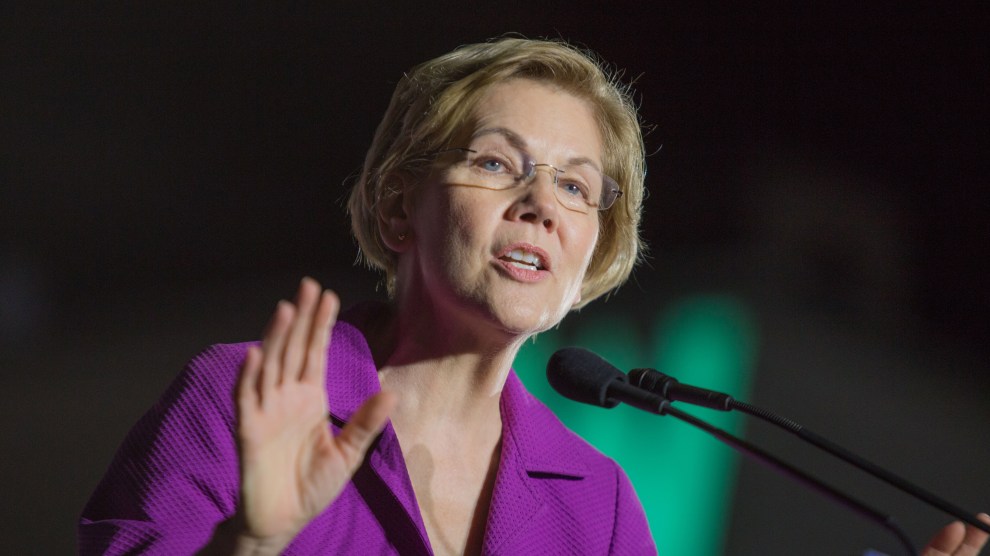

Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Zuma

Elizabeth Warren wanted Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Mary Jo White out, and she wanted her out immediately.

Over the course of 12 pages and 57 footnotes in an October 2016 letter to President Barack Obama, Warren excoriated White for—among other transgressions—using SEC resources to push an anti-disclosure initiative “cooked up by big business lobbyists.” That was the last straw in a yearslong clash between the Massachusetts senator, a ferocious critic of Wall Street, and White, who had defended banks as a private attorney. Never mind that Obama had just three months left in his term and, a week after the November election, White would announce her own departure. White’s “brazen conduct,” Warren told Obama, had undermined Congress, his administration, the SEC, and the investors it serves. “Enough is enough,” Warren wrote.

White was just one in a long line of Obama-appointed financial regulators who incurred Warren’s wrath. She’d been incensed by the revolving door between the banks and federal government ever since she was a law professor studying personal bankruptcy at Harvard. That same revolving door had kept Warren from running the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the agency she’d created, because bank-sympathetic Democrats and Republicans alike worried what such a strident critic would do as its head. Instead, she settled for helping to launch the agency before returning home to Massachusetts.

But over the past four years, Warren’s standing has shifted, and her views have earned a hard-fought place of respect within her party. Warren likely won’t clash as much with the next SEC chair, pending Senate confirmation: Biden nominated Gary Gensler, a former investment banker and Commodity Futures Trading Commission chair who has become an unlikely but loyal ideological ally for Warren. And the people who helped to advance Warren’s argument have earned their places, too: Bharat Ramamurti, her former top economic policy hand who helped craft those letters against White’s SEC, is now a deputy director of the National Economic Council, the White House’s nerve center for economic policymaking.

Ramamurti is far from the lone Warren acolyte who has landed a prime job now that Biden is president. The administration has also tapped a number of her first hires to the CFPB, such as Rohit Chopra, a likeminded progressive who has been named to lead the agency. Some of her former Senate aides have been appointed to key roles across the federal agencies, such as Julie Siegel, who helped develop Warren’s aggressive private equity proposal and now holds a top post at Treasury. Others have decamped to jobs at Health and Human Services, the National Security Council, and the Education Department.

Over her eight years in the Senate, Warren has mentored a fleet of former staffers who now hold roles in the Biden administration, a peak expression of her mantra of “personnel is policy.” And despite the fact that she didn’t win the presidency, she is having a tremendous influence on how the Biden administration will operate. “I can do so much as a senator,” she tells me, “but the people who’ve come from my office will be able to do so much more, far more.”

Gene Sperling, a former NEC chair under Obama and one of the economists who advised Warren on her campaign’s central wealth tax proposal, recalls Warren describing the Senate’s levers of power as a tier system. The first level is using the platform to change the political debate; the second is pushing legislation; and the third is “fighting in the trenches at every level,” work that requires getting deep in the legislative and regulatory weeds. “She knows that everyone pushes hard on the second level,” Sperling said, “but that she could have a uniquely powerful impact by fully throwing herself into the first and third levels as well.”

As the leader of a congressional panel overseeing Congress’ $700 billion bank bailout in 2008, the Harvard law professor turned a toothless committee into a massive platform for her plainspoken explanations of how the government had abetted a financial system rigged in favor of the few. When she spent a year setting up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2010, Warren emphasized “talent and culture,” a former Obama official told Politico. When she entered the Senate instead of becoming the CFPB’s first chair, Warren decided to keep focusing on building up a network of allies by hiring the right people to be her staff. “I thought about, ‘What are all the resources available to a senator to make change?’” Warren says. “One of the important things is the chance to build a team.”

She hired a number of people who had unconventional resumes and no congressional experience, including former students from her Harvard law school classes, such as Ganesh Sitaraman, who also served as an adviser on her presidential campaign, and Dan Geldon, who eventually served as chief of staff to both her Senate office and campaign. “Part of our agenda was about pushing bills, but also getting the executive branch to do more and do better,” recalls Jeremy Bearer-Friend, a professor at George Washington University Law School who led Warren’s tax work from 2015 through 2017. “That meant spending a lot of time thinking through the pitfalls inside agencies, why things were moving slowly, and pressing them to do more.”

Those who rose through Warren’s ranks proved themselves as highly trained professionals as thirsty for “blood and teeth left on the floor” as their boss—and shared her penchant for digging into the details to pave the way for change. Ramamurti, Warren’s former banking counsel now at the NEC, played a lead role in preparing Warren’s infamous excoriation of former Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf in 2016 over the bank’s fake customer account scandal. Her cross-examination is best remembered for its vitriolic one-liners—she pointedly told him he “should resign”—but it was just one of many tactics Ramamurti and his colleagues deployed to force regulators to take action. The effort led to the resignation of not only Stumpf, but also his successor, Tim Sloan, and finally, penalties from the SEC and Federal Reserve.

Julie Margetta Morgan, whom Warren calls “another data nerd” like herself, spent two years working in the Senate digging into the particulars of who carries student loan debt. What she discovered, Warren recalls, was “a job that called for oversight” of the Education Department’s administration of the loan program. They identified an obscure provision in the Higher Education Act called “defense to repayment,” and pushed the department to wipe out the loans of 30,000 students defrauded by for-profit colleges, which it did in 2015. Morgan is now focused on loan debt as a senior counsel at the Department of Education, which is in the midst of studying whether that same provision grants the department the authority to do the sort of mass debt cancellation Warren has advocated for. (Both Morgan and Ramamurti declined to comment for this story.)

Beyond hiring the “smartest, most aggressive people” she can, the former professor still sees herself as a mentor. “My job, while they’re in the Senate office, is to help them sharpen their tools, so when they leave, they’ll be more effective,” Warren tells me, noting she’s deliberate in “help[ing] them find the next job so they can make a difference.” Sometimes, that includes helping them find a new role in government—a place where they can showcase their skills. In 2018, Warren pushed her fellow Senate Democrats to tap Chopra to serve on the Federal Trade Commission, where he championed anti-trust policy. And last April, when Congress created another congressional oversight panel in the wake of yet another financial crisis, then–Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer nominated Ramamurti.

“She realizes that if you’re going to get a big job, you need to show you have experience in governing and politics,” Sperling says. “She encourages her people to get into positions where they can grow from, where they can get a track record for getting stuff done.”

During the Obama years, Warren torpedoed NEC Chair Larry Summers’ expected ascent to the Federal Reserve, and, the following year, led the charge against Antonio Weiss, an executive at boutique asset management firm Lazard when Obama nominated him to serve as Treasury’s undersecretary of domestic finance. That veto power hung over Hillary Clinton’s presidential aspirations, and Warren exercised a quieter pressure on Clinton to avoid similar choices. The way Warren has nurtured her staff is not unrelated to her broader personnel project: It’s one means for preparing a slate of progressive-minded experts to be worthy alternatives.

Warren has been a private but constant voice to the Biden administration on personnel decisions. “I think she’s an enormous resource for the administration,” Damon Silvers, the policy director for the AFL-CIO and a friend of Warren’s. “She’s both a political power that has to be answered at some level, but she’s also a partner with great insight who offers a lot of help.” In Biden’s transition, Warren found a likeminded ally in Ted Kaufman, Biden’s longtime chief of staff when he was in the Senate. Kaufman is best known for briefly taking over his old boss’s Senate seat when Biden ascended to the vice presidency in 2009. Less known is the fact that he later replaced Warren on the congressional panel overseeing the 2008 bank bailout and inherited her staff.

“Elizabeth Warren really knows what she’s talking about, and Elizabeth Warren can pick good staff people,” Kaufman says of the lesson he took from the experience. It was the “unconventional reason,” he tells me, why people who had worked for her were given a “head start” in their consideration for administration posts. His approach to key economic posts across the administration echoes Warren’s priorities. “Something I personally brought up at every personnel meeting we had: Do something about the revolving door, and pick people who are sensitive to inequality and wealth.”

Warren demurs when I ask how much she talks to her former staffers about their new posts. “I don’t want to say anything about that,” she tells me. “I let them do their jobs.” Indeed, they work for the president now, and it’s too soon to say whether these progressive personnel additions are having any influence. They are, after all, just a fraction of the posts across the administration, most of them in crucial, albeit lower-level posts. Though heartened to see several Warren alumni serving Biden, the senator’s allies are closely watching to see who the White House names to some still-open positions—the antitrust jobs in the Department of Justice, for example, and who heads the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, an obscure but influential post that oversees the White House’s implementation of executive actions. Progressives are pushing Biden to choose another Warrenite for the role: Sitaraman, the former Warren aide who’s now a professor of constitutional law at Vanderbilt University.

Warren, meanwhile, continues to be Warren, cutting the new administration little slack. She has already sent letters to a number of Biden’s agencies demanding investigations into one thing or another, including one to the SEC requesting details on how the agency will “crack down on years of distortion in securities markets” that benefit the “wealthy few” in light of the recent volatility in the stocks of GameStop and other companies. As the White House turns its attention to a jobs and infrastructure plan, she reintroduced her wealth tax, her trademark campaign proposal that would tax 2 percent of individuals’ net worth above $50 million, to pay for it. She’s already gearing up for a fight with the president, who conspicuously rejected a wealth tax during his campaign: Last week, Warren hosted a roundtable with vocal progressive activists—including those from the Sunrise Movement, Working Families Party, and others—and liberal wonks to kick off a pressure campaign for her proposal.

Still, it’s a marked change from where Warren sat at the start of the last Democratic presidency. Over dinner at the Bombay Club in April 2009, Larry Summers told Warren, then in charge of the oversight panel, that she had a choice to make. “I could be an insider or I could be an outsider,” Warren recalls in her 2014 memoir. “Outsiders can say whatever they want. But people on the inside don’t listen to them. Insiders, however, get lots of access and a chance to push their ideas.” Insiders also followed one “unbreakable” rule: “They don’t criticize other insiders.”

Warren is now, decidedly, an insider, a status she achieved by breaking that directive when necessary. As for Summers, he wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post last month undermining the White House’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package, warning it could “set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation.” Summer’s attacks drew a swift and sharp rebuke from all corners of the White House. Among the dissenters: Ramamurti. “The president and the administration have a lot of respect for Professor Summers,” he told CBS Radio. “But we disagree here.”