to get an exceptional ability green card, which are issued to non-citizens with “a degree of expertise significantly above that ordinarily encountered in the sciences, arts, or business.” Michael is a bankruptcy and commercial lawyer as well as an expert on Islamic law, and usually does not handle immigration cases. Yet he had little doubt that his client would meet the stringent criteria for what’s known as the genius green card or Einstein visa: After all, they had won a Nobel Prize.

Yet in April 2017, the government rejected the Nobel laureate’s application on the grounds that they had failed to present adequate “evidence of a one-time achievement—a major internationally recognized award.” In other words, they had not provided enough proof that they had in fact received a Nobel.

“For them to say that that we had not established that this person had won the Nobel Prize because of a missing bunch of meaningless formalistic words is nonsense,” says Michael, who asked not to reveal details about his client’s identity, including their gender, nationality, or what they won the Nobel for, because they felt that speaking out might affect their work. (Mother Jones has confirmed the identity of his client, who said they did not want to speak on the record.)

The Nobelist’s green card application was rejected a month after President Donald Trump had blocked travelers from five Muslim-majority countries (as well as North Korea and Venezuela) from entering the United States. Michael suspects that this and other anti-immigrant policies had something to do with his client’s denial, even though the official reason centered on technical details such as the application’s failure to detail the qualifications of the interpreter who had translated the Nobel Prize citation from Swedish into English. “What drove me nuts is people in the administration should have been on their hands and knees begging [the client] to come and celebrating the fact that [they] wanted to, given the politics of the time,” Michael says. “Instead they were putting up ridiculous roadblock after ridiculous roadblock.”

Michael beefed up his client’s application and resubmitted it to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the agency that issues green cards and visas. “We now knew that we had to, to use an inappropriate phrase, be ‘holier than Jesus,’” he says. “We had to get every I dotted, every T crossed.” In early 2019, USCIS approved the Nobel laureate’s genius green card. “We’re better as a country for someone like that wanting to come to live in the United States,” Michael says.

The EB-1 green card is meant to be a fast track to residency status for “aliens of extraordinary ability” who are on the top of their fields. It has been issued to Nobel Prize winners and nuclear scientists as well as athletes and actors. It’s one of the few visas that does not require the applicant to have an American employer or sponsor. Recipients include Yugoslav tennis champion Monica Seles, British singers Sarah Brightman and Craig David, and the late Dutch actor Rutger Hauer. John Lennon and Yoko Ono received a form of this visa in 1972. In 2001, future First Lady Melania Trump received an exceptional ability green card for her work as a fashion model, one of five granted to Slovenians that year.

This path to permanent residency has never been easy, but it has become much more difficult since Trump took office. According to USCIS data, approval rates for EB-1 extraordinary ability green cards have dropped from 82 percent in the 2016 fiscal year to 56 percent in 2019. Immigration attorneys say the Trump administration is interpreting the rules for genius green cards more narrowly than previous administrations, rejecting highly qualified applicants including researchers, athletes, and journalists.

These decisions appear to fly in the face of President Donald Trump’s own statements about his immigration priorities. At a White House Rose Garden ceremony where he unveiled his “merit-based” immigration plan last May, Trump said he wanted to prioritize admitting doctors, researchers, and other professionals with stellar academic records. “Under the senseless rules of the current system…we’re not able to make those incredible breakthroughs,” he said. “We want these exceptional students and workers to stay, and flourish, and thrive in America.” During his most recent State of the Union address, he said his administration is “working on legislation to replace our outdated and randomized immigration system with one based on merit.”

Despite Trump’s claims that wants to make it easier for high-skilled immigrants, his administration has already enacted new restrictions on those who seek to stay in the country. It has been rejecting H-1B visa applications at an unprecedented rate, denying these coveted temporary work visas to well educated professionals including pathologists, architects, and computer programmers, according to an analysis by Mother Jones and Reveal. A similar trend appears to be playing out with EB-1 green cards for highly accomplished people.

Dobrina Ustun, an immigration attorney in Dallas who specializes in extraordinary ability visas and green cards, describes the cases of two European journalists whom she recently represented. The two had almost identical professional profiles: Each was the editor-in-chief of an international magazine in their respective countries and had won multiple awards for their work. Both had been written up in publications such as Time and the New York Times and both had been fellows at a highly competitive program at Stanford University for experienced journalists from across the globe. The one who applied for an extraordinary ability green card during the Obama administration was approved. The one who applied under the Trump administration was rejected.

Ustun shared some of the “gems,” as she puts it, from the correspondence she received from USCIS asking for additional information before it denied that journalist’s application. The agency said that the Stanford fellowship didn’t count as an award and said that the application didn’t provide enough evidence to show that the New York Times is a major publication. Most remarkably, it said the applicant’s work experience as an editor was irrelevant. “Since you are petitioning as a journalist, your work as an editor does not count,” USCIS wrote. “It’s like they’ve already made up their minds when they send requests for additional documentation,” said Ustun. “It’s a disturbing trend.” (The journalist has filed a lawsuit against USCIS.)

According to USCIS data, applicants for extraordinary ability visas who receive requests for additional documentation are more likely to be denied than those who don’t. For applications who received requests for additional documentation, the approval rate fell from 48 percent in fiscal 2016 to 34 percent for fiscal 2019.

In an email, USCIS spokesman Matthew Bourkes said the agency won’t comment on individual cases. But he stated that the Trump administration has no “scheme” to limit high-skilled, employment-based immigration. He said that the variation in approval rates is a function of many factors including the number of petitions received. He also said that the extraordinary ability visa has historically had a 55 percent approval rate, on average. However, this figure is based on data from 2005 to 2010.

In 2010, Andrey Chursov immigrated from Russia to Germany to get a Ph.D. in bioinformatics and computational biology. He graduated with distinction from one of Europe’s top universities in three years. When I met him at a library close to his office in Redwood City, California, he blushed when I asked him if it was unusual to get a doctorate so quickly. “I just worked a lot,” he said.

The 33-year-old is now a senior scientist in the R&D unit of the biotechnology company Guardant Health, where he analyzes massive amounts of data using artificial intelligence algorithms to make predictions about the early detection of cancer. His path from Magnitogorsk, an industrial city near the Ural mountains, to Silicon Valley is impressive. After working in Germany, he cofounded a company in Boston that conducted successful clinical trials of anti-cancer vaccines on animals. When its funding ran out, Chursov joined the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, working on an H-1B temporary visa. Chursov has two pending patents and has co-authored eight articles in major journals. Distinguished professors and top researchers from Harvard, Yale, and the Mount Sinai School of Medicine have praised his contributions to genetics and biotechnology as “original” and “innovative.” Sherman Weissman, a professor of genetics at Yale School of Medicine, describes Chursov’s work as “entirely new” and “novel.”

Chursov and his immigration lawyers thought he had an excellent chance of getting an extraordinary ability green card. He applied for one in July 2017; USCIS rejected his application three months later. In April 2018, he sued USCIS to dispute its decision. Federal Judge Kevin Castel of the Southern District of New York ruled in his favor, finding that the agency’s “failure to adequately consider the totality of the submission was arbitrary and capricious.” Castel wrote that USCIS had disregarded Chursov’s reference letters from Ivy League deans while it “excessively focused” on things like how many citations he had on Google Scholar. Castel ordered USCIS to reevaluate the application and awarded Chrusov nearly $25,000 in attorney’s fees.

“The way that USCIS handled this case goes to show you the kind of impact these restrictive EB-1 adjudication policies can potentially have with regard to science in the United States,” says Sarah Edgecomb, an immigration attorney in Boston whose firm focuses on genius visas.

Edgecomb said she was surprised Chursov’s green card application was denied. “While he may not be one of America’s top 2 or 3 cancer researchers, obviously the guy is VERY good, and he ought to be the kind of person that we should be encouraging to come here and stay here,” she writes in an email.

Stephen Yale-Loehr, an immigration law professor at Cornell University, also reviewed materials from Chursov’s application. “This was a strong case,” he writes in an email. “It is too bad that Mr. Chursov had to go to federal court to win. In prior administrations, this case would have been a slam-dunk approval.”

USCIS has reopened Chursov’s application and has asked for more evidence of his professional qualifications. “I feel really devastated and distraught,” he says of the two-and-a-half-year process. While Chursov waits for a new decision, he is working on a temporary work permit. He hasn’t visited Russia because he worries about difficulties getting a new visa to return to the United States. He hasn’t seen his family in three years. He choked up when he talked about missing his grandmother’s funeral.

Being in limbo has also affected his efforts to make kinds of “incredible breakthroughs” Trump has said he wants to encourage with his immigration policies. To avoid any hassles, Chursov doesn’t travel to international conferences to present his work. “It looks a bit strange to me because in my opinion cancer research shouldn’t be limited by borders because people can have that disease in any country in the world,” he says. “When you get limited with such bureaucracy, it makes everything more complicated.”