Jamaal Bowman attends a news conference on Capitol Hill on September 23, 2020. Tom Williams/Congressional Quarterly via ZUMA Press

Cori Bush wanted to make something clear when I spoke with her the day after the election. “I don’t hate police,” she said gently. The newly elected House member had unseated a 20-year incumbent in Missouri’s safely Democratic 1st District based on her record of activism in Ferguson, where the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown turned Black Lives Matter into a national movement. During her primary, Bush told me that the House’s police reform bill, passed a month after George Floyd’s death, was “too soft” and criticized its lack of “real ‘defund’ language.”

“Defund the police” is shorthand activists like Bush have long used to describe their desire to slash police budgets and reinvest those funds into social services. But the parlance of her movement, she told me, had been distorted and weaponized by her GOP opponent during the general election, who painted her as “this anti-police, hateful person,” she told me in our call after her win. “I loathe what [police] allow—the fact that they’ve had problems in their departments, in their unions, that they have not addressed,” Bush clarified. “And the result is dead bodies who look like me.”

Bush didn’t aim her explanation at anyone in particular, but it eerily anticipated the criticism that her soon-to-be-colleague Rep. Abigail Spanberger lobbed on a call with fellow Democratic House members the following day. “If we don’t mean ‘defund the police,’ we shouldn’t say that,” the moderate first-term House Democrat, who nearly lost her race in central Virginia, seethed. She also said, “We need not ever use the word ‘socialist’ or ‘socialism’ ever again.”

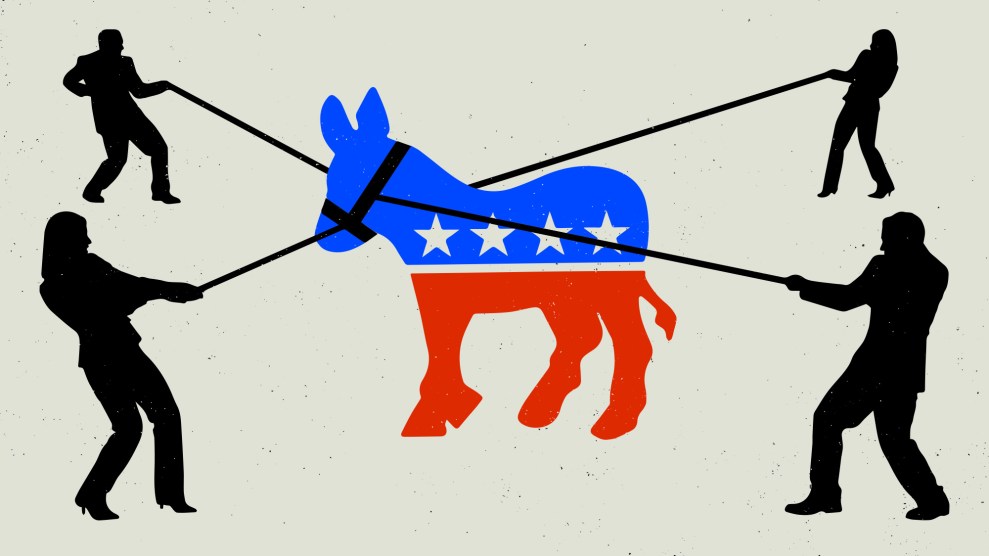

Bush’s tenure in the House begins just as Democrats’ intraparty warfare reaches a new crescendo. The brief armistice that pushed President-elect Joe Biden over the finish line ended once the down-ballot results revealed Republicans had taken back at least half a dozen House seats. Some, like Spanberger, laid the blame at the feet of “squad” members like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) for tagging the whole party with their left-wing views. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), a top contender to one day succeed Nancy Pelosi as House Speaker, asked on a separate call with members of House leadership last week: “Do we want to win, do we want to govern, or do we want to be internet celebrities?”

But as this proxy war over the party’s future plays out in the House, the chamber’s progressives find themselves in a rare posture of strength. Justice Democrats, the left-wing group that backed Ocasio-Cortez in her 2018 primary victory, successfully unseated three moderate Democratic House members with progressive candidates. In open seats, a number of liberal candidates who supported Medicare for All and the Green New Deal replaced retiring lawmakers who did not. Among those joining Bush are a pair of New Yorkers, Jamaal Bowman, a former Bronx principal who unseated Rep. Eliot Engel, and Mondaire Jones, one of House’s first-ever openly gay Black members (who ran as a progressive but didn’t have Justice Democrats’ backing). A number of them, like Bush, owe their victories to the racial justice uprisings in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, for which “defund the police” is a rallying cry.

Ocasio-Cortez and her three fellow squad members showed up with big ideas and soapboxes to match two years ago, but no power in an institution where strength is measured in numbers. “That’s like, five people,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) sniped last summer in an interview with 60 minutes, a summation that was dismissive if not inaccurate. “And I said, all right, let’s go get more,” Ocasio-Cortez told the Daily Beast in July. “So, we’re getting more votes, we’re getting more people.”

Now, the squad’s ranks will nearly double when the next Congress starts, and the loss of moderate Democrats in swing districts have given the left a larger—if still minority—share of the House Democratic membership. As the newest class of progressives enter the hornet’s nest, they’re grappling with how to best wield their positions and platforms.

To Ocasio-Cortez and her leftist allies, the censure from moderates amounts to an effort to silence the progressive wing instead of grappling with the racial resentment that fueled GOP attacks in the first place. “That’s their argument with defunding police, right?” Ocasio-Cortez told the New York Times last week. “To not agitate racial resentment. I don’t think that is sustainable.” Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) questioned why unity always seems to come at the expense of the party’s left flank—especially when many of those leftist lawmakers represent marginalized populations. “If we truly want to unify our country, we have to really respect every single voice,” Tlaib said. “We say that so willingly when we talk about Trump supporters, but we don’t say that willingly for my Black and brown neighbors and from LGBTQ neighbors or marginalized people.”

Incoming House progressives I spoke with echoed Tlaib’s concerns. “We have people who have been, historically, not part of the conversation becoming a central voice in the conversation,” Bowman, who is Black, tells me. “Those who have lost faith in our political system are gaining faith because of candidates like me. They see people who look like them, who sound like them, to speak about the issues they care about.” Jones tells me that “to be silent is to abandon the people who sent me to Washington to do a job—and that is to speak truth to power and to fight for the big structural changes that are going to meet the moment.”

It’s why Jones doesn’t plan on giving up his ambitions to expand the Supreme Court—even as his moderate colleagues perhaps wish he would and he faces a GOP-held Senate undoubtedly hostile to the idea. Bowman joined Jones for a virtual organizing call on packing the courts last week. “I’m now faced with a Supreme Court majority that is hostile to my civil rights, and of course, to the voting rights of Black and brown Americans, and to democracy itself,” Jones says. But he’s also signaling pragmatism. “Court expansion wasn’t going to happen overnight,” he acknowledges, and says he’s eager to be a “bridge-builder” who can unite his colleagues around “areas of common ground” with his more moderate colleagues.

Bush has adopted a similar stance. “By us being this force that continues to grow, we can apply more pressure in the areas where we feel like we need to see change,” she tells me, explaining that Medicare for All in 2016 and the Green New Deal in 2018 are examples of how a persistent progressive bloc can make ideas “more mainstream.” But, Bush adds, “I think that it’s going to be something that we’ll have to be very careful about because we don’t want to lose our voices.”

So far, Bush has kept to her activist roots: She showed up to House orientation wearing a face mask emblazoned with the name of Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old Black woman shot to death by police in her home in Louisville, Kentucky, this past spring.* A few of her new Republican colleagues have called Bush Breonna, assuming it’s her name. “It hurts,” she tweeted. “But I’m glad they’ll come to know her name & story because of my presence here. Breonna must be central to our work in Congress.”

Marie Newman, who defeated anti-abortion Rep. Dan Lipinski (D-Ill.), thinks the ever-worsening pandemic is still a good time to make the case for the top items on progressives’ wishlists. “I think there’s a huge opportunity for Medicare for All,” she told me, noting that it’s up to lawmakers like her to help make the case for it as a “practical path forward.” She hopes that she and her colleagues train their focus on the most popular ideas with broad support, like universal childcare and a green stimulus package. Bowman added that coronavirus revealed how racial justice and economic inequality, both at the center of his campaign, are interconnected. “We’re at an urgent moment that we have to govern aggressively and urgently to get out of,” Bowman told me.

What they’re embarking on, in other words, is a balancing act of scorched-earth activism and party unity. Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), a progressive lawmaker just elected to his third term, told me he worried the two runoff races in Georgia that will determine control of the Senate might necessitate a need for factions to tap the breaks. “There are times to push and bring things to a head, and there are times to regroup and ready the ground,” Raskin says, “We still don’t know what time it is.”

But, Raskin adds, that shouldn’t involve bending over backward to meet Republican demands. “Our rhetoric should not be, ‘Oh, now that they’ve trashed our entire democracy and plunged us into debt, starvation, drought, international isolation and war, let’s sit in a circle and sing kumbaya together,” Raskin says. “The last thing anybody wants is a series of establishment lectures about civility and bipartisanship.”

*An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the city where Breonna Taylor was murdered as Lexington, Kentucky, not Louisville.