Sen. Kelly Loeffler stands in front of an image of her and Sen. David Perdue.Jessica McGowan/Getty Images

Sen. David Perdue has hit a tough string of headlines recently that are complicating his effort to win reelection as a Republican in Georgia. The coverage shares a theme: Perdue used his position in the Senate to enrich himself and his wealthy donors. The stories follow the revelation from this spring that Perdue, a multi-millionaire, traded stocks following a private January briefing on the coronavirus at the same time he publicly downplayed the pandemic’s threat.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because his colleague Sen. Kelly Loeffler (R-Ga.) did the same thing, sparking a Senate ethics investigation. Together, Perdue and Loeffler make a unique pair: two uber-rich senators whose wealth helped bring them power and put them in a position where they could make more money. The last thing Perdue and Loeffler want is for their actions to become the theme of Georgia’s crucial runoff elections, which together will determine if the Senate remains under Republican control.

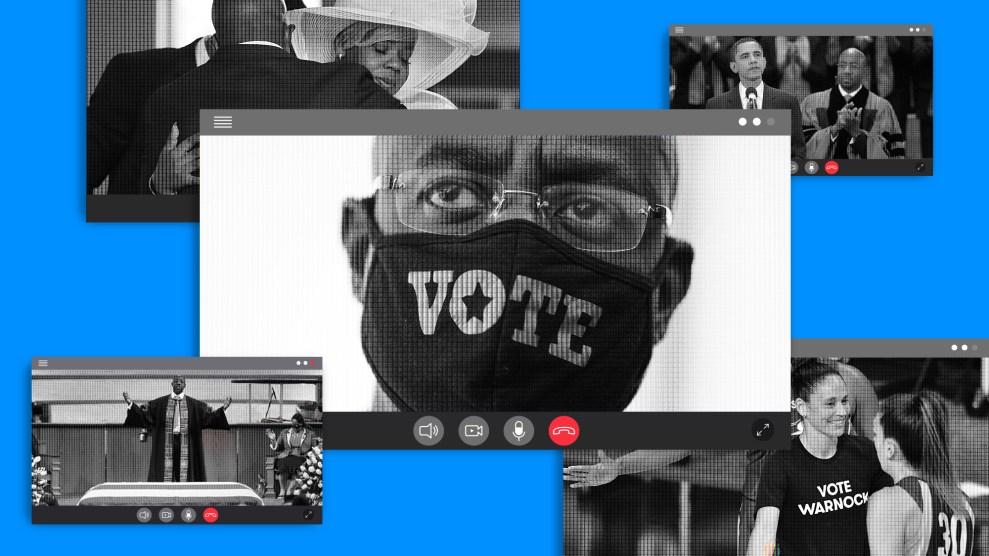

After both failing to notch over fifty percent of the vote on November 3, the senators are headed to January 5 runoffs against Democratic challengers, with Perdue facing Jon Ossoff and Loeffler vying against Raphael Warnock. Traditionally, runoffs in red southern states are a mechanism that have helped ensure Republican victories. But the old math may be different this year: Georgia went for a Democratic presidential candidate for the first time since 1992, in part because reliable voters in the suburbs bucked the GOP. Democrats have a chance to win both runoffs if those high-turnout voters show up in January convinced the two sitting Republicans are crooked.

Instead, the Republicans have sought to nationalize the race, and fan fears among their base of the consequences of Democrats taking control of the Senate. “We have to remind people of what the Democrats will do,” Perdue told supporters on a recent call that was leaked to the Washington Post. “It has nothing to do with Kelly or me.”

But Democrats see a clear opportunity in making the race all about Perdue and Loeffler and their stock trades. Perdue, who was elected in 2014, and Loeffler, appointed in January, are both very rich. In August, Forbes estimated Loeffler and her husband, Jeff Sprecher—the CEO of Intercontinental Exchange, which owns the New York Stock Exchange—are worth $800 million, making her the richest member of Congress. Perdue, the former CEO of Dollar General, is worth between $14.9 million and $42.6 million, according to his last financial disclosure, which reports value ranges for individual holdings.

While both Loeffler and Perdue have denied wrongdoing related to their investments and said they relied on portfolio managers to make day-to-day decisions, watchdog groups warn that lawmakers trading individual stocks, while legal and allowed under Senate rules, inevitably risks conflicts of interest while creating a perception they are personally benefiting from official actions. As a result, most members of the Senate refrain from trading in individual stocks.

“This has every appearance of insider trading and even if not, it creates the appearance of a conflict of interest,” says Craig Holman, an exert in ethics issues for the watchdog group Public Citizen, of the Georgia lawmakers’ trades. “They just don’t care.”

On January 24, just three weeks into her Senate career, Loeffler attended a private Senate briefing by Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Dr. Robert Redfield, the head of the Centers for Disease Control, about the coronavirus threat. Afterward, Loeffler continued to publicly downplay the risk from the virus and its economic impact. But in the three weeks following the meeting, Loeffler and Sprecher made more than 20 stock sales amounting to between $1.25 million and $3.1 million. Loeffler also bought stock in two companies that produce teleworking software.

Once markets began plummeting in late February, the couple sold $18.7 million in shares of Intercontinental Exchange stock in three separate deals. They also sold shares in retail stores like Lululemon and T.J. Maxx, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Loeffler has denied profiting off confidential information, and notes that her trading was investigated by the Senate Ethics Committee. The panel told Loeffler in a June letter it found “no evidence” she broke the law or Senate rules. In an April Wall Street Journal op-ed where she promised “to end the distraction,” the senator reiterated that her investments are managed by third party advisers, and claimed that the January 24 briefing included “no material or nonpublic information.”

While Loeffler wrote that her household would “divest from individual stocks,” her subsequent financial disclosure form showed that she kept $5 million to $25 million worth of Intercontinental Exchange stock, while her husband held on to at least $10 million worth of the company’s stock and options. As a member of the Senate Agricultural Committee, Loeffler helps oversee the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. That agency regulates Sprecher’s company, giving her influence over the performance of a firm in which she remains heavily invested. Upon joining the committee, Loeffler said she would “recuse myself if needed on a case by case basis.” In May, she announced she was stepping down from a subcommittee with direct oversight of the CFTC in response to criticism, but she retained her seat on the full committee.

Perdue attended the same January 24 briefing, and was active in the stock market the very same day, buying, as the Atlanta Journal-Constitution first reported, as much as $65,000 worth of stock in DuPont, the chemical and materials giant that makes protective equipment including gloves, gowns, and masks. According to a financial disclosure report, between the day of the briefing and early March he made 10 different purchases of the firm’s stock, amounting to an investment of up to $185,000. Purdue made hundreds of other individual stock trades in the first months of 2020, including investing up to $50,000 in Netflix, while offloading stock in Caesar Entertainment, a casino company, and nearly $400,000 in shares of Kroger, the grocery store chain.

While the coronavirus briefings presented senators clear opportunities to make well timed trades, lawmakers are regularly involved in or have foresight of policy decisions that will affect the financial prospects of companies or entire industries. In September, the Daily Beast reported that Perdue bought stock in First Data, a card payment processing company with business in prepaid cards, after he pushed to weaken prepaid debit card regulations. Perdue, or a financial adviser working for him, repeatedly bought and sold First Data stock, with some transactions coinciding with federal policy announcements affecting the firm.

In January 2019, Perdue, a vocal advocate of increased Navy spending, became the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower. In the six weeks before taking over, Perdue bought $40,000 to $290,000 of shares in a Navy contractor, BWX Technologies, the Daily Beast first reported last week. In the month after Perdue’s appointment, the stock’s value increased by more than 25 percent. Perdue quickly pocketed the profit, selling the stock between February and July 2019.

Perdue has responded to questions about these transactions by saying he relies on outside advisers who make trades “without his prior input or approval,” according to a spokeswoman. But Perdue, unlike some lawmakers, has not placed his assets in a blind trust, a widely accepted practice that would ensure he is not personally involved in buying and selling stocks, including those he could potentially influence with official acts.

Perdue hasn’t just been out to help himself. In 2017, Perdue unsuccessfully sought a tax break for the uber-wealthy owners of sports teams, a tax regulation that would have benefited several of his wealthy donors. Among them was Loeffler, who co-owns Atlanta’s WNBA team.

Self-dealing is never a good look when running for reelection, and Perdue and Loeffler clearly don’t want the runoffs to focus on this history. In October, Perdue bailed on his final general election debate after Ossoff called him a crook in their second debate and the moment went viral. Loeffler, for her part, is worried enough about the stock sales that she ran an ad claiming she’d been “cleared” and that she always “puts Georgia first.”

President-elect Joe Biden won Georgia in part by drawing support from Atlanta suburbs that not long ago were a Republican stronghold. These suburban Republicans “are the reason that we never had a chance in runoffs in the past, because they always voted,” says Chris Huttman, a Democratic strategist in Georgia. “They weren’t necessarily conservative, but they were very Republican.”

But in 2016, turned off by Trump, some of these Republicans began voting for Democrats, and continued doing so in the 2018 midterms and this November, as the counties that make up and surround Atlanta gave Biden his margin of victory. But returns in suburban Atlanta counties show that Perdue outperformed Donald Trump, and Ossoff underperformed Biden, meaning that a significant number of Republicans outside Atlanta split their tickets and voted for Biden and Perdue. Perdue and Loeffler must hold onto these voters in the runoff. “I’m talking about people that may have voted for Biden,” Perdue said on the leaked call with Republicans. “We think some of those people, particularly in the suburbs, may come back to us. And I’m hopeful of that.”

Democrats, on the other hand, need to turn Biden voters who supported Republican Senate candidates in November into Ossoff and Warnock voters in January. Perdue and Loeffler may be doing some of that work themselves. In an effort to keep Trump’s base engaged, Loeffler and Perdue have associated themselves with right-wing push to overturn Georgia’s November election results, calling on the Republican secretary of state to resign. The antics are part of a tricky dance: remaining as close as they can to Trump and his supporters while also trying to hold onto anti-Trump suburbanites.

For their parts, Ossoff and Warnock ran their general election campaigns on bread-and-butter issues, particularly health care. As the pandemic raged, they hammered their support for protecting coverage for people with pre-existing conditions, which Republicans repeatedly voted against while attempting to repeal the Affordable Care Act. But that message didn’t get them across the finish line in November.

“Republicans just lie about the pre-existing condition stuff,” says Huttman. “Their answer to that is like, ‘No, I’m the pre-existing conditions person.’” That’s left voters with a jumbled message. But for the runoff, an anti-corruption and anti-crook message promises to be more straightforward. “I do think there’s some opportunity there just to divorce yourself from the party aspect of it: ‘These are just bad people who you shouldn’t be trusting to make tough decisions.’ I definitely think that’s the way to go,” Huttman says.

The message could also dampen participation among the occasional voters who turned out for Trump, but whom Perdue and Loeffler might struggle to convince to vote in the runoff. “If you think about these Trump surge voters, the only person they’ve ever turned out to vote for is Trump,” he says, noting that they can be skeptical of other politicians. “Why not tell those people that there’s really nothing for you here, either? That really scrambles the traditional runoff turnout patterns that people have relied on,” Huttman says. The deficit could help put the swing GOP voters in the Atlanta suburbs, even though he says they might only make up about 3 percent of the voters taking part in the runoff, in the driver seat.

That’s not the race that Republicans want to run. On the leaked call, Perdue said the contest was about base turnout and that he wanted to keep the focus on Democrats. “This is really not about messaging. It’s not about persuasion in my race. It’s more about getting the vote out,” Perdue said, a statement that suggests an assumption that he’ll hold suburban Atlanta voters who checked his name over Ossoff’s in November.

A member of Ossoff’s campaign who spoke on the condition they not be named said corruption would be a key talking point in the runoff. “Georgians are struggling,” they said. “Georgians are struggling to make rent, small businesses struggling to stay open. People can’t spend Thanksgiving with their families. And David Perdue is looking to make a quick buck. And it seems to be a pattern in his career as a senator.”

Other Democrats have joined in, helping paint an unflattering picture of corruption and self-dealing around Georgia’s two Republican senators. As former President Barack Obama said during a Georgia campaign stop this month, Loeffler and Perdue “were publicly telling you that the virus would be no big deal, but behind closed doors they were making a bunch of moves in the stock market to try to make sure their portfolios were protected instead of making sure you were protected.”

“Man, that’s shady,” he concluded. “That ain’t right.”