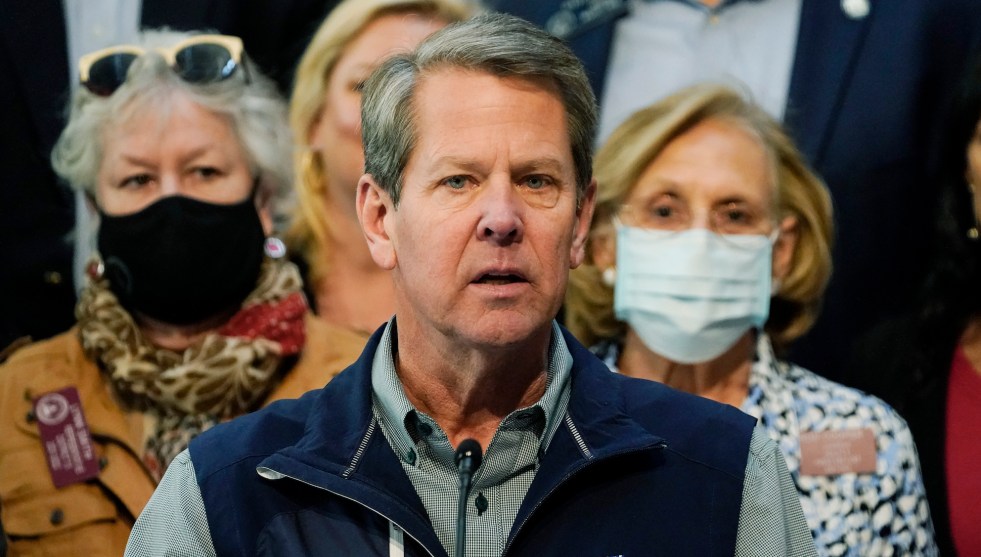

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp speaks at during a news conference on April 3 in Atlanta about Major League Baseball’s decision to pull the 2021 All-Star Game from Atlanta over the league’s objection to a new Georgia voting law. Brynn Anderson/AP

On December 3, 2020, representatives of the Trump campaign testified before the Georgia state Senate and urged it to overturn Joe Biden’s victory in the state. Trump attorney Jacki Picki played a video before a legislative panel purporting to show that “suitcases” of ballots were counted by election officials in Atlanta’s heavily Democratic Fulton County in November after GOP poll monitors had left—a conspiracy theory that went viral in Trump circles but was easily debunked by representatives of Georgia’s Republican secretary of state. Rudy Giuliani told the state legislature to appoint its own presidential electors for Donald Trump because “it’s clear the count you have right now is false.”

The Georgia legislature declined to overturn the will of the voters, but five days later Georgia Senate Republicans released a statement saying they had “heard the calls of millions of Georgians who have raised deep and heartfelt concerns that state law has been violated and our elections process abused in our November 3, 2020 elections. We will fix this.” They vowed that “as soon as we may constitutionally convene” next year they would “reform our election laws” by eliminating no-excuse absentee voting, banning mail ballot drop boxes, and adding new voter ID requirements for mail ballots.

A few weeks later, Trump told Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find 11,780 votes” to overturn Biden’s victory. Just days later, after Raffensperger rebuffed the president, state House Speaker David Ralston said he supported stripping power from Raffensperger’s office and announced he was creating a new Special Committee on Election Integrity tasked with rewriting the state’s voting laws.

The 98-page restrictive voting legislation passed by the Georgia legislature and signed by Gov. Brian Kemp on March 25 was inspired by Trump’s Big Lie and a direct response to it, just like the 361 bills that have been introduced in 47 states this year to undermine voting access. “This is really the fallout from the 10 weeks of misinformation that flew in from former President Donald Trump,” Georgia’s Republican Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan, a critic of the legislation, told CNN on Wednesday, specifically citing Giuliani’s testimony “spreading misinformation and sowing doubt” before the legislature.

Because Trump failed to overturn the 2020 election, the new law was designed to give Republicans an advantage in future elections by targeting the voting methods most used by Democratic constituencies after Biden won the state and Georgia elected two Democratic senators in January. That includes giving the GOP-controlled legislature sweeping new powers over election administration that they did not possess last year.

But now Republicans are trying to rewrite history. Facing widespread criticism of the new law, culminating in Major League Baseball’s decision to pull the All-Star game out of Atlanta, GOP leaders are alleging the law was never intended to suppress votes and was not inspired by false claims of widespread fraud. The bill “expands access to the ballot box,” Kemp said last Friday. When MLB moved the All-Star game to Colorado, many prominent Republicans, including Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.), ludicrously claimed that Colorado’s voting laws—among the most accommodating in the country—were more restrictive than Georgia’s. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell went so far as to call accusations of voter suppression “the big lie” instead of Trump’s conspiracy theories about a stolen election.

It’s true that a few parts of the bill will expand voting access, most notably a provision that requires more days of weekend voting, which will not affect large counties in the Atlanta area that already offered multiple days of weekend voting but will create more voting opportunities for rural counties that lean Republican. It’s also true that some of the most radical proposals that advanced through legislative committees or passed one chamber of the legislature—such as ending no-excuse absentee voting, cutting Sunday voting, and eliminating automatic voter registration—did not become law, likely because they were highly popular voting methods and eliminating them would have hurt GOP constituencies as well.

But these concessions are dwarfed by all the ways the 98-page bill does restrict voting access—a fact that has become overshadowed during debates over the bill in recent days. At least 16 key provisions will make it harder to vote in Georgia, the New York Times found. The new legislation makes it a crime to give voters food or water while they’re waiting to vote, sharply limits mail ballot drop boxes, adds new voter ID requirements for mail-in ballots, rejects most ballots that are cast in the wrong precinct, gives voters less time to request mail ballots, prevents election officials from sending mail ballot applications to voters, and allows right-wing groups to challenge the eligibility of an unlimited number of voters.

Thread – all the ways Georgia legislation makes it harder to vote:

-makes it crime to give food & water to voters in line

-severely limits mail ballot drop boxes

-allows GOP legislature to appoint majority on state election board & suspend county election officials

1/4

— Ari Berman (@AriBerman) April 2, 2021

It also makes it more difficult for counties to run elections by prohibiting them from accepting donations from nonprofit groups, which were used in 2020 to add more voting sites and drop boxes, and bans innovations like mobile voting buses that made voting more convenient. And, following the victories of Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock in the January runoffs, it dramatically reduces the time for runoff elections to be conducted, cutting them from nine weeks to four weeks after the general election.

The cumulative impact of these changes will make it harder for voters to cast a ballot, harder for organizations to mobilize voters, and harder for election officials to run smooth elections.

And if all of that fails to help Republican candidates, who benefit when the electorate is smaller and whiter, the new law allows the GOP-controlled legislature to appoint a majority of the state elections board, which oversees voting rules in the state. It also removes the secretary of state as chair and voting member of the board, after Raffensperger defended the integrity of the election and stood up to Trump. The state board, in turn, can take over up to four county election boards it deems underperforming, raising the possibility that election operations in heavily Democratic areas like Fulton County could be run by officials accountable not to the voters but to the heavily gerrymandered GOP legislature. These boards could decline to certify results and disqualify voters in close elections won by Democrats—exactly the scenario Trump tried to pull off in 2020.

"The real purpose here was to intensify control over how every aspect of elections are run in Georgia. So when there are close elections in the future, which they know there will be, they will have unprecedented power to challenge the election results…" @AriBerman pic.twitter.com/NBPms3hmgj

— Maddow Blog (@MaddowBlog) March 26, 2021

It’s possible, as Nate Cohn wrote in the New York Times on Saturday, that all of these new voting restrictions, combined with the GOP’s increased power over election administration, won’t lead to widespread voter suppression and could produce a backlash that helps Democratic candidates. But in a state like Georgia, small changes around the margins are enough to swing a close election. Because Trump couldn’t get those 11,000 votes, the GOP-legislature is trying to make it easier for Republicans to find them in future elections.

The new law may not be “Jim Crow on steroids,” as Joe Biden claims. But it almost certainly is “Jim Crow Lite,” to use the words of Jonathan Chait. And regardless of the eventual impact, its entire passage was predicated on a lie—which makes it a lot harder to take seriously the claims of its proponents now.