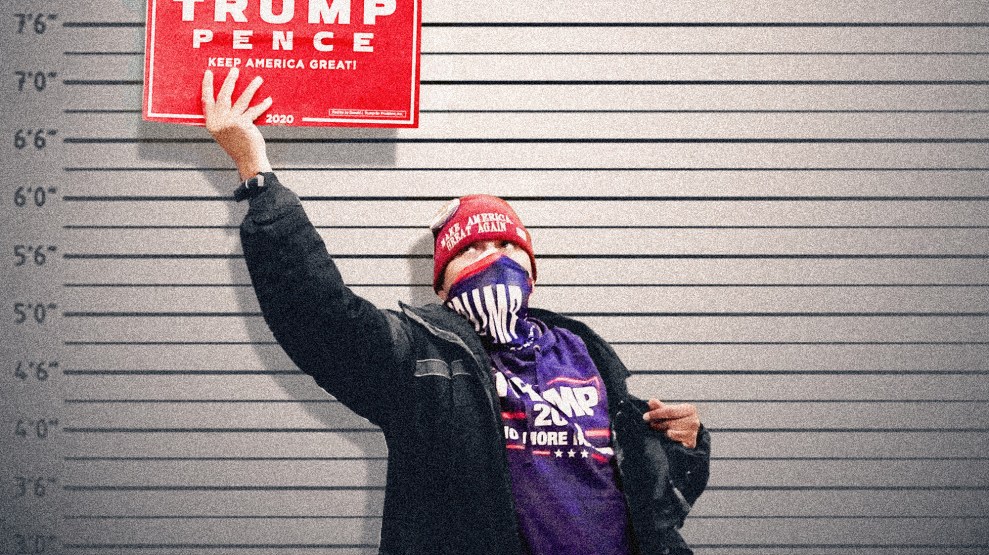

Mother Jones illustration; Chris Kleponis/Sipa/AP

On Wednesday, as a nation looked on in horror, a mob incited by President Donald Trump stormed the United States Capitol. Videos showed the insurgents destroying property, terrorizing workers, assaulting police officers, forcing members of Congress to evacuate, and disrupting certification of the presidential election won by Joe Biden. The list of crimes they may have committed is extensive.

The criminal charges prosecutors could pursue against members of the mob and/or the political leaders who incited them, according to interviews with six former prosecutors and public defenders, include the following: destruction of government property, rioting or inciting to riot, conspiracy, burglary, assaulting a police officer, carrying a dangerous weapon, unlawful entry, prohibited entry into restricted grounds, seditious conspiracy, and insurrection.

The people with potential criminal liability range from those who rioted outside the Capitol to some of the nation’s leaders, including the president. Somewhere in between are members of the mob that stormed the Capitol, especially their ringleaders. The maximum sentences for crimes such as seditious conspiracy can run as high as 20 years, although most of the people I interviewed considered multi-decade sentences unlikely.

According to a statement Thursday, the Capitol Police had arrested only 14 people in connection with the attack, during which more than 50 Capitol and local officers were injured and one woman was shot and killed inside the building by a Capitol Police officer. On Friday, law enforcement officials in Arkansas arrested Richard Barnett, a resident of the state who was photographed with feet on a desk in Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office. West Virginia Republican Del. Derrick Evans was also charged on Friday for his role in the rioting, NBC news reported.

Bennett Gershman, a law professor law at Pace University who served as a prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office and a special prosecutor in the New York State Anti-Corruption Office, started off by listing some of the obvious offenses, such as unlawful assembly, that were likely committed. But “this goes to a scale that is so far beyond just simple protest or demonstration,” he said. “This is mob violence against persons and property.”

“These people were engaging in insurrection against our democracy—against the Constitution,” he added. “So I would look carefully at terroristic crimes and physical violence in pursuit of terroristic objectives.” Gershman said he’d need to go back and study the language of the treason statute before ruling out treason as a charge.

Thiru Vignarajah, who has served both as a federal prosecutor and as deputy attorney general of Maryland, also raised the possibility of domestic terrorism charges: “You’re talking about a mob that stormed the Capitol…for the purpose of interfering and ultimately seeking to thwart the peaceful transfer of power. And that motive is a predicate for a potential terrorism prosecution.”

Prosecutors could also press charges ranging from destruction of property to insurrection and rebellion, Vignarajah added. The context of Wednesday’s events is important: “This is no ordinary destruction of federal property; this is no ordinary civil disturbance,” he said. “It would not be surprising to see more attention, more resources, more energy behind the investigations and potential prosecution by the next Justice Department.”

Gershman told me he wouldn’t be surprised if the mob’s ringleaders serve three to five years behind bars. “This is not something that judges are going to be soft on,” he explained. “You saw the videos of breaking into the Capitol the way they did—debris all over the place—just destroying the place of our democracy.”

Phil Andonian, a former DC public defender now in private practice at Caleb Andonian, thinks judges will likely sentence the ringleaders to a year or more. “It’s hard to imagine a judge finding it in him or herself to sentence to something less than that and have it be on the top fold of the [Washington] Post—basically slapping the wrist of somebody who did what British soldiers did last 200 some odd years ago,” he said.

In the wake of Wednesday’s events, Andonian reviewed the federal statute describing seditious conspiracy. The law prohibits any group of two or more people from, among other things, conspiring to overthrow the government, oppose its authority by force, and delay execution of any law: “I can’t make a good argument, even as an inveterate defense attorney, as to why this is not an absolutely black-letter-law, open-and-shut case of seditious conspiracy—starting with Trump all the way down.”

“We had a literal invasion of the seat of government on the day they’re certifying a duly held presidential election,” he continued. “And they took over and required shelter in place and evacuations. I mean, what else is that?”

Andonian helped defend the more than 200 people arrested in 2017 for alleged Inauguration Day rioting in what became known as the J20 case. The prosecutors in that case, pursuing felony charges with maximum sentences of about 70 years, argued that they didn’t have to show that any of the defendants had actually damaged private property—merely being in the vicinity of people who did things like break windows was enough to be guilty of felony offenses. This was an “utterly novel and totally insane theory” that Andonian had never seen before. (It ultimately failed in court, and most of the charges were dismissed.)

If prosecutors adopted a similarly broad approach in the Capitol Mob case, they’d be on more solid legal ground, according to Andonian: “There just seems to be no way to argue that if you were there yesterday, you were there for any reason other than what Trump and his confederates were explicitly calling for.”

But he expressed skepticism that prosecutors would take such a hard line. “I’ll state the obvious: It’s a group of white people from wherever,” Andonian said. “It might not look like the J20 indictment. If it were BLM, I assume it would be the J20 indictment and then some.” Indeed, had the Capitol Mob consisted primarily of black men, “there would be bodies piled up on the street right now.”

The job of the prosecutors may be easier, too, given how thoroughly the invaders’ activities were documented by the news media—and participants themselves. Joyce Vance, a law professor at the University of Alabama who served as the the US Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama under President Barack Obama, offered the following anecdote. “One of my favorite cases that we ever prosecuted were some folks who were trafficking in contraband who had the great good sense to take video and pictures of themselves and put it all onto their social media,” she said. “The jury came back awfully quickly.”

She stressed the importance, however, of not prejudging crimes, and of using prosecutors’ limited resources wisely. “For my money, I believe the prosecutors should focus on serious crimes and not just pick low-hanging fruit,” she said. “And so that would lead me to consider first the conduct of people like the president of the United States, like Alabama Congressman Mo Brooks.” (At a rally preceding the attack, Brooks told the crowd, “Today is the day American patriots start taking down names and kicking ass.”)

“These are serious charges,” Vance cautioned. “We do not need any kind of a rush to mob justice. But we do need accountability. I think that we saw very likely sedition and solicitation to violence today committed by some of our country’s leaders.”

This story has been updated to include arrests on Friday.