Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Chances are, you already don’t trust the police. Polls show that most Americans don’t.

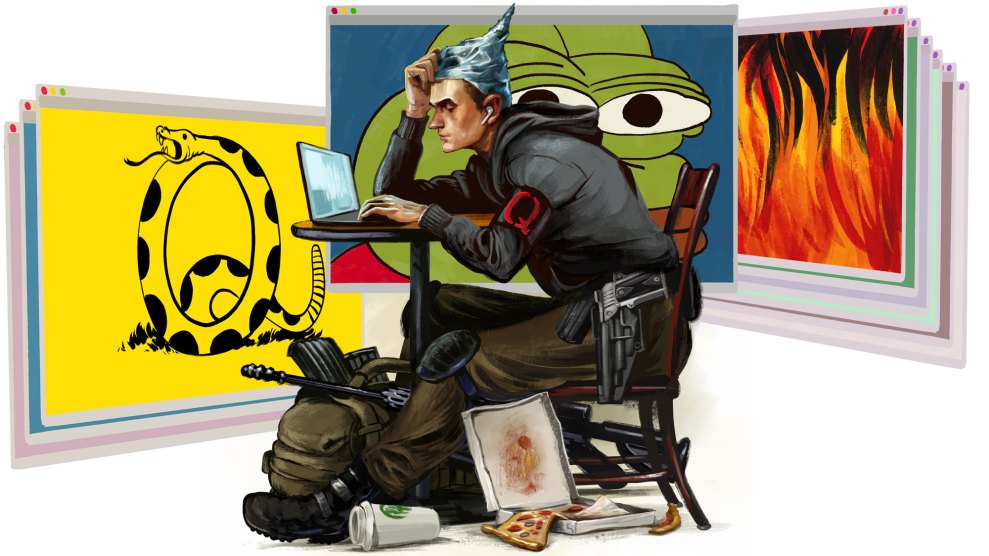

But what if the cop patrolling your neighborhood held bizarre and unsubstantiated views? What if there was a chance that officer in the patrol car idling down the block was watching videos about a conspiracy holding that a satanic cabal of high-profile liberal pedophiles is running the world’s most insidious sex ring? Or was swiping through memes popularizing a made-up plot about kidnapped children kept in underground tunnels so their blood can be harvested to help keep wealthy people alive? And what if they sincerely believed it all?

In a small but growing number of places across the country, that’s just what is happening, as police officers have endorsed QAnon, the overarching conspiracy theory comprising these beliefs.

Nico Roche, an officer in Bellevue, Washington, was put on administrative leave early this summer after it was found that he violated the department’s social media policies for, among other things, posting a picture of himself in riot gear labeled with the QAnon hashtag #WWG1WGA, an abbreviation of the popular Q slogan “Where We Go One, We Go All.”

Up until he retired from the New Haven Police Department in early September, Jason Bandy was perhaps the policing world’s most aggressive supporter of QAnon. Bandy, who owns a pre-workout vape business, sometimes wears basketball jerseys that show off the full-sleeve tattoos the cover both his arms and his neck while recording episodes of his podcast For The Love, which covers QAnon among a range of other conspiracies.

Many of Bandy’s recordings sound like far-out internet ad-libs as he and his guests, do hazy, freeform opining anything from adrenochrome—a therapeutic compound that the hoax baselessly holds is acquired from children’s blood—to liberal financier George Soros controlling society, a thinly veiled anti-Semitic conspiracy.

“These elites are torturing these kids,” Bandy said in a March episode of For The Love, as reported by the New Haven Independent. “Yes, there’s sex involved. They’re trafficking these children and all these other rituals that they do. They are Satanic worshipers. They are Illuminati, deep state, all this.”

Matthew Kunkel and Mark Manicki, both police officers in La Salle, Illinois, had their support for QAnon become known after one of them posted pictures of the duo wearing vests emblazoned with “Q” at a rally to end coronavirus lockdowns and reopen the economy. La Salle Mayor Jeff Grove told the Times, a local paper, that the city would investigate the incident, but that in his view, “what you do on your own time is your choice, and that’s your right.”

Manicki was even more nonplussed by having his support of QAnon become a topic of controversy. “I, like millions of other people on this planet, enjoy the challenge of attempting to decode the information contained within the Q drops. It’s called ‘Q Research’ for a reason, it requires research to obtain the information encoded within the posts,” Manicki explained to the Times. “I’m merely someone who sits on my couch late at night with my dog on my lap, iPhone in hand, while seeking the truth. Last time I checked, there was nothing wrong with that!” (La Salle police did not return a Mother Jones request for comment.)

Like LaSalle’s mayor, some people in power who have been asked to answer for QAnon supporters in their proximity have acted as if the conspiracy is ultimately harmless. But this is a dangerous misconception, especially when it comes to government agents empowered to use force. The logic of the conspiracy theory almost requires its adherents to carry out acts of violence: If you actually believe that elites are harboring scores of children in underground tunnels to rape and steal blood from, taking action to liberate them would be a moral imperative.

QAnon supporters at least partially motivated by their belief in the conspiracy theory have plotted to carry out fatal, violent acts, or actually done so. In a deep irony, QAnon supporters have actually kidnapped children. The FBI has warned about the potential dangers of QAnon adherents carrying out violence in a document that is designed to be distributed to local law enforcement agencies.

QAnon supporters committing outright crimes, while concerning, is rare. What’s more common and still destructive is QAnon adherents’ tendency to target and relentlessly harass people. Terrorizing people online is a way for QAnon supporters to feel like they’ve done their part without physical risk or likely breaking the law.

“What’s a lot more concerning than targeted harassment though,” warns Travis View, “is someone with of the power of a police officer taking action on someone.”

View produces the podcast QAnon Anonymous, which recently featured an episode on “QAnon Cops.” I spoke to him on Zoom call along with his co-host Jake Rockatansky.

“The danger,” Rockatansky added, “is that you’ve got law enforcement who have a tremendous amount of responsibility who are showing complete disconnect from reality. They carry weapons. What happens if a police officer thinks that they’ve uncovered a pedophile ring?”

It might have been inevitable that QAnon would find an audience among police officers; the conspiracy’s adherents, like cops, decidedly skew Republican. In June, Jesselyn Cook and Nick Robins-Early wrote for the Huffington Post about how Law Enforcement Today, a website and podcast platform that claims to be the largest law enforcement-owned and operated media outlet, has pushed authoritarian politics and far-right conspiracy theories to its audience. Though the site hasn’t explicitly backed QAnon, it has endorsed the pro-QAnon politician Marjorie Taylor Green, and has embedded tweets bearing QAnon hashtags in at least a dozen stories.

Police officers have a history of believing lurid conspiracy theories about child endangerment—conspiracies that have repeatedly arisen on the right at times of progressive gains. In 1991, Robert D. Hicks, an academic working as a law enforcement specialist with the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services, published his research detailing how cops bought into some of the most farcical allegations of the satanic panic of the 1980s. His book, In Pursuit of Satan: The Police and the Occult, documents how law enforcement put credence in elaborate tales purporting satanic abuse at daycare centers. In one story spread by a Virginia investigator, children were supposedly bussed to an airfield, flown to a ceremonial site for ritual abuse, then put on a return flight and bussed back to the daycare in time for unsuspecting parents to pick them up. In another, police arrested two brothers that had supposedly got a voodoo priest to cast a death spell on a judge. The brothers were charged with conspiracy to commit murder, on the basis of the hex.

Jamie Longazel, an associate professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is at work on a book on the Blue Lives Matter movement, and the police culture undergirding it. He thinks one reason QAnon may be particularly alluring to cops now is that they face growing criticism from the left—which QAnon labels as evil pedophile enablers—while being embraced by the right.

Aside from that, Longazel says police are generally likelier to believe in conspiracies, pointing to the santanic panic era, and to a study he recently came across from 1964 that found exceptionally high police membership in the the John Birch Society, the influential far-right conspiracy group. As many as three percent of all members were police officers, according to the study.

Longazel says the the beliefs embedded within policing encourage such thinking. “They sort of operate on myth and fantasy on a day to day basis,” he explains. “At any minute someone is going to do some harm. And there’s this myth that police are the one way to control crime.”

More broadly, police officers and departments, who are used to operating with unchecked power, have a history of spreading information that comports with their world views, but not necessarily reality. In just the past several years, police have pushed multiple fabricated stories just about dairy products, spreading false stories about how milkshakes and frappucinos were involved in nonexistent plots to injure them—a milk-based mini-conspiracy of sorts. Some police have also pushed lactose-free misinformation about antifa supposedly traveling to suburban communities to riot, which is a full-blown conspiracy theory.

QAnon Anonymous has documented other cops falling into QAnon. One is Sgt. Dustin Schultz, an officer in the Moore, Oklahoma, police department and a prolific Tik-Toker who has posted at least two videos in support of QAnon that include hashtags like #WWG1WGA.

In one, Schultz wonders why he hasn’t seen “celebs and some powerful people” speaking out on Q dispite the conspiracy’s popularity on Tik-Tok, as he floridly lowers sunglasses and raises his eyebrows at the camera, over notes of the Eurythmics’ “Sweet Dreams.”

Another officer in Jacksonville’s sheriff’s office posted a now-deleted Tik-Tok video that’s been preserved by QAnon Anonymous showing herself crying in uniform, in her police car, seemingly on duty, saying she’s just watched a QAnon YouTube video that falsely claims to unveil the secrets of the liberal cabal’s child pedophile ring.

QAnon believers can also be found on Thee Rant, a web forum that requires members to verify they are current or former New York Police Department officers before posting. “This Q posts anonymously on web boards and has been proven right on many posts yet he is considered some crazy wacko,” one poster explained back in 2018. “He is just a source like any other but he is accurate and consistent.”

“I’ve posted here before about the counter-coup that petitioned Trump to run to counter the Obama/Clinton/Globalist takeover,” another Thee Rant user with a history of posting on QAnon and Q-adjacent conspiracies wrote in 2020 thread. Others responded with pro-QAnon posts.

NYPD appreciation of QAnon goes beyond the rank-and-file. In July, the head of the NYPD sergeants union, Ed Mullins, appeared on Fox News with a QAnon mug in the background, which he had apparently done multiple times before.

These public expressions could just be the visible tip of a larger iceberg of less visible support for QAnon from law enforcement contingent, including from officers worried about repercussions and savvy enough to keep their conspiratorial politics to themselves. In what served as a relatively early sign of police warming to QAnon, in 2018, Mike Pence’s social media team shared a photograph showing him greeting Florida SWAT team members including Matt Patten, an officer in the Broward County sheriff’s office, who was wearing a QAnon patch. After the photo came to attention, the department said he was disciplined.

“For every QAnon cop who is dumb enough to just post ‘Yes, I love Q. Where we go one, we go all,’ there’s got to be many more who are better at hiding their power level,” View said on his podcast. “Who perhaps understand how this might potentially put their career in jeopardy if they’re totally open about this shit.”