At four o’clock on a Thursday afternoon, the lobby of Dragonfly Wellness is almost completely full. Clients perch expectantly on the sofas, waiting to be buzzed through the locked door marked PATIENTS ONLY. This might not be an unusual scene elsewhere—medical marijuana is legal in more than 30 states—but this happens to be Salt Lake City, within blocks of both the Utah state Capitol and the main temple of the Mormon Church, which proscribes consuming virtually any substance more potent than Diet Coke.

Utah might be the last place you would expect to find any kind of cannabis, but in 2018 Utah voters approved Proposition 2, a ballot measure legalizing medical marijuana, despite huge opposition from the Mormon Church and the conservative state legislature. Two years later, it’s clear that Prop 2 has had a much wider effect than merely legalizing medical weed; it’s begun to shake up one of the most entrenched and tone-deaf GOP legislative supermajorities in Red America.

Consider this: Utah voters not only approved medical marijuana in 2018, they also passed ballot measures calling for Medicaid expansion and independent redistricting, two major progressive priorities. This in a state where Republican candidates routinely clobber Democrats by 30 percentage points or more in statewide races. Although the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS) and the Republican establishment fought all three measures—Proposition 2 in particular—many good Republicans and Mormons clearly voted for all three of these “liberal” laws, in defiance of church and party.

“We have districts where Republicans won by a large majority, but the ballot initiatives passed,” says Rebecca Chavez-Houck, a former state representative who helped implement Proposition 4, which established an independent redistricting commission. “These were specific initiatives on issues that [the legislature] had voted against, year after year after year. So you have Republicans who feel like their representatives are not aligned with them on these issues.”

That’s a nice way of saying that Utah is in the middle of a voter rebellion, driven by a growing gulf between what people actually want (marijuana, Medicaid, and fair districts) and what their conservative, religious elected representatives have been willing to give them.

It happened again in December 2019, after the state legislature passed a sweeping tax reform package it had spent several months crafting. The main thrust of the “reform” was to cut the state income tax rate while increasing the state sales tax on groceries, and imposing new sales taxes on certain everyday services, such as dog grooming. This was so transparently rigged to benefit the rich at the expense of everyone else that even Utah’s generally Republican voters rebelled. Within weeks, organizers on both the left and the right had gathered more than enough signatures to compel a ballot measure repealing the tax “reform.” The legislature folded immediately and repealed the bill it had just passed.

“It was an incredible exercise of the people’s power,” says Chavez-Houck, a Democrat. And to many, it was a harbinger of change to come.

Everybody thinks of Utah as a rock-ribbed red state. After all, although many Mormons view him with distaste, Donald Trump recently carried it by 20 points. But Utah is also a very confused state right now. Thanks to an influx of newcomers from California and the East Coast (like me three years ago), drawn by jobs in the booming local tech industry and the outdoor lifestyle, Utah today is starting to demographically resemble its bluish-to-purple neighbors Arizona, Nevada, and even Colorado. A Gallup poll ranked Salt Lake City among the 10 gayest cities in America. And voters—especially young voters—are less wedded to the doctrines of the Mormon Church than in the past. Yet political power remains tightly gripped by a small group of very right-wing, very religious Republicans who have controlled all three branches of state government for more than three decades—and show no signs of letting go.

Utah isn’t the only place that’s chafing under a conservative legislature. In Pennsylvania, a majority of registered Democrats live under often vindictive GOP legislative rule; most recently, Pennsylvania’s Republicans went to the US Supreme Court to stop these Democrats from mail-in voting. (They lost.) In Texas, the electorate is being pulled to the middle by demographic change, while the legislature remains regressively conservative. But Utah is 78 percent white and overwhelmingly Republican. It is still a place where a woman can face criminal charges for going topless in her own home. Yet it is precisely these white Republicans who are beginning to join Democrats and rebel against their own politicians—in one ballot-measure fight after another. Even Republicans are getting sick of Republican rule. And Utah offers a blueprint for how to liberate your state from one-party rule.

“Again and again in the last few years, we’ve seen the public rise up against the legislature,” says Rep. Joel Briscoe, a veteran statehouse Democrat from Salt Lake City.

The governing class is not pleased about having to answer to voters’ wrath. In his opening remarks at this past January’s 45-day legislative session, House Speaker Brad Wilson blasted the ballot propositions as “divisive” and “ruinous,” accusing voters who supported them of having “turned away from the basic principles of a democratic republic.”

But that charge is more accurately leveled against the legislature itself, where Republicans exert supermajority control. “Everything is decided in closed Republican caucuses and closed back rooms, with the governor and the legislature,” says former Democratic state Sen. Jim Dabakis. “When that happens generationally, and there’s no checks and no balance and nobody is allowed to delve into the details of government, you get a very arrogant, very entitled, very out-of-touch group governing.”

“You really do have a dictatorship of the legislature in this state,” says political consultant Reed Galen, a co-founder of the Lincoln Project who helped support the redistricting initiative. The ballot measures raise a simple question: How much longer can this go on?

Key to understanding Utah’s confusion is that its legislature is more religious and hardline than the state itself, and the gulf continues to widen. For starters, about 60 percent of Utah’s population is nominally Mormon—a figure that has been steadily declining—while more than 90 percent of state legislators are active members of the LDS Church (including a handful of Democrats).

The party balance is also out of whack: Democratic candidates typically pull 30 to 40 percent of the vote statewide but hold only 21 percent of legislative seats. The six Senate Democrats could caucus around a lunch table. Twenty-five of the 104 legislators are women—representing an all-time high—but only three are Latino, although Hispanics and Latinos make up 15 percent of the state’s population, and the number is growing.

The typical Utah legislator is thus a wealthyish white businessman who generally works in real estate, accounting, or insurance (the legislature is part time), is a diehard social conservative, and is devoutly Mormon. “The legislature is a lot more conservative than normal Utahns,” says Lauren Simpson, policy director for the Alliance for a Better Utah, a left-leaning watchdog group.

There are structural reasons that explain why the legislature is so extreme, Simpson says. Because both parties have traditionally chosen candidates in party conventions, GOP candidates must pass muster with far-right activists, such as Gayle Ruzicka, a Phyllis Schlafly disciple who heads the Utah chapter of Eagle Forum, which enforces strict discipline on social issues such as abortion and LGBTQ rights. More recent changes to election law—which the state GOP strenuously opposed—allow candidates not chosen in their parties’ conventions to force a primary by gathering signatures, a strategy since employed by outsiders such as (checks notes) Sen. Mitt Romney.

But thanks to artful gerrymandering, voting in a general election has felt almost irrelevant. Liberal, gay-friendly Salt Lake City and its moderate suburbs are split among the four congressional districts. My Salt Lake neighborhood shares Rep. Chris Stewart, a leading Trump toady, with the Sunbelt retirement mecca of St. George, 300 miles to the southwest. Republicans claimed they drew the legislative map to “balance” urban, suburban, and rural voters in each district to reflect the geographic makeup of the state.

“They didn’t really believe that,” says Matthew Burbank, professor of political science at the University of Utah. “All they really wanted to do was dilute the impact of people in Salt Lake City so they wouldn’t have a voice in Congress. That was very purposely done.”

The same thing happens at the statehouse level: Democratic and non-LDS enclaves such as greater Park City and Moab are sliced up like pizzas. The result is a lack of meaningful competition. “People are forced to choose between whatever the Democrats come up with against a Republican who may be substantially more conservative than the district. There are no other options,” says Michael Lyons, a professor of political science at Utah State University. “The real-world consequence is that we have an unrepresentative state government.”

Republican co-sponsor Rep. Brad Daw speaks on the floor of the Utah House of Representatives before a vote on medical marijuana in September 2019.

Rick Bowmer/AP

On a Thursday afternoon in mid-March, the House is taking a break—or, in quaint Capitol parlance, “sauntering.” The chamber door opens, and representatives amble out into the blindingly marbled atrium, where a small army of blue-suited lobbyists awaits. There are lots of short haircuts and ex-high-school-football-player physiques; the few women wear sensible suits.

A bell sounds, and they saunter back into the chamber and take their seats. The 16 Democrats are crammed into the right rear corner, like an outnumbered battalion making a desperate last stand. Their 59 Republican colleagues look more comfortable; one is sitting with his feet up on his desk, flossing. A ceiling mural depicts the famous first vote cast by a Utahn woman, Seraph Young, in Salt Lake City in 1870. Utahns pride themselves on having granted women the right to vote 50 years before the federal government. But you wouldn’t know it from the proceedings; already this session, the Equal Rights Amendment has been deemed dead on arrival.

With the affable manner of a fraternity president, Speaker Brad Wilson opens discussion on a bill that would almost completely ban abortion in the state. Doubling down on an 18-week abortion ban that the legislature passed just a year ago, this bill is biblically harsh, classifying abortion as a felony for the patient or anyone who ends their own pregnancy, with up to 15 years in prison and a $10,000 fine for those convicted. Exceptions for rape, incest, a nonviable fetus, and risk of the woman’s death or long-term impairment exist, but are hard to get: Not just one but two physicians would need to attest that a fetus is not viable before one could be granted.

Meanwhile, the 18-week ban remains tied up in court; attorneys for the legislature estimate that defending the bill all the way to the US Supreme Court could cost the state between $1 million and $3 million. To avoid another costly legal fight, the total abortion ban would take effect only if (or perhaps when) the Supreme Court overrules Roe v. Wade. Various Democrats try to soften the bill with amendments, but they all fail and the bill passes easily.

Year after year, abortion dominates the legislative agenda, despite a recent poll conducted by the ACLU and Planned Parenthood indicating that 80 percent of Utahns feel that abortion is already sufficiently or overly restricted in the state. There is a macabre measure that would mandate burial or cremation of fetal remains, and another requiring any woman seeking an abortion to undergo an ultrasound exam, during which her provider would be compelled to describe the developing fetus in detail and play audio of the fetal heartbeat. When members of the Senate return from a saunter to debate this particular bill, they are confronted by an enormous photograph of an ultrasound wand, phallic and menacing. Things are about to get uncomfortable.

Leading the opposition is Sen. Luz Escamilla, an outspoken Democrat who had already tried to amend the 18-week abortion ban to prohibit masturbation as a needless waste of potential human lives. One by one, she and her five female Senate colleagues—including two Republicans—rise to speak against the bill. “I’ve always been pro-life, but sometimes we go too far,” admits Sen. Deidre Henderson, the Republican lieutenant governor–elect. When the vote is called, the women walk out en masse.

The bill passes the Senate anyway—like Democrats, women of both parties are procedurally irrelevant on Utah’s Capitol Hill—but a couple of days later, in the waning hours of the session, it simply vanishes. It needs one last procedural vote in the House, but time expires before it can come up again. For Utah Democrats, this is what passes for a victory: small, symbolic, mildly satisfying, but no more consequential than a rock tossed into the Colorado River.

While Democrats fight lost causes and doomed rear-guard actions, members of the GOP supermajority enjoy a pretty sweet gig. The part-time job pays $285 per day for the 45-day legislative session, which runs from late January through mid-March, and the stress is generally low. With so few Democrats, gridlock is not a problem. And fundraising is a breeze: Utah state legislators receive more than 93 percent of their contributions from corporations and special interest groups, according to an analysis by the Salt Lake Tribune. There is little need to court actual voters.

One of the most prolific political donors is a Utah-based multinational company called EnergySolutions, which operates a landfill for low-level Class A radioactive waste from domestic nuclear facilities in the desert west of Salt Lake City. In 2018, EnergySolutions successfully petitioned the legislature to partly absorb the costs of its state-mandated inspections, to the tune of $1.7 million a year. Previously, the company had been required to foot the whole bill. That amounted to a spectacular return on EnergySolutions’ $67,700 in contributions to Utah lawmakers the previous year.

In 2019, EnergySolutions came back with a bigger ask (after committing close to another $45K in campaign money): It wanted permission to accept Class B and C waste as well—including depleted uranium that becomes more radioactive for tens of thousands of years. The state had previously denied such a permit, but the legislature passed a bill essentially allowing this waste to be buried within a 90-minute drive of the majority of the state’s 3.2 million residents. (That plan was eventually derailed, but the idea is far from dead, advocates say.)

Tax breaks and incentives are the currency of the realm. A dozen years ago, the state’s graduated income tax was replaced by a flat-rate tax, effectively granting a tax cut to the wealthiest residents. This also created a revenue imbalance that the legislature tried and failed to correct last year with its tax “reform” bill, which would have raised taxes on groceries and services.

Every session now features a parade of perks offered to favored industries. A recent big winner was Facebook, which will reap up to $750 million in state and local tax “incentives” for building a data center in the desert that will employ just a few dozen people. Did the state benefit? There is no way to tell, says Rep. Briscoe, because the legislature does not do cost-benefit analyses on most of the tax breaks it hands out. “It’s magical thinking. Shazam, it’s a tax break so it brings jobs,” he says. “But how do we know?”

Once granted, tax cuts are extremely difficult to claw back. When the legislature reconvened last spring to deal with the revenue shortfall caused by the pandemic, Briscoe proposed rolling back the $1.7 million EnergySolutions tax break, but that went nowhere. Instead, the legislature cut health and dental clinics serving the underinsured, among other social programs.

Sometimes these tax breaks are precisely targeted. In 2016, before he became speaker, Rep. Brad Wilson sponsored a bill that exempted foreign-earned income from state taxation. Seems reasonable. The catch, however, was that Wilson’s Taxation of Foreign Income Amendments did not apply to all foreign income, only to that earned from one particular trade: “metal tank (heavy gauge) manufacturing.” Wilson could only name one company in Utah in that business, and it happens to be located in his district. The state auditor revealed that the bill would cost Utah $500,000 in tax revenue, largely to benefit one company. It passed easily.

Salt Lake Tribune cartoonist Pat Bagley lampoons this way of doing business as the “buddy-ocracy,” and it happens all the time. Sometimes, as with Wilson’s bill, contributions aren’t even needed for the favor. And other times it appears as if legislators might be helping themselves out—for example, when they funded a major road project that happened to increase the value of a powerful member’s land holdings.

Not even the pandemic could stop the buddy-ocracy. In April, the legislature met in special session and set aside $6 million for the state to purchase and stockpile medications. Turns out a suburban pharmacist with connections to Senate President Stuart Adams had stockpiled hundreds of thousands of doses of hydroxychloroquine and zinc, the scientifically questionable treatment championed by President Trump.

GOP state Sen. Todd Weiler defended the bill on Twitter: “While the funds could be used for drugs like HCQ, they could be used for other potential treatments as well.” Soon it emerged that the state had already purchased $800,000 worth of the drug from this pharmacy, Meds in Motion, at vastly inflated prices. The state later rescinded the contract and sought its money back, but only after the deal was exposed and criticized by Democrats. Most of the time, however, the buddy-ocracy rolls on, unchallenged.

Next to cutting taxes, the second-most-sacred principle of Utah politics is the notion of local control—the right of towns and counties to decide what happens within their boundaries and on nearby federal lands (about two-thirds of Utah is under federal ownership, but in some counties in southern Utah it’s closer to 90 percent). Local control is an article of faith across much of the intermountain West (see: Bundy, Cliven), and Utah’s politicians are at its vanguard. The state maintains a Constitutional Defense Council that actively works to sue the federal government to try to get federal lands turned over to the state so the local people may drill, mine, and drive 4x4s to their hearts’ content.

The effort notched its greatest victory in late 2017, when the Utah congressional delegation, mining companies, and local officials persuaded President Trump to eviscerate Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments, which former President Obama had created in the southern part of the state. A key player in the lobbying effort was Phil Lyman, then a San Juan County commissioner, and a passionate proponent of local control.

In 2014, Lyman led a protest ATV ride into Recapture Canyon, which had been closed by the feds to preserve Indigenous archaeological sites. For that stunt Lyman spent 10 days in jail and was fined $96,955, but the episode made him a desert folk hero—and helped get him elected to the Utah House in 2018 despite his federal misdemeanor conviction. As his case proceeded, lawmakers urged the state to pay for his legal defense; when that was rejected, many pledged personal funds to his defense, including outgoing Gov. Gary Herbert. (He never paid, Lyman says, “but I told him I appreciated the gesture.”)

But when liberal cities want to assert local control, the legislature will have none of it. On the penultimate day of the 2018 session, the GOP supermajority passed a bill that effectively annexed 20 percent of Salt Lake City for a huge inland port for rail, truck, and air freight. The next year, it reduced the city’s authority over that land. The city has sued, but the project is moving forward in the meantime.

And when the coronavirus pandemic hit and the state went into lockdown, Lyman and other rural legislators were the first to complain that the reaction was overblown. Their pressure staved off a statewide shutdown order (instead, the governor asked for voluntary measures) because it overrode local control, but when Salt Lake County wanted to impose its own shutdown, the GOP majority attempted to curtail its ability to do so. Eight months later, Utah had one of the highest rates of spread in the nation.

“It’s a double standard—local control when it’s convenient,” says state Sen. Luz Escamilla, whose district includes the proposed inland port.

The medical marijuana campaign gave voters a new glimpse of their power—but it might never have happened if a Republican state senator named Mark Madsen had not almost died of a fentanyl overdose in 2007. He had been prescribed the painkiller for chronic back pain, but one summer evening, he says, a faulty patch leaked a sudden burst of the drug into his system. He was rushed to the hospital and resuscitated. After that he began treating his pain with marijuana—driving to Colorado to get it, as he later shockingly confessed to the media. Madsen is Mormon, but he was willing to go rogue in pursuit of his libertarian ideals. “I’m not spiritually accountable to church lobbyists,” he says.

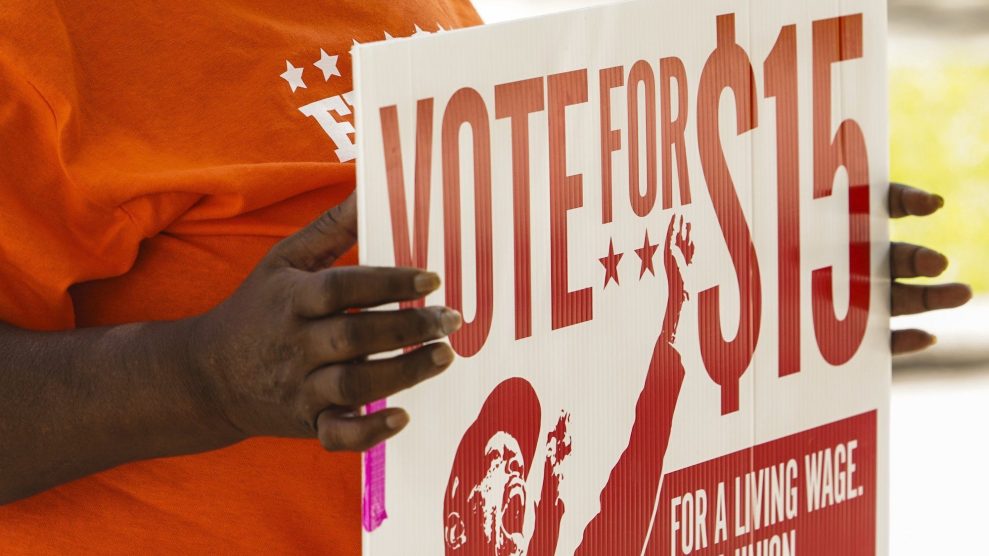

After trying twice to get a medical marijuana bill through the legislature, Madsen retired from the Senate, but advocacy groups picked up the baton. The only other option was to put the issue before Utah voters directly, a tremendously difficult undertaking. Mounting a ballot initiative requires organizers to collect the signatures of 8 percent of the active voters in the state, and those voters must come from at least 26 out of Utah’s 29 state Senate districts. Given that certain rural counties have just a few thousand inhabitants and are overwhelmingly Mormon, that is no easy task—one made still more complicated by a provision that allows signers to retract their signatures. The Utah Medical Association, the conservative local affiliate of the AMA, went door to door in some counties, trying to persuade people to do just that. When that failed, the LDS Church sent a letter to all church members opposing the measure, and a church lobbyist urged the faithful to “follow the prophet” and vote against it. The measure passed anyway, 53–47 percent.

Prop 2 upended the conventional wisdom that nothing happens in Utah without the blessing of both the LDS Church and the state GOP. “In the last 40 years, that’s pretty much their biggest defeat,” says former state Sen. Dabakis, who converted to Mormonism before later coming out as gay.

To Utahns old enough to remember when purchasing a mixed drink in a bar was next to impossible, it was mind-blowing. “Utah is changing in what will be a long-term transition to purple,” says Lyons, the Utah State University professor, “because the Mormon Church is losing its grip on the state.” He points to a 2016 survey that found that millennials and Gen Z-ers are far more likely to step away from the church than older generations, often over issues such as LGBTQ rights. And they’re almost as likely to vote Democratic as Republican. For their parents and grandparents, voting Republican was practically a commandment.

Almost as significantly, Proposition 2 brought a flood of new voters. Turnout spiked from 46 percent of registered voters in the previous midterm to 76 percent in 2018. While some voted only on medical marijuana, enough also favored Medicaid expansion and independent redistricting to pass those measures as well. Republicans dominated across the state, but ballot measures that the GOP opposed almost all passed. Whether these new voters upend the political balance of the state is yet to be seen.

The Biden campaign worked overtime to coax money from liberal Utahns, but at lower levels of the ballot, viable Democrats are still in short supply. The Democratic candidate for governor in 2020, for example, was an earnest law professor who seemed nice but had fewer than 10,000 Twitter followers.

This is why those who want to wrest control of the state from the GOP-LDS axis had their hopes set on Prop 4. “Our country is suffering from extreme polarization, and heavily gerrymandered districts helped cause that,” says Evan McMullin, executive director of Stand Up Republic, a group seeking to dial back partisanship generally. He’s indicated he might want to run for statewide office, and sees redistricting as key. “You get more unifying leadership when districts aren’t drawn to protect one party from competition from the other. I was encouraged that it passed in Utah.”

Has the legislature been contrite in the face of such popular opposition? Hardly. Its first reflex was to try to kill all three ballot initiatives, or at least gravely wound them. “I’ve heard legislators say it out loud that voters didn’t understand what they were voting for,” says state Rep. Jennifer Dailey-Provost, a Democrat whose district includes part of Salt Lake City. “And that’s just not the case. We have a lot of legislators who are not very deferential to the will of the public.”

Take Medicaid expansion. Legislators had voted down expansion in the past, and they weren’t happy that organizers had made an end run around them (as they have in five other reddish states, most recently Missouri). Eventually lawmakers reached a compromise that stopped short of full Medicaid expansion, instead covering fewer residents at a higher initial cost than plain expansion would have done. And as the left hand giveth, the right taketh away: Utah is one of 18 states suing to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which would render Medicaid expansion moot.

The legislative battle over redistricting dragged on the longest, perhaps because the stakes were highest. Proposition 4 had passed by less than 1 percent, and GOP legislators argued that it therefore wasn’t binding. Republicans also took offense at language prohibiting districts drawn for partisan or individual advantage, which redistricting advocates had insisted upon.

In the end, the anti-gerrymandering language was restored, but the final bill was greatly weakened. Reformers wanted to force the legislature to either approve the independent commission’s map or justify any changes to it; that requirement was dropped. Drawing the boundaries and approving them remains the job of the legislature, per the state constitution. The process will be much more transparent than in the past, but the independent redistricting commission is only advisory. Legislators will have the final say. Burbank, the political scientist, dismisses the final measure as “toothless.”

When redistricting takes place in 2021, its fairness—and the political future of the state—may depend on how much public criticism the GOP majority is willing to endure in order to hang onto power. Chavez-Houck believes the key to the state’s political future lies with its huge bloc of unaffiliated voters—at 561,000, more than double the number of registered Democrats in the state (versus 927,000 registered Republicans). “Unaffiliated voters are not affiliating with a party for a reason,” she says. “They don’t feel like they’re being heard. This moderate middle should be represented.”

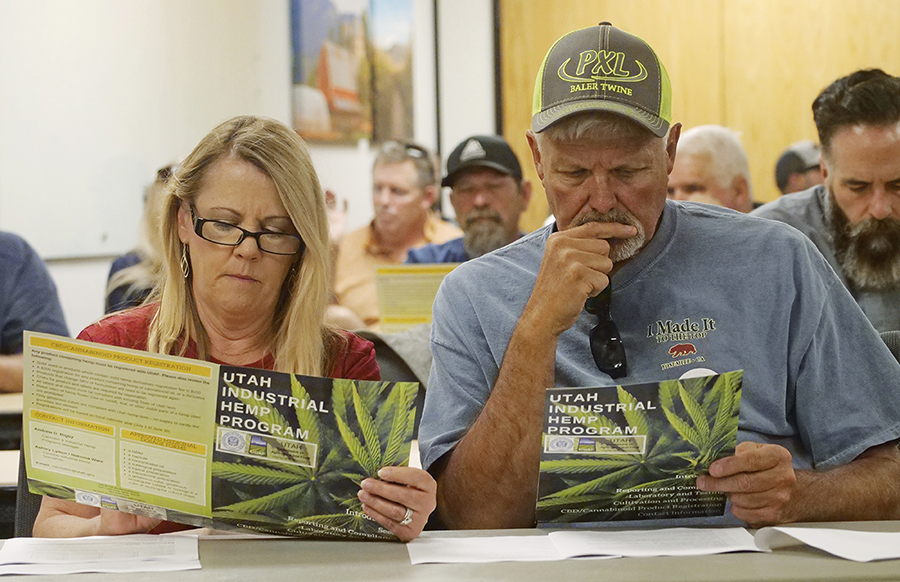

Farmers look on during a June 2019 hearing on cannabis at the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food in Salt Lake City.

Rick Bowmer/AP

Back at Dragonfly Wellness, which I visited in May, the patients are many, but products are few. “We have a harvest coming next week,” says Narith Panh, director of strategy for Dragonfly. “But we always sell out right away.”

As with the other ballot initiatives, the legislature had done its damnedest to undermine the wishes of voters. A medical dispensary application costs $5,000 in Arizona; in Utah, a license costs $100,000 but only permits the holder to sell a handful of rigidly specified products. Edibles may only take the form of a “gelatinous cube,” for example, and flower may only be vaporized, never lit with an open flame (i.e., no joints). Prospective patients must be diagnosed with approved conditions to obtain a marijuana card; “anxiety” doesn’t cut it. Mandatory testing of all marijuana products adds additional delays, and the state-mandated (and state-selected) inventory tracking and control software system has proved cumbersome and unreliable, says Greta Brandt, president of True North Organics, which operates two other dispensaries, in Ogden and Logan. (There are seven currently operating, and another seven on the way.)

These intensive regulations are the result of a hard-fought compromise hammered out between proponents of medical marijuana, legislative leaders, and the LDS Church. The final bill was so much weaker than the ballot proposition that one of the original sponsors, a patients’ organization called TRUCE, wound up suing the state to block parts of it.

“We had to satisfy [opponents] that this was not a hippie backdoor recreational program,” says Connor Boyack, president of the libertarian Libertas Institute, which backed Proposition 2 and played a central role in the negotiations. He feels the compromise was worth it. “Since then we’ve had unanimous votes [on bills related to medical marijuana], and broad support for medical cannabis.” (Interestingly, one key ally was Phil Lyman, a Mormon but also a libertarian.)

If legalized cannabis is a bellwether for political and social change, Panh himself is even more so. The 40-year-old Cambodian refugee was raised in the LDS Church, but he is no longer active in it. “I honestly thought Utah would have been one of the last ones to pass [medical cannabis] because of all the influence the church has,” he says. “Growing up here, you see how there is no separation of church and state here. But you are seeing a shift in opinions, a shift in beliefs, and you are seeing a lot more diversity in Utah.”

What is Utah’s future? Will it end up another Colorado or more like Idaho? Will the white male Republican majority hang on or will its power slowly erode? One sign came in last year’s gubernatorial primary, when GOP voters thoroughly rejected the Trumpiest candidate, former state House Speaker Greg Hughes. Another good sign: Romney remains as popular as the soon-to-be-ex-president, whom he regularly criticizes.

On Election Day, Trump handily won the state, though with far less of the vote (58 percent) than Romney in 2012 (73 percent). Republicans easily held on to their three safe House seats in Washington. In the one suburban swing district, a moderate incumbent Democrat named Ben McAdams narrowly lost to former NFL player Burgess Owens, who flirts with QAnon sympathizers and reportedly plagiarized big chunks of his book. The Democrats picked up one state legislative seat, but none in the state Senate, and one is not nearly enough to make a difference. Redistricting next year could move the needle a little, but not much. And in recent years, the legislature has made it more difficult to put a proposition on the ballot. “It might take another 10 years for the changes in the state to be reflected,” warns Galen, the Lincoln Project co-founder.

The most powerful force, then, may simply be time. “Initiatives are much better at predicting the future than individual races,” the conservative anti-tax activist Grover Norquist recently told the Washington Post. As Lyons says, “We’ve seen Colorado go from fairly red state to purple to blue, and the same forces are operative in Utah. We’ve got an influx of outdoor-oriented people, a thriving economy, and a growing Latino population. Salt Lake City is already blue. The same forces that are changing other states are evident in Utah. We’re just lagging substantially behind.”

If there is a purple future for Utah, it might look a lot like McMullin, a former intelligence officer and former GOP Hill staffer with the earnest persistence of an LDS missionary. He is pro-life and pro–good government, both of which are valued in Utah. More importantly, he is Not A Democrat; voting Democratic remains taboo in much of the state. He toyed with a statewide run in 2018, after his independent presidential candidacy, but backed off. Now, he leaves the possibility open. “I do plan to pursue public office again,” he says. In a fairer, more balanced, post-Trumpian Utah, he may have a chance.