Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Jaylnn Schroeder, an Instagram influencer with 50,000 subscribers, seems like any one of the thousands of people who have grown an audience on the platform by presenting a curated glimpse of their life. With a bio of “Sharing my Passions + Purpose” that notes “I believe in love + light + 🍟,” she mostly posts photos of family, friends, and outfits.

But at the beginning of March, around two weeks before the coronavirus lockdowns started in the United States, Katie Simon, one of her followers, noticed an unusual post from Schroeder. “Randomly one day she popped up in my feed, talking about a spiritual awakening,” Simon said on the phone. “She was being vague and saying how she felt like shining light on this was her calling and she felt the need to use her voice and platform.”

Curious, Simon dug deeper. In Schroeder’s Instagram Highlights, which are Instagram stories selected by posters to stay up longer than the normal 24 hours, Simon found a set of messages titled “Theory.”

In the posts, Simon said, Schroeder “started going off on how Tom Hanks was a pedophile, and how he’s not actually quarantined, he’s under house arrest.” The posts discussed rampant child trafficking, and told followers that a “Great Awakening” was coming, using a QAnon community term describing the supposed impending mass arrests of elites liberal pedophiles. She also posted a link to an over two and a half-hour YouTube video about the “secret cabal” running the world.

Aghast and bemused, Simon posted screenshots of Schroeder’s hoaxes to her own Instagram story in early March, showing off its absurdity. Her followers starting responding, saying they too had seen more and more such theories start popping up on the pages of other influencers. The conversations kicked into high gear just a week or so after the lockdowns aimed at stopping the spread of coronavirus had started in the U.S.

Others noticed the trend. Azadeh Ghafari, a licensed psychotherapist who runs the.wellness.therapist Instagram account, observed that the alternative medicine, wellness, and pseudoscience communities she follows on the app were starting to share the same types of QAnon and fringe-right conspiracies. Accounts offered stories about elite cabals keeping children in tunnels underneath New York City, and how the coronavirus was either a part of a plot to save them, or a coverup to harm even more children.

“It’s unlike what I’ve looked at before. You would assume these hippies are progressives,” she recently told Mother Jones. “There is this faction of ultra-conservative, some Christian, mixed in with anti-vaxxers, mixed in with health and lifestyle folks.”

As these theories reach new audiences, Travis View, an independent conspiracy theory researcher who hosts the podcast QAnon Anonymous, says there’s been an uptick in the number of people coming to him to express concern about loved ones falling down the QAnon rabbit hole. “It was once or twice a month. Now in there are people in my [Twitter] DMs two or three times a week,” View says.

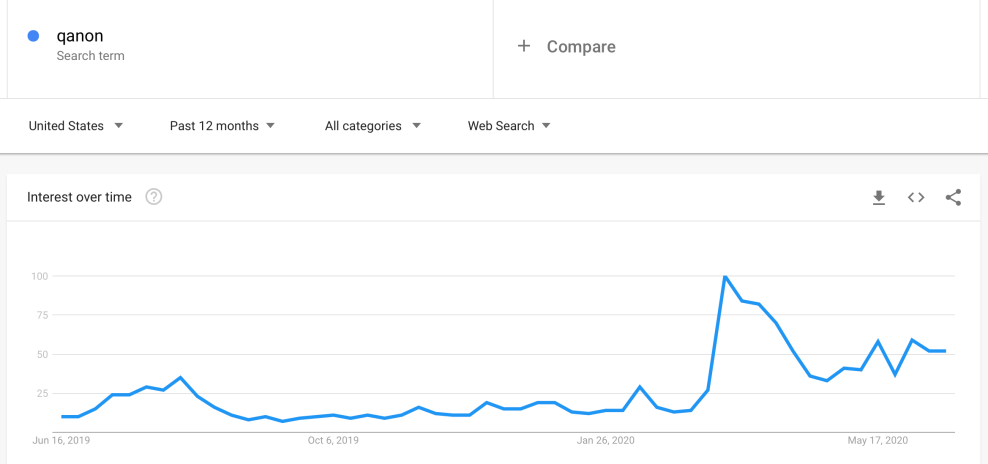

Data compiled from social networking sites and Google and Wikipedia search trends show a broader spike in interest around QAnon among Americans after businesses started to close and various lockdowns started in mid-March in anticipation of further viral spread. Online activity around QAnon and related topics rapidly climbed to all-time highs. Interest in the search terms has yet to return to pre-COVID levels.

Google Trends shows spikes in searches about the group, of its abbreviated motto “WWG1WGA” (where we go one, we go all), and for “adrenochrome” in line with the conspiracy’s belief that elites use the blood of children to create adrenochrome, a therapeutically injected chemical compound. The uptick in searches for such terms on Google and other platforms started around March 13, when US businesses started closing, and hit new peaks just a few days later on around the 17th, depending on the platform. Searches for WWG1WA had another peak around the beginning of June.

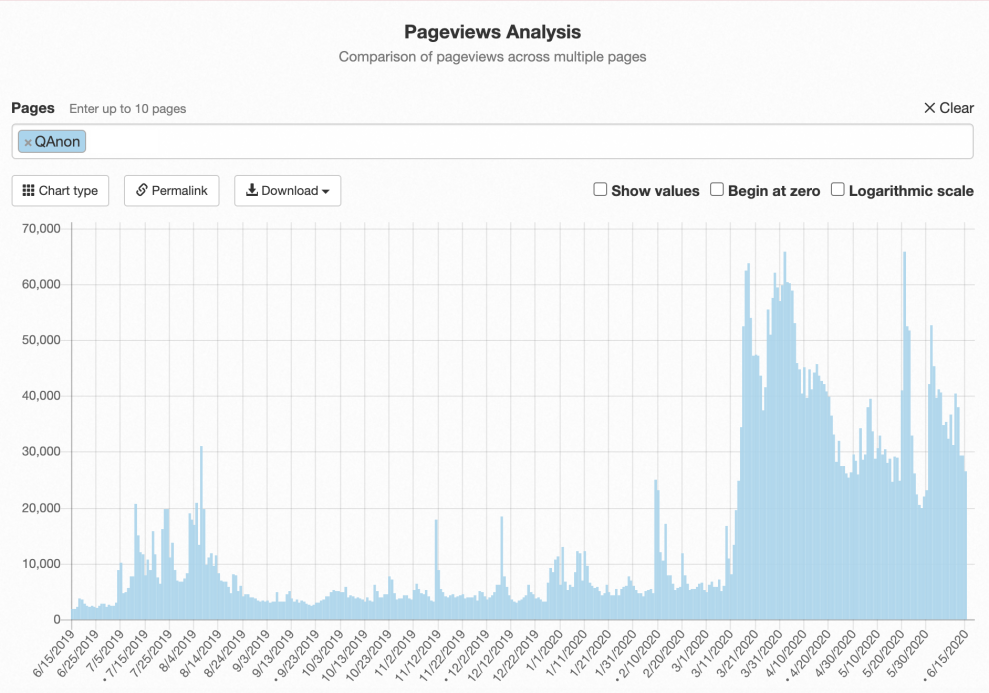

On Wikipedia, data tracking pageviews for “QAnon” and “adrenochrome” show nearly identical trends.

According to Wikipedia’s Pageview Analysis tool, views of the QAnon Wikipedia page started climbing on March 13, hitting 19,518 views in a day before reaching new peaks on March 18 and April 2 of roughly 65,000. Since that climb, views of the page haven’t dipped below 37,000 views—six times the previous average 2020 average of 6,000 daily views.

Adrenochrome page views on Wikipedia present an even more dramatic version of the same pattern. While daily views almost never went above 2,000 prior to March 13, they skyrocketed around March 17, hitting a new peak of over 56,000. Another dramatic peak of 77,888 came on April 5. That’s almost 40 times the average page views before the coronavirus broadly hit the US.

It’s unclear what generated a second, smaller spike in QAnon related searches at the end of May, however it could be the result of Q followers believing that George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the police was a false flag, faked for some reason.

A Mother Jones analysis of nearly 500,000 tweets posted across one week in April found that the average number of tweets per day using the hashtag #QAnon increased by 160 percent as compared to the averages compiled over six months of 2019 by the Twitter user @conspirator0 (Twitter later limited searches of posts on its platform, making other comparisons difficult.) The highest daily number of QAnon tweets documented by the account in 2019 was 75,349. After the onset of the US’s coronavirus crisis, that figure nearly doubled, reaching a high of 147, 748 tweets on April 4, 2020.

Anecdotal examples bolster what the data shows. Internet communities that hadn’t previously done so are now associating with far-right conspiracies like QAnon, impending mass arrests of elites for running pedophile rings, and liberal megadonor George Soros’s supposed plots. Across Instagram, pseudoscience wellness influencers, lifestyle influencers, anti-vaxxers, at least one contributor to Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop site, and other seemingly unrelated groups have all pivoted to spreading versions of these conspiracies that emerged on the far right.

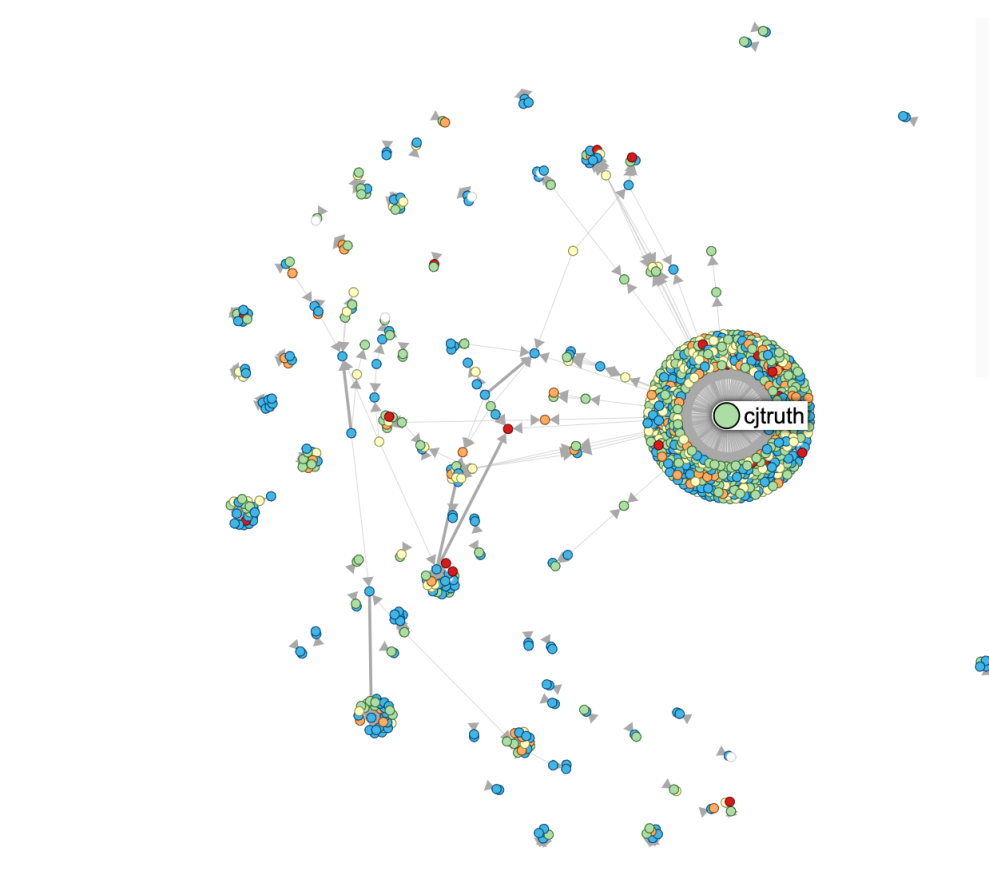

QAnon’s rise appears to have generated enthusiasm for the movement’s goals, including a persistent fringe right-wing push to fire the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director, Anthony Fauci, who is leading the Trump administration’s response to the disease, which reached an apex in mid-April when President Trump retweeted the #FireFauci hashtag. Q followers have actively not liked Fauci since at least March 21 when QAnon researcher Travis View noticed that they had turned on him for praising Hillary Clinton in an email from 2016 that was published by WikiLeaks. Their contribution in pushing #FireFauci is difficult to measure, and the movement has been boosted by anti-vaxxers and others outside of the Q universe. An analysis from Indiana University’s Hoaxy tool shows that cjtruth, a popular Qanon poster, was by the far and above largest disseminator of the hashtag the Saturday, April 18, following the president’s tweet.

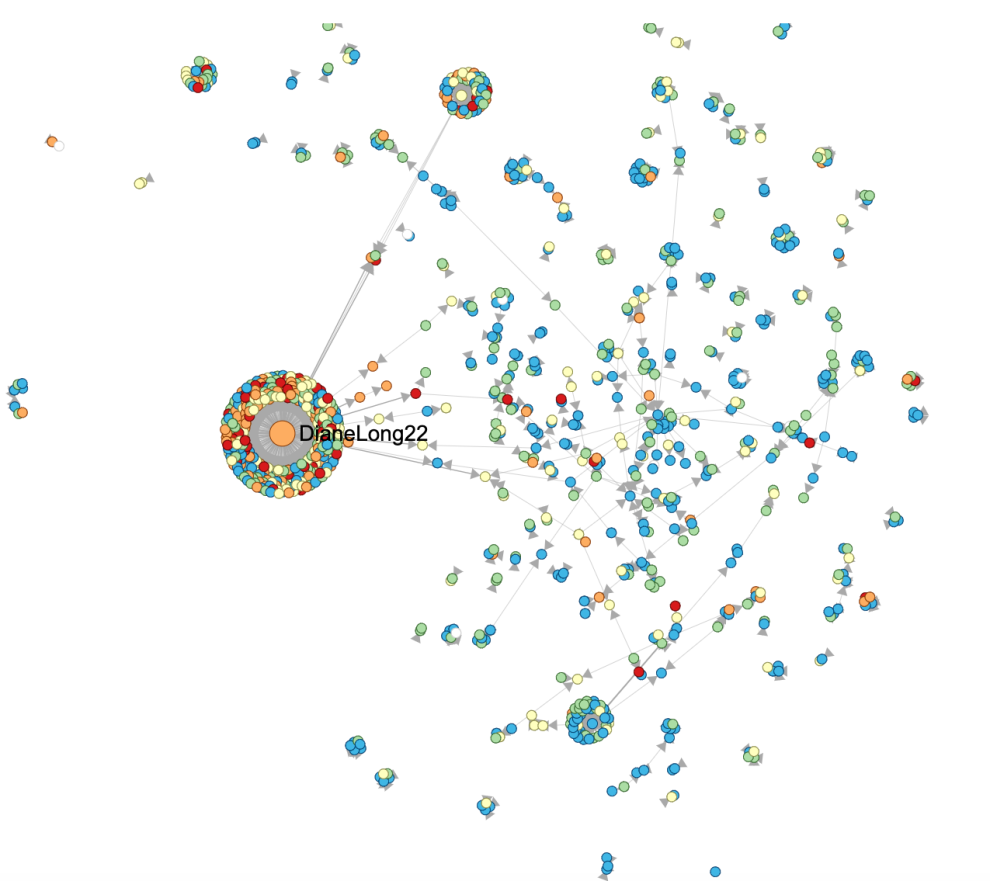

A June 16 search suggests that this may be a consistent trend. Most #FireFauci traffic around that date was driven by @DianLong22, another pro-QAnon poster.

Whitney Phillips, a professor of communication and rhetorical studies at Syracuse University who researches and writes about disinformation, explains that QAnon can be placed near one end of broader a spectrum of conspiratorial right-wing thinking. “QAnon is a piece of the puzzle, but you have to bring all the variables together that have brought us to this moment,” she said, noting that many on the right find QAnon to be too extreme, but, like Fox News host Sean Hannity and many other prominent conservatives, do believe that there is a deep state plot to undermine the president. Some won’t even use the term “deep state,” but will say that Democrats are engaged in a corrupt conspiracy to undermine the president and his allies. “It’s all different gradations of the same idea,” she said.

If any kind of political conspiracy ideation takes hold, Phillips said, ideas along the whole spectrum get a boost; QAnon benefits even when tepid, downstream conspiratorial thinking is pushed by more “normie” Republicans at places like Fox News, whose anchors famously downplayed the effects of coronavirus as a liberal plot to take down the president.

Schroeder, the Instagram influencer whose conspiratorial shift in posting habits raised questions for Simon, represents the phenomenon. Even though her posts contain language and themes that are prevalent in the pro-QAnon community, she told me over email that she “would not claim to be a full fledged follower of Q.”

“I became passionate about sex-trafficking recently and that is what pulled me into these ‘theories,’ Schroeder said. “There are some aspects of these theories that drew me in and as I researched, I felt there was some truth. Human trafficking is an issue regardless of who is doing the trafficking.”

View gave a simpler explanation for the QAnon’s rise amid the pandemic. “People are trying to make sense of the world during a trying time,” he said pointing to a study conducted at the University of Warsaw that found links between “high-anxiety” situations and conspiratorial thinking. While the paper found a link between stressful conditions and belief in anti-semitic conspiracies, it noted that a predisposition to anti-Jewish thought is often seeded before a high-stress situation.

In this case, the seeds for a broader turn to QAnon and other fringe-right wing conspiracies among more mainstream online and conservative communities were set long before the coronavirus by conspiracy mongering by the likes of Fox News and elected Republican officials. With the groundwork laid, the coronavirus seems to have set off a broader flight of fantasy.