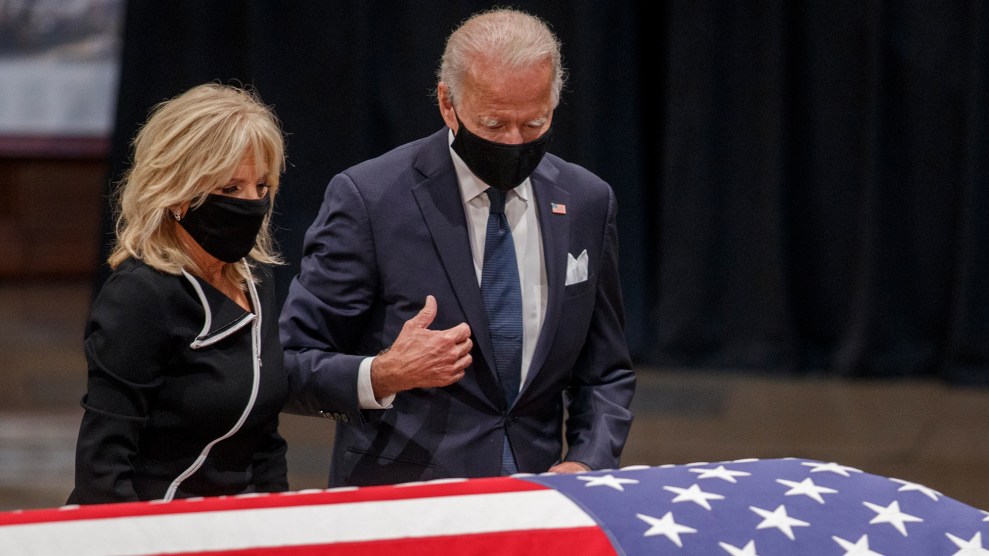

The Bidens pay their respects to the late John Lewis in the Capitol Rotunda on July 27, 2020.J. Scott Applewhite/Pool/Getty

On the 56th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, just days after House Democrats passed a sweeping voting rights bill in response to attacks on the voting process by former President Donald Trump, President Joe Biden issued an executive order directing federal agencies to take efforts to make voting easier.

Though limited, the order tells federal officials to study and expand access to voter registration and election information and modernize the Vote.gov website. It also directs federal agency heads to give their employees time off to vote or volunteer as poll workers. But it won’t do much to counter prolific Republican efforts to restrict state-level voter access under the false premise of election fraud.

“Every eligible voter should be able to vote and have it counted,” Biden said in recorded remarks to the Martin and Coretta King Unity Breakfast before he signed the order. “If you have the best ideas, you have nothing to hide. Let the people vote.”

But the real battle over upholding the spirit of the Voting Rights Act—and really, the foundation of American democracy—rests in the halls of Congress and statehouses throughout the country. As my colleague Ari Berman has reported, more than 250 bills to restrict voting access were introduced so far this year in 43 states—notably Georgia, where Republican lawmakers are pushing a repeal of no-excuse absentee voting, requiring the small slice of voters who cast ballots by mail to get a witness signature on their ballot and attach a copy of photo identification. GOP lawmakers have also pushed for legislation to end Sunday voting, which would suppress Black voter turnout and has been described as “Jim Crow with a suit and tie.”

House Democrats passed a bill last week aimed at derailing just such endeavors. Berman writes:

On Wednesday, the House of Representatives passed HR 1, dubbed the For the People Act, the most significant democracy reform bill since the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The bill would go a long way toward thwarting the new GOP voter-suppression efforts by enacting a wide range of pro-voter measures for federal elections. This includes nationwide automatic and Election Day registration; two weeks of early voting in every state; the expansion of mail-in voting; the restoration of voting rights to people convicted of a felony who have served their time; restrictions on discriminatory voter-ID laws and voter purges; and the creation of independent redistricting commissions for House districts to prevent extreme gerrymandering. The bill also cracks down on dark money by implementing public financing for congressional campaigns, and it establishes new ethics rules for federal officeholders.

But the bill is doomed in the Senate, given that any contested bill requires 60 votes to advance. So the voting rights battle is shaping up to be a fight over the filibuster. As Berman further explains:

“I’ve always thought HR 1 would be the most likely place for the filibuster to come to a head,” says [author Adam] Jentleson. “It’s a question of existential survival for Democrats and democracy writ large. And Republicans will go to the mat to keep it from passing. You’ll never see 10 Republicans support it.”

[Sen. Amy] Klobuchar plans to hold hearings on S 1, the Senate version of the voting rights bill, in the Rules Committee this month and then advance the bill to the Senate floor, setting up a potential showdown over the filibuster. Democrats have a few options at their disposal. They could end the filibuster outright with a simple majority vote (with Vice President Kamala Harris casting a tie-breaking vote), or they could abolish the filibuster only for election-related bills that are critical for democracy, an idea floated by Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) They could also force Republicans to speak continuously on the Senate floor to sustain a filibuster—as was done in the old days—which would make it tougher for Republicans to wield the filibuster. Another option: lower the threshold for passing filibustered bills from 60 votes to 55 votes.

The filibuster was once the primary tool used to block legislation that would protect voting rights, such as a proposed law banning the poll tax. “In the 87 years between the end of Reconstruction and 1964, the only bills that were stopped by filibusters were civil rights bills,” Jentleson writes in his book. Abolishing the filibuster to pass HR 1 would be “poetic justice,” he says. “You would be ending the filibuster on an issue of civil rights.”

Speaking with the Guardian on Sunday, House Majority Whip James Clyburn insisted there is “no way” the Democrats will let the filibuster get in the way of voting rights. But abolishing the filibuster entirely seems impossible, given resistance from conservative Democrats such as Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema.

There are other options, though. On Sunday, Manchin took to the talk show circuit to emphasize that he would not vote to kill the filibuster, but said he was open to changes that would make it harder to use. He told host Chuck Todd of NBC’s Meet the Press that he would not support passing the voting rights bill with a simple majority unless there had been what he deemed a sufficient effort to seek compromise with Republicans.

WATCH: Sen. Manchin tells @chucktodd, "I'm not going to change my mind on the filibuster." #MTP@Sen_JoeManchin: "I’ll change my mind if we need to go to a reconciliation … But I'm not going to go there until my Republican friends have the ability to have their say also." pic.twitter.com/rzDnE18rTA

— Meet the Press (@MeetThePress) March 7, 2021

It may require a gutting of the filibuster to fulfill the ambition of the late Rep. John Lewis, who was badly beaten as he and others marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge more than a half-century ago: to restore voting rights. It was the events of Bloody Sunday that galvanized support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Lewis died last July, but his dream remains alive for now.