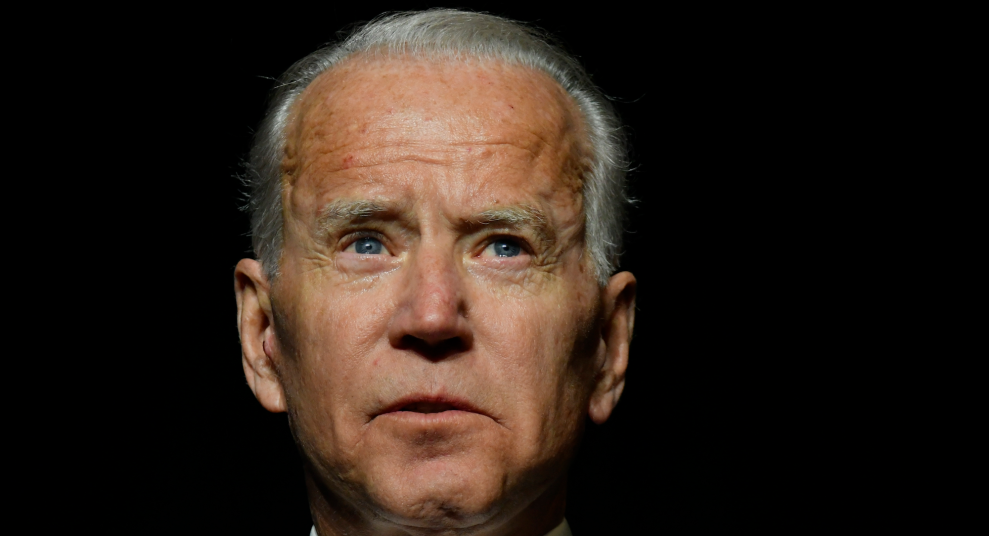

Vice President Joe Biden at a 2015 event where he spoke about preventing sexual assault on college campuses.

Paul Vernon/AP

Earlier this week, the New York Times, Washington Post, Associated Press, and NBC News published investigations into claims by Tara Reade that former Vice President Joe Biden sexually assaulted her when she was a staff assistant to the then-senator more than 25 years ago. The reports did not determine whether Reade’s allegations were true. Journalists interviewed one unnamed friend who said Reade told them in 1993 about the alleged assault, as well another friend and her brother, who said she told them “over the years about a traumatic sexual incident,” according to the New York Times. Other people Reade said she shared some details with, as well as her former supervisors and other Biden staffers, told reporters they had no memory of Reade’s complaints about him. Biden’s presidential campaign denied her accusation. “This absolutely did not happen,” deputy campaign manager Kate Bedingfield said.

So far, Reade’s story, which first came out as Biden was cementing his status as the Democratic presidential frontrunner, has not shaken up the race or substantially shifted public opinion about him. But the new allegations have been profoundly jarring for survivor activists, many of whom have long considered Biden a political ally on sexual violence policy and would like to see President Donald Trump defeated in November. In interviews, prominent advocates and organizers expressed frustration with how Reade’s claims have been handled by the media and politicians and detailed how they have been grappling with their own responses.

“For me, this is extremely painful,” said an advocate who had worked with Biden’s office on sexual violence issues during the Obama administration. She asked to remain anonymous because she worries that expressing support for further investigation into Reade’s claims could jeopardize her chance of working with the White House if Biden wins. “I really saw Biden as a champion for a really long time,” she said. “I’m experiencing cognitive dissonance right now. I haven’t had the ability or the time to process emotionally what it means for me to believe that he did this.”

“It’s just murky,” said Heather Marlowe, a survivor activist in California who works to improve police investigations of sexual violence. Because Reade’s allegations were not investigated at the time, she said, “It does become sort of a trial by media. It’s just egos and money, and Tara Reade just flounders.” (According to Reade, she reported sexual harassment, but not assault, by Biden to her supervisors and to the Senate in 1993. The four outlets that investigated Reade’s allegations could not find the complaint.)

Sage Carson, a survivor advocate, said she is personally angry about the way the allegations against Biden have been treated differently than those leveled against Justice Brett Kavanaugh when he was a Supreme Court nominee in 2018. “This is just further evidence that survivors will always be political pawns,” she said. “I’m extremely frustrated to see so many people who publicly came out and said that they supported survivors during Kavanaugh only then to do a 180 when it was someone within their own party.”

“We had these past two and a half years where folks have said, with the MeToo movement, ‘We’re going to start listening to survivors’ voices, we’re going to start taking allegations for what they are, treating them as if they’re credible and investigating rather than just brushing them off.’ Now we have two men running for president who have been accused of sexual assault,” said Alyssa Leader, a former victim advocate and rape crisis counselor who is now studying to become a lawyer for survivors. (At least 23 women have accused Trump of sexual assault, unwanted touching or kissing, or other inappropriate sexual behavior.) “That, for me, as a survivor, and as somebody who speaks publicly about these issues, is extremely frustrating,” Leader said.

Reade was one of eight women who last year publicly accused Biden of having kissed or touched them in ways that made them uncomfortable, telling a Nevada newspaper that he used to touch her shoulder and neck, and that she was asked to serve drinks at an event because Biden liked her legs. (Biden acknowledged that some of his “gestures of support” made people uncomfortable and promised to be “more mindful” of shifting norms about personal space.) Then, on March 25, Reade told podcast host Katie Halper that in addition to the alleged sexual harassment, in the spring of 1993, Biden pinned her against a wall and reached under her skirt and penetrated her with his fingers. She said she had not previously come forward because she was afraid.

Wagatwe Wanjuki, an anti-rape activist who worked with Biden’s staff to transform campus sexual assault policies during the Obama administration, said she couldn’t bring herself to listen to Reade’s podcast interview. “I just didn’t want to be triggered,” she said. She recalled meeting Biden at the 2016 Oscars after a Lady Gaga performance dedicated to survivors, where the then-vice president held onto her hand for longer than was comfortable, though she did not consider it sexual harassment. From reading the transcript of Reade’s account, she thinks it sounds “typical” of what she’s learned about sexual assault over more than a decade of advocacy. “It’s common for survivors to hide some details of their stories,” Wanjuki said. “Just to share a part that feels safer to disclose.”

Some of the activists I spoke with were pained by the reactions to Reade’s story, from the daily Fox News coverage to speculation that she may be lying due to her political preference for Sen. Bernie Sanders or her peculiar affinity for Russian President Vladimir Putin. “I had to get off Twitter yesterday,” the advocate who had worked with Biden’s office told me. “I started reading this coverage first thing in the morning, and my physical body and my trauma were having a response to it.”

Reade’s accusations have been met with skepticism from some prominent feminists. Earlier this month, actor Alyssa Milano—whose 2017 tweet asking survivors of assault and harassment to reply “me too” launched the #MeToo hashtag—told radio host Andy Cohen in that she still supported Biden. Women should be believed, Milano said, “but that does not mean at the expense of not giving men their due process and investigating situations. It’s got to be fair in both directions.” Journalist Joan Walsh shared a related reaction in the Nation: “It’s true, for a time, that one of the slogans that emerged from the nascent #MeToo movement was ‘Believe women.’ But it was never that simple; nobody ever said, or meant, ‘Believe every woman, no matter how incredible or undocumented her claim.'”

Even though they believed Reade’s story could be true, some survivor activists said that they still intend to vote for Biden. They cited several reasons, including the importance of federal judicial appointments; the experience of Biden’s staff on sexual violence policy; and their eagerness to replace Trump’s cabinet, including Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, whose overhaul of campus sexual-assault policy has prompted outcry from survivors. “I’ve always said I will never vote for somebody who has been accused of sexual harassment or sexual violence,” said Leader. But she still plans to cast a ballot against Trump. (In a post on Medium, Feministing cofounder Jessica Valenti expressed a similar sentiment: “I’ll do what’s right for the country and vote for him. But I’m still furious.”)

But others are considering not voting at all. “I haven’t completely written off participating in the election this fall, but the way we’re approaching it, I’m probably gonna wait until the last night and make my decision,” Wanjuki said. Marlowe, who was already critical of Biden’s record on criminal justice, said she will likely sit out the election.

Advocates also said they were disappointed about the response from lawmakers who have made fighting sexual violence and harassment part of their political brands. When WNYC radio host Brian Lehrer asked Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand on Tuesday if Reade should be believed, the New York Democrat stood by her support of Biden, whom she endorsed last month. Gillibrand said she believed the allegation against him was “different” than that against Kavanaugh. “Vice President Biden has a strong record for fighting for women in his life,” she said. “We are right now at the investigation stage of the allegation.”

When Mother Jones reporter Kara Voght asked Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) whether the allegation against Biden gave him pause, Khanna—who has sponsored bills to combat sexual harassment and supported the ouster of California’s Democratic Party chair due to allegations of sexual misconduct—said the vice president is “a decent, moral person.” Khanna added that he supports Biden as someone whom President Obama had “thoroughly vetted.”

“Some people are certainly responding the way that they are because of political calculus,” said Robyn Swirling, who runs Works In Progress, a nonprofit that helps progressive organizations and campaigns with their internal response to sexual harassment. “Right now, there’s a lot of ‘Blue no matter who.’ It’s been really disappointing to see voices who are otherwise very outspoken on these issues be silent or make excuses like, ‘Well he has a record of fighting for women on the policy level.'”

On Tuesday, Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) said at an online event that “it’s legitimate to talk about” Reade’s allegation. “If we again want to have integrity, you can’t say, you know—both believe women, support all of this, until it inconveniences you,” she said. Sanders, who endorsed Biden on Monday, followed Ocasio-Cortez’s lead two days later, saying it was “relevant” to talk about Reade’s allegations. “I think any woman who feels that she was assaulted has every right in the world to stand up and make her claims,” he told CBS This Morning. “I think that she has the right to make her claims and get a public hearing, and the public will make their own conclusions about it.”

The reluctance to speak publicly about Reade’s allegations extends beyond politicians. Eight national organizations that advocate for sexual violence survivors did not respond to a request for a comment or interview. In a statement, RAINN (the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) echoed the Biden campaign’s call for Reade’s claims to be thoroughly examined by journalists. “We appreciate that the media is investigating Tara Reade’s allegations and urge that they be scrutinized fairly and rigorously,” RAINN press secretary Erinn Robinson said. Terri Poore, policy director for the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence, declined to specifically address the allegations against Biden. But, speaking broadly, she said that her organization supports “all survivors” of sexual violence. “Where people have transgressed or caused harm, now or in the past, they must be held accountable,” Poore said. “We don’t believe anyone’s behavior is above scrutiny and discussion. No one gets a pass on this.”

The advocate who requested anonymity believes she’s not the only one feeling internal pressure to stay silent not just because it could hurt Biden’s electoral chances, but also because it could kneecap advocacy for survivors. If Biden wins, she said, she hopes to implement “a huge policy agenda” undoing Trump’s policies on sexual violence. “There’s a ton of people like me, who want to be changemakers on the inside and the outside, and don’t know what it will do to their ability to be a changemaker on the inside if we rightfully say at this moment, ‘There needs to be an investigation, and this is unacceptable.”

She would like Biden to pause his campaign until there is a formal investigation. Wanjuki said she’ll be paying close attention to how he responds to the allegations: “That’s how I can tell whether I will trust him or not.” Swirling would like Biden to take responsibility for more of his past behavior. “All of us are different people than we were in 1991 and 1993,” she said. “All of us have grown and changed in our understanding of appropriate conduct, how to respond compassionately to sexual assault allegations, our understanding of what comments are OK to make, or of consent. It would just be nice to see that acknowledged.”

Poore said it should be up to survivors to determine what accountability looks like. “In all cases,” she said, “we really need to look at what the survivor needs and wants and is asking for.”

So what does Reade want? In her podcast interview with Halper three weeks ago, she said that she just wanted people to hear her story. “I’m hoping by coming forward with this—and I know it’s hard to listen to, and it’s hard to live in it, right? But my justice now, the only justice I can have,” she said, “is to be moving freely in the world and to heal and not be silenced.”