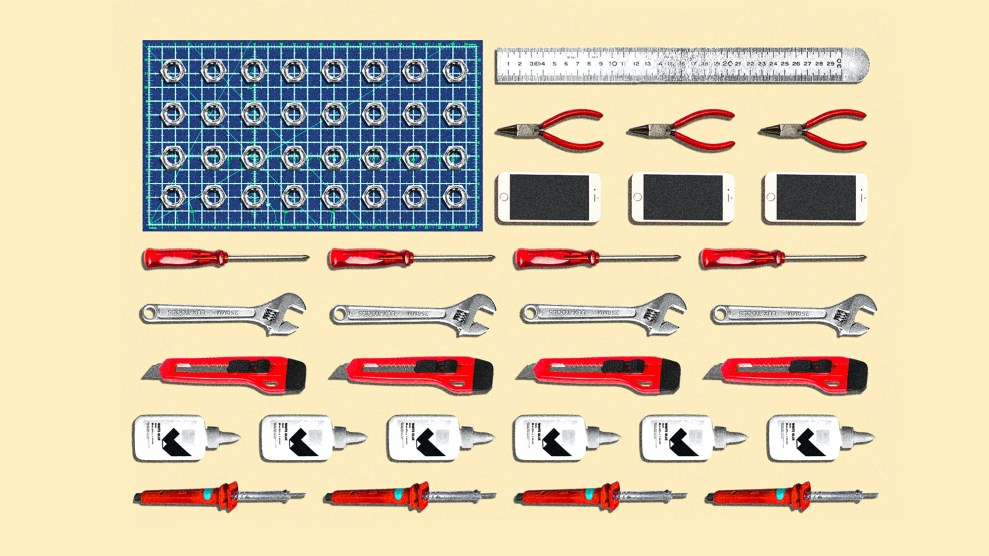

Amelia Bates/ Grist

This story was originally published by Grist and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

For the past several years, as state legislators across the country have held hearings to consider “right-to-repair” bills that would make it easier for consumers to fix their electronic devices, lobbyists representing manufacturers have shown up to repeat the same arguments over and over: Letting people fix their own stuff is too dangerous. It creates cybersecurity risks. It infringes on intellectual property. It won’t help reduce electronic waste.

But while it remains to be seen whether these arguments will win over any of the dozen state legislatures currently considering a right-to-repair bill, one authoritative body isn’t buying them at all: the Federal Trade Commission.

Last week, the FTC released a long-anticipated report to Congress examining the repair restrictions facing consumers, along with a summary of arguments for and against those restrictions. Its conclusion was stark: There’s “scant evidence” to support manufacturers’ justifications for restricting repair, while the solutions repair advocates have proposed are “well supported” by their testimonials. Advocates say that compelling companies like Apple and Tesla to release parts, manuals, and diagnostic information needed for repair will make fixing broken devices faster and more affordable. Ultimately, this will encourage us to maintain our stuff instead of replacing it, resulting in less environmental harm and electronic waste.

With the release of the report, the FTC has signaled that it plans to step up its efforts to enforce laws aimed at preventing manufacturers from restricting repair. But the symbolic nature of the report may be more significant than whatever punitive actions the agency takes next.

The right to repair movement—which promotes the idea that everyone should to be able to repair the devices they own however they want, whenever they want—has “just been given a huge shot in the arm,” said Gay Gordon-Byrne, the executive director of The Repair Association, a right-to-repair advocacy group.

Kerry Maeve Sheehan, the US policy lead at the repair guide site iFixit, agreed. “[F]inally a government agency is saying what we’ve said all along—that manufacturers’ justifications for imposing repair restrictions aren’t backed by evidence,” Sheehan wrote in an email.

The report traces its origins back to a July 2019 workshop the FTC held to explore how manufacturers restrict repair of their devices. The workshop brought together right-to-repair advocates, groups representing manufacturers of everything from gaming consoles to home appliances, and independent researchers. It invited everyone to submit empirical research on the repair landscape. A year later, Congress directed the FTC to issue a report summarizing its findings, with a focus on cell phone and automobile markets.

Those findings amount to nothing less than a wholesale rejection of the anti-repair arguments advanced by lobbyists not just for cell phone and car companies, but home appliance industries, medical device makers, and more. In its 56-page report, the FTC lays out common manufacturer arguments in favor of restricting repair. For every single argument, the Commission reaches a similar conclusion: There’s little evidence to support it.

Take safety concerns. Companies will often argue that restricting access to the information and materials needed for repair prevents consumers, or mechanics that lack sufficient training, from hurting themselves. For instance, people attempting to swap the lithium-ion battery inside their phone might accidentally puncture it, causing the battery to experience a “thermal runaway event”—or in layman’s terms, overheat and explode. But aside from a single 2011 incident involving a cell phone that experienced a thermal runaway event on a plane after a faulty unauthorized repair, manufacturers provided the FTC no evidence of injuries tied to independent repair. Nor did they furnish any data demonstrating that their authorized repair shops are more careful. Meanwhile, decades’ worth of evidence from the auto repair industry shows that even the most dangerous consumer products can be safely repaired by an independent professional.

Other arguments followed a similar pattern. Consumer technology manufacturers told the FTC that handing a device that contains sensitive personal data, like a laptop, over to an independent shop can create security risks. But they failed to provide evidence that independent repair businesses are more likely to mishandle that data than the manufacturer. The Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers told the agency that manufacturer-backed repair providers help uphold the “brand reputation” of companies, but it didn’t demonstrate that consumers were less satisfied with repair jobs conducted by independent mechanics. And while Microsoft argued that design choices that limit device repairability—such as using glue instead of screws to secure batteries and screens in place—are driven by consumer preference, empirical research has shown that consumers also care about the longevity and repairability of their devices.

The FTC was far more sympathetic to repair advocates’ claims that manufacturer barriers make repairs take longer and cost more. It also concurred with advocates that increasing access to repair will have environmental benefits, from reducing the energy use associated with making new devices to slowing the tide of toxic electronic waste. Industry lobbyists say that they have already implemented take-back programs that have driven e-waste levels down, but many experts say this argument is misleading. While the total volume of e-waste is declining in the US as electronics get smaller and lighter, researchers say that the complexity of today’s smartphones, tablets, and flat-screen TVs makes them harder to reuse and recycle. Sheehan of iFixit added that many state electronics recycling laws cover “a limited scope of products,” including old, bulky cathode-ray tube televisions but not newer technologies like smart fridges.

Overall, the FTC concluded that the repair barriers manufacturers create have “steered consumers into manufacturers’ repair networks or to replace products before the end of their useful lives” without any decent justification.

“This is a huge tool for us,” Nathan Proctor, who heads the right-to-repair campaign at the advocacy nonprofit US Public Research Interest Group, said of the new FTC report. “We certainly are going to use this report to advocate for state right to repair laws.”

Indeed, the report comes as dozens of state legislatures have recently considered bills that would make it easier to repair small electronics, home appliances, and farm and medical equipment. The pandemic has helped fuel those bills by spotlighting the “digital divide” between wealthier, whiter, more urban communities, which have more access to the electronic devices they need to work and learn remotely compared with lower income, rural, and communities of color. Advocates argue that making it easier to fix broken devices could narrow that divide, since repairing a phone or laptop tends to be a more affordable option than replacing it. The pandemic has also revealed that letting manufacturers restrict the repair of specialized equipment like ventilators can be a matter of life and death.

While advocates continue to push for the right to repair to be enshrined into law, the FTC may start cracking down on companies that violate existing laws. The Commission’s investigation into repair restrictions came about, in part, due to its concern over companies violating the so-called “anti-tying provision” of the 1975 Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, which makes it illegal for manufacturers to void warranties if consumers go to an independent shop or use an off-brand part to fix their devices. If you’ve ever been told by, say, the company that made your phone or printer that opening it up and fixing it yourself will void your warranty, you know this law is not being aggressively enforced.

“People have this idea in their heads that they’re somehow violating a contract with a manufacturer” if they fix their device, said Proctor. “And this is cultivated consistently and aggressively by manufacturers.”

But the Wild West days of companies making up their own warranty rules may be numbered. The day its report came out, the FTC’s official Twitter account called on members of the public to send in a report if they were told their warranty would be voided by an independent repair.

A spokesperson for the FTC told Grist that in addition to “pursuing appropriate law enforcement options” with respect to the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, the FTC would be looking into other legal and regulatory avenues to support independent repair “consistent with our statutory authority” and educating consumers about their rights.

“The Commission also stands ready to work with legislators, either at the state or federal level, in order to ensure that consumers have choices when they need to repair products that they purchase and own,” the spokesperson said.