“Life in these mountains ain’t always been easy, so people around here take a stand when they see something they don’t agree with—and I’m one of them,” says walrus-mustached Jammie Hale in his thick southwestern Virginia mountain accent. “People that grow up in places like this, seeing their environment destroyed, it stirs them, it causes people to want to get involved, and that’s why I’m here.”

In a documentary-style video produced by Unicorn Riot, a left-wing media collective, in 2018, Hale explains his decision to join a protest movement taking on the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP), a 303-mile long, nearly 42-inch-wide pipeline intended to move natural gas from the fracking fields of northern West Virginia to a terminal in southern Virginia that connects to markets and export terminals on the East Coast. Settled in among the hardwood trees on Peters Mountain, near where another (pseudonymous) activist known as Nutty has been occupying an aerial platform, he talks of his family’s 150-plus years in Giles County, Virginia, and how that history motivates him to do all he can to prevent the pipeline from crossing the Appalachian Trail.

Now in 2020, the Peters Mountain blockade no longer exists, and although many tree sits have fizzled out, a group of up to a dozen activists have been camped in a steep hollow along Yellow Finch Lane near Elliston, Virginia, for nearly a year and a half. (Hale lives nearby and visits the encampment several times each week.) It is at least partly to their credit that the Mountain Valley Pipeline remains unfinished. Its production cost has risen from a projected $3.5 billion to $5.5 billion, and the pipeline is two years behind its original timeline due to a series of regulations and litigation preventing it from crossing the Appalachian Trail and multiple rivers and waterways.

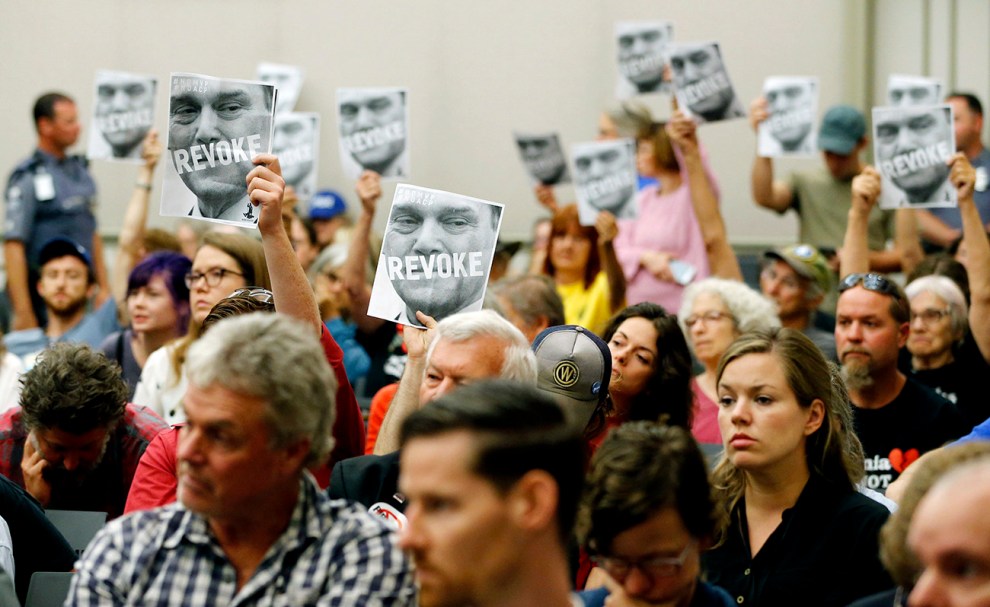

Heather Rousseau/The Roanoke Times/AP

Yellow Finch, as the encampment has come to be called, is giving its full-time activists, most of whom are in their 20s, an on-the-ground education in Appalachian direct action. They’re learning how to talk to media, to establish and maintain a defensible blockade in the forest, and to survive a winter in the mountains, all in a region written off by much of the US as “Trump country.” Less explored is the region’s significant history of activism that brought together outsiders and locals to resist corporate exploitation, from the labor organizing by Mary Harris “Mother” Jones on behalf of West Virginia miners in the 1910s and ’20s, to the Mountain Justice campaign against mountaintop removal coal mining a century later. Some veterans of the latter campaign are now working with the folks at Yellow Finch, applying lessons learned in the current fight against fossil fuels.

The camp lies at the base of the steep Blue Ridge Plateau; to reach it, you must drive carefully up a twisting mountain backroad and then back down a dirt road that follows a stream. Steep slopes rise up on either side, and the contrast between sides of the hollow stand as a testament to the activists’ success in delaying pipeline construction. On one side, the forest has been stripped bare, replanted with grass, and shored up with silt fences and green, mulch-stuffed fabric socks to prevent erosion. The other side of the hollow, home to the Yellow Finch encampment, remains wooded.

The camp is set about 50 yards up from the road, firmly planted into the hillside. A couple of hastily erected plywood buildings covered in handmade art and cardboard signs serve as a sleeping area and pantry. Tarps nailed to the side of the bunkhouse and nearby trees cover a makeshift kitchen, scattered with dishes, cooking gear, herbal tinctures, nutritional yeast, and other supplies.

The number of activists that call the camp home fluctuates with the weather and the need for additional people to sustain the camp. A 27-year-old activist called Gator fondly describes the camp’s occupants as “a bunch of badass queer anarchists that held it down for a long period of time.” They come from all over and vary in age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and family backgrounds, but they’re united in their desire to protect the mountains. They found the camp through a variety of paths; several cut their teeth in other movements, organizing against the mining of frac sand, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, mass incarceration, and police violence. They discovered Yellow Finch through word of mouth, on news sites popular with anarchists like It’s Going Down and Unicorn Riot, and Appalachians Against Pipelines, the campaign’s quasi-official Facebook page. Several came after seeing the video that featured Hale.

One of the camp mainstays is known as Dustie Pinesap. She grew up in the Midwest, then trained in tree-climbing and forest defense in 2017 and 2018 against Pennsylvania’s Mariner East pipeline system before coming to Yellow Finch. “You don’t need to be able to climb a tree,” Pinesap said. “You can cook food. You can bring supplies. You can build structures. You can chop wood. There’s a lot of things to do.”

Pinesap recalls how poorly prepared Yellow Finch was for its first winter, but how MVP’s rival camp was even worse. Pinesap remembers security guards clad in cotton uniforms, shivering and staring at their phones in a tent heated with propane—what she called a “carbon monoxide special.”

“They’re out of their element and they don’t really know what to do,” Pinesap says. “We’ve got a fire here, we can cook over a fire. We fill in the shack and warm up by the woodstove. We’re chopping wood, we’re doing things, we’re being active. They [pipeline security] are sitting around like you would at an office job.”

Joe Mahoney/Richmond Times-Dispatch/AP)

Part of the power in the activists’ mission comes from the community support they have managed to garner. Though Hale and another local supporter, Crystal Mello, don’t live in the protest camp, they offer up their homes for the Yellow Finch folks to take showers and do laundry; they haul socks, toilet paper, food, and other supplies up the mountain each week. The broader population in communities along MVP’s route tolerate Yellow Finch and the broader anti-pipeline campaign; many support their efforts outright. Handmade anti-pipeline signs appear along the roads near the pipeline, while visible pro-pipeline sentiment is non-existent. The biggest problem, Mello says, is a sense of fatalism that pervades the community: “Nobody likes this pipeline, but everybody says, ’It’s stupid, but what are you going to do, it’s coming anyway.’ It’s the saddest conversation.”

Mello, who became fast friends with Hale upon meeting him at the encampment, monitors law enforcement vehicles on the road to the camp with the help of a network of other locals. If any are spotted, she heads out to the Yellow Finch site to try and defuse the situation or, in case of arrest, provide jail and court support.

They make an odd pair. Mello, a 44-year-old single mother and grandmother, earns a living cleaning houses and emphasizes her local roots by wearing clothes bearing logos for the nearby high school and community events like the Eastmont Tomato Festival. At camp, she often takes the “gate” chore—a boring but essential job monitoring who approaches the camp—and she even spent a few days in one of the tree sits. Hale is one of the rare white cis men among a group comprised of mostly gender nonbinary activists. Both Hale and Mello feel fiercely protective of the younger camp activists; Mello compares them to her kids’ friends, while Hale has at different times jawed with pipeline security and scuffled with a state trooper for picking on the protesters, earning misdemeanor assault and disorderly conduct charges. He was found not guilty of the first, but convicted and sentenced to 30 days on the second. (He has appealed the ruling.)

Still, Hale says he’s learning a lot from the pipeline fighters about white supremacy and gender politics. He’s learned about violence against transgender individuals, women, and people of color. They’ve broadened his worldview. “I’ve always been kind of a hermit,” Hale said. “I took care of myself and my family and liked to be left alone. Through this journey, I’ve had to step out of so many boxes. I’ve had to step outside of my comfort zone, like with pronouns. I never thought it was that important, but to some folks, it is. I’ve become more sensitive to folks.” In return, he shares his homesteading skills.

“Me being a mountain person, I hoped I’ve shared how to stay warm, how to stay dry, how to prepare water,” Hale said. “I hope these folks have learned from me, but I’ve learned way more from them. Before I started this, it was all about me. It was all about my farm and my family, and not about anyone else. But after I met these young folks living in the woods and coming up with random acts of kindness, it’s really touched my heart and opened me up.”

Don Petersen/Roanoke Times/AP)

Before he got involved in the Peters Mountain blockades documented by Unicorn Riot, Hale worked as a janitor at a state university until he tore the muscles in his back and shoulders while on the job. Hale sued and won early retirement. Since then, he had focused on keeping up his farm, caring for cattle, goats, pigs, and chickens. Fishing and hunting were his main pastimes. “I never was political until I started this journey,” Hale said.

That journey began when he spotted a pipeline crew surveying land on his neighbor’s farm. Hale had been charged with watching the property while his neighbor was out of town; he reported the trespassers to the police. When a local deputy declined to arrest them, Hale was furious. He connected with other pipeline activists on Facebook and learned about the Peters Mountain tree sits on the news; in February, he received a text from another local about Nutty’s aerial pod. Hale spent 52 days at Nutty’s support camp before joining up with jail and court support for activists who are arrested, and he began visiting Yellow Finch a few times each week.

In the Unicorn Riot video, Hale talks about what he’s going to do next: “I’ve seen Mountain Valley pipeline stocks go down, and that’s where my target is. If I stand to lose what I’ve worked all my life for, and I can hinder their process, I figure that’s fair justice.”

In the two years since, Hale has indeed lost much of what he once worked for. He has sold off most of his livestock, in part to fund his work, but the pipeline construction has dried up their ponds anyhow. He once ran cattle, but now he is down to four goats and 10 pigs. He insists that he regrets nothing, despite being stuck at home, waiting to hear the outcome of his appeal.

“I’m working on trying to be disabled and still be useful in life,” Hale said. “Now, I’m disabled and trying to be disruptive.”