This story was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering the US criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Twitter and Facebook.

One of the first things Tarra Simmons tells voters when asking for their support isn’t the prestigious fellowships she’s won or the legislation she’s helped write. It’s about the years she spent behind bars.

It’s a story Simmons, a candidate for state representative in Kitsap County, Washington, has shared at countless campaign events, which these days are entirely online: How she lost her car, her house, her nursing license, her voting rights. How after coming home in 2013, most of her minimum-wage paychecks from Burger King were taken to pay the $7,600 she owed in court fees. How she managed to climb out of that life, get a law degree and begin a civil rights nonprofit. And how all of it made her realize that only those who have lived through the system can fully understand how to fix it.

“I went to prison. It’s not something I’m proud of, but I understand how people end up there,” Simmons said at a May campaign fundraiser via Zoom, her digital background set to a generic corporate lobby. “Our criminal justice system is just a Band-Aid; I want to prevent [incarceration] from happening to begin with.”

Simmons is one of a new crop of political candidates in 2020 for whom being formerly incarcerated isn’t a disqualifier or a political liability. It’s an identity—one they say is vital to represent in state capitals and the hallways of Congress, as lawmakers try to overhaul a system that spends billions to lock up mostly Black and brown people.

The ongoing protests against racism and police violence, sparked by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, have highlighted the distance between two Americas: one that has lived under the pressure, surveillance and control of the justice system, and one that has not. It’s unacceptable, candidates say, for only people who have never been on the other side of law enforcement to write the laws that affect those who have.

Simmons, who identifies as white and Hispanic, speaks often of the disproportionate impact the criminal justice system has on people of color. “I am a mother of two Black sons and have been working on racial equity for nearly two decades,” Simmons wrote in a recent campaign email, “and I will be the first formerly incarcerated individual in our state legislature if we succeed in this election.” She has called for demilitarizing the police and reinvesting police funding into community programs.

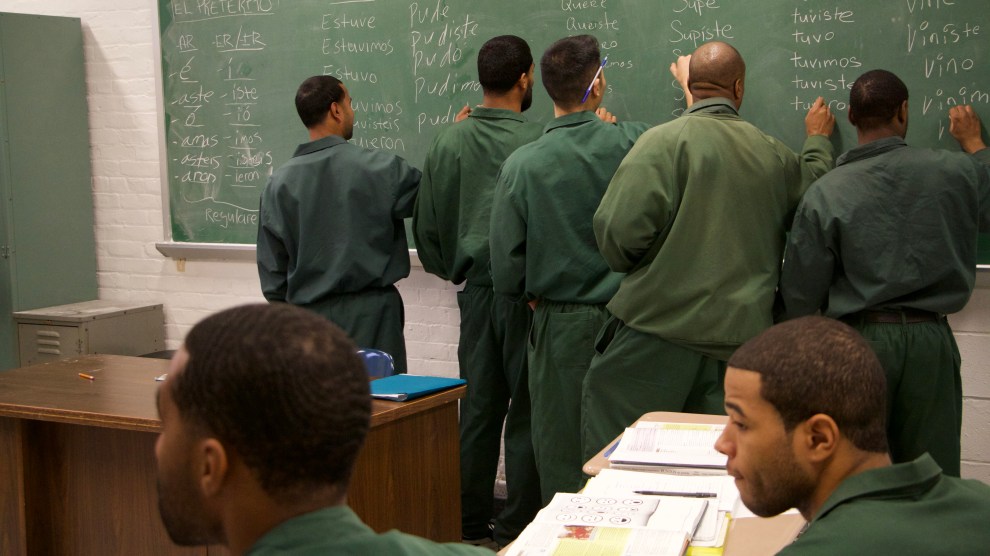

Kevin Harris is running for state representative in Detroit, Michigan, where he recently served as the departing representative’s legislative director. He came home from a 14-year sentence in 2006 and soon got involved in community organizing. He was 18 when he went to prison. “It was the height of the crack epidemic. I had a little bit of a political awakening in understanding how the Department of Corrections treated people,” he said. “It’s not a coincidence that so many people from the Black community have criminal records. We’ve been targeted—we’ve always been targeted.”

Rachel Elise Thomas for The Marshall Project

Now, Harris said, it’s even more important to talk about his experience in prison. As a Black formerly incarcerated organizer working on criminal justice, voters know he’s been “in that fight” long before George Floyd was killed. Now is his moment, he said. “I’ve got to get to this place so my voice is elevated, so I have a bigger bullhorn,” he said of the state legislature. “One-third of all Americans have some kind of criminal record. Almost every family has been touched by it.”

There has been a dramatic shift in the criminal justice conversation in recent years. A majority of voters from both parties now say they would be more likely to vote for a candidate “who supports criminal justice reform.” And whether people leaving—or still in—prison can vote received unprecedented attention in the Democratic primary race. But voters rarely hear from candidates who have firsthand experience with the justice system.

Several formerly incarcerated candidates stressed that their platforms weren’t solely about prison reform, especially amid catastrophic public health and economic crises. “I had to become more of an intersectional candidate, to respond to what my community needs,” said Simmons, who at recent meetings talked about everything from how political districts are drawn to protecting habitats for salmon.

But she hopes her message of decarceration is more timely than ever. “We’re going to have more momentum, especially if we can ground it in a health and economic argument … Incarceration costs us a lot of money.”

Making it into the room where it happens will still not be easy. Fundraising for first-time candidates is a particular challenge with door-knocking on hold and in-person events cancelled because of the pandemic. And, like many other parts of civic life for those with felony convictions, serving in government is restricted by thousands of state-level laws. Multiple states—such as Illinois, Alabama, and Delaware—ban people with criminal convictions from holding most public offices. Others, like West Virginia, outlaw it after certain crimes, like bribery, or bar people for multiple years after their release. These laws disproportionately keep people of color, who are more likely to be sent to prison, out of public office.

If someone is legally able to run, the stigma of incarceration can still be a deterrent. Even Simmons—who was convicted of a lower-level drug offense in a liberal state—has faced significant blowback. In 2018, a conservative political action committee used her story in a smear campaign against one of her supporters, Washington state senator Emily Randall. Randall had recently posted on Facebook, cheering Simmons’ bid to become a licensed attorney. The mailers against her read: “TOO SOFT ON CRIME … Randall has supported Tarra Simmons, a drug-addicted ex-con.”

To Simmons’ surprise, the ads sparked a statewide backlash. The chair of the Washington state Republican Party called to apologize. It made Simmons think voters might be ready for a formerly incarcerated candidate. When state senator Sherry Appleton, the 16-year Democratic incumbent, encouraged Simmons to run for her seat, Simmons agreed. Kitsap County prosecutor Chad Enright, who leads the same office that sent Simmons to prison, has also endorsed her.

But in news coverage of her candidacy, Simmons has had to deal with headlines calling her “ex-inmate” or stories that list her criminal conviction as one of the only details.

“There’s a missing voice in our legislature,” Simmons said. “You have a lot of well-intentioned advocates who are trying to push criminal justice reform, but they can’t know it as intimately as people who have survived it.”

“Survived” is the right word to describe Simmons’ early life. As is true for most women who end up in prison, she was the victim of serious crime long before she was the perpetrator. Growing up in Bremerton, across the Puget Sound from Seattle, Simmons said most members of her immediate family dealt with addiction. Most had served time. No one graduated high school. Simmons ran away from home and by 14, had lived through foster care, juvenile detention, homelessness, sexual assault and trafficking. At 15 she had her first child.

His birth marked a new chapter for Simmons, connecting her with social services and prompting her to enroll in an alternative high school. As a single mother, she worked her way through high school, college and nursing school, eventually getting a steady job as an E.R. nurse. She had a second child.

But a series of events resurfaced Simmons’ childhood trauma. A spinal injury led to a painkiller prescription, which led to an opioid addiction. Her addictions spiraled into drug dealing, and soon she was facing criminal charges for theft, drugs and gun possession. In 2011, a judge sentenced her to 20 months in prison.

Andi Buescher

Simmons began substance abuse treatment while incarcerated. When volunteer law students helped her file a motion to maintain custody of her kids, she started thinking about applying to law school herself. Simmons wanted to fight the avalanche of civil legal consequences that came with her criminal conviction: a house in foreclosure, the loss of her nursing license, her car repossessed.

“People only associate me with my incarceration history, not the tremendous amount of violence I’ve survived,” Simmons said. “I had a really hard time trusting people. Meeting these volunteers made me believe I could heal.”

After her release in 2013, Simmons enrolled at Seattle University School of Law. She graduated with honors and won a prestigious Skadden Fellowship for recent grads working in public interest law. Governor Jay Inslee appointed her to lead a new statewide reentry council. But her own criminal history would yet again get in the way.

The “character and fitness board” of the Washington State Bar Association wouldn’t let her take the exam required to be a licensed lawyer, claiming that she minimized her drug abuse in her application. “[S]ome of the attitudes she expressed in the record and at the hearing signal that her acquired fame has nurtured not integrity and honesty, but a sense of entitlement to privileges and recognition beyond the reach of others,” board members wrote.

Simmons enlisted her friend and mentor Shon Hopwood—another formerly incarcerated attorney and Georgetown Law professor—and appealed the decision to the state’s highest court.

“They let someone with five armed bank robberies into the bar,” Hopwood said, referring to himself. “Losing my shit is the nicest way to describe how I felt. There are few people on this planet who have overcome the things that she has.”

The Washington State Supreme Court handed back a unanimous decision the same day they heard arguments. She won.

Simmons is now the founder and executive director of Civil Survival Project, a nonprofit focused on reducing barriers for people coming home from prison and involving them in policy-making. The group has been pushing for legislation to automatically restore voting rights for people leaving prison and to expunge certain criminal records.

Many supporters who attend Simmons’ campaign events carry the invisible burden of a criminal record, and know intimately the innumerable, byzantine obstacles it creates.

“I couldn’t get life insurance because I have a felony,” said Woodean Nickerson, a social work student, over appetizers at Simmons’ campaign launch in January.

“I couldn’t get a job,” said Andre Henderson, a college student who, despite great grades, was initially denied a work-study position. When the community college told him they had to run a background check, “it was like I was being policed and patted down all over again. It’s traumatizing,” he said.

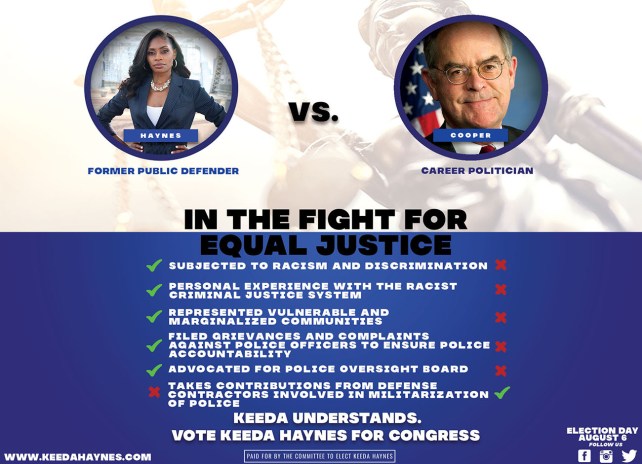

A felony curtails involvement in civic life, too. Keeda Haynes, a former public defender who served nearly four years in federal prison in 2006, is currently running for Congress in Nashville, Tennessee. But she could not run for local office or even sit on a jury until she petitioned a court to restore her civil rights—a legal process that can be difficult to navigate. “This is an opportunity to change the narrative and have tough hard conversations around barriers to reentry,” she said of her campaign. In a recent mailer comparing her record on racial justice to her opponent’s, Haynes noted her “personal experience with the racist criminal justice system.”

Courtesy Keeda Haynes

Candidates say that experience is invaluable in shaping policy. “There’s a huge difference between wisdom and education. Education is what you learn from books. Wisdom is what you learn from your own life,” said Angela Stanton-King, who is running as a Republican for Congress in Georgia’s 5th District, against longtime civil rights leader and Rep. John Lewis. She has been a vocal supporter of Donald Trump and law enforcement during the ongoing protests for racial justice.

Stanton-King served over two years in federal prison. She says being shackled while giving birth prompted her to push for a federal ban on the practice. Unlike many Republicans, she supports the right to vote for anyone with a felony conviction once they leave prison. “I’m here to dispel the saying, ‘once a felon always a felon.’ That’s not true,” she said.

The countdown is on to August’s Democratic primary for state races in Washington. As the pandemic continues, Simmons has increased online events and phone banking—which her campaign has also been using to connect vulnerable constituents with resources during the shutdown.

So far, Simmons has raised over $165,000, a little over $20,000 of which came from a January fundraiser in New York City, hosted by several national criminal justice advocates, records show. (The organizers included a member of The Marshall Project‘s board of directors.) Her main opponent in the primary is Leslie Daugs, a current Bremerton City Council member, who has raised a little more than $20,000.

Election day will be the true litmus test for voters. “The same way we ask the question is the ‘U.S. ready for a female president?’—are we ready for a U.S. representative that has a felony on their record?” asked Haynes, the Tennessee candidate challenging incumbent Jim Cooper in that state’s 5th congressional district. “I would like to think the answer is yes, but we will see. I don’t think that’s going to be the deciding factor.”

In her campaign for Congress in Maryland, Mckayla Wilkes spoke openly about her experience in juvenile detention and a brief stint in jail while pregnant, for driving with a suspended license. She lost in the primary on June 2, against long-time incumbent Rep. Steny Hoyer. “I never thought that someone formerly incarcerated like myself would even be taken seriously,” she tweeted. “We lost. But it does appear we won more votes than any primary challenger to Hoyer in 40 years.”

Regardless of election results, just seeing people speak openly about their criminal record is a turning point for some. Kelly Olson, an Olympia, Washington, organizer with the Civil Survival Project, attended one of Simmons’ early campaign events in December. For the first several years after she came home from prison in 2007, Olson didn’t share her past unless absolutely necessary—including during an internship at the Washington state senate. It was only after she met Simmons that she “came out” as formerly incarcerated.

“I was holding my own life back, it was my own internal shame. It’s so important for people to see us as humans, to see we’re capable of leadership,” Olson said. “Seeing Tarra do it [makes me] realize our stories do matter. I wish I had come out sooner.”