Spencer Platt/Getty

It is natural, on a day like this, to think about the deer.

In late autumn of 2016, a white-tailed buck took up residence at Jackie Robinson Park in Harlem. Locals dubbed him J.R., after the park he was found in, or Lefty, because he was missing most of his antler on that side. It was Manhattan, where such megafauna are rare, so Lefty became a mini-celebrity. But also, it was Manhattan. Lefty, like Mucky the Gowanus Dolphin before him, was a long-term impossibility, a guest living beyond the practical means of his environment, and so several weeks later, when Lefty escaped from the park into the grounds of a nearby housing complex, the city announced that it would have to put the deer down.

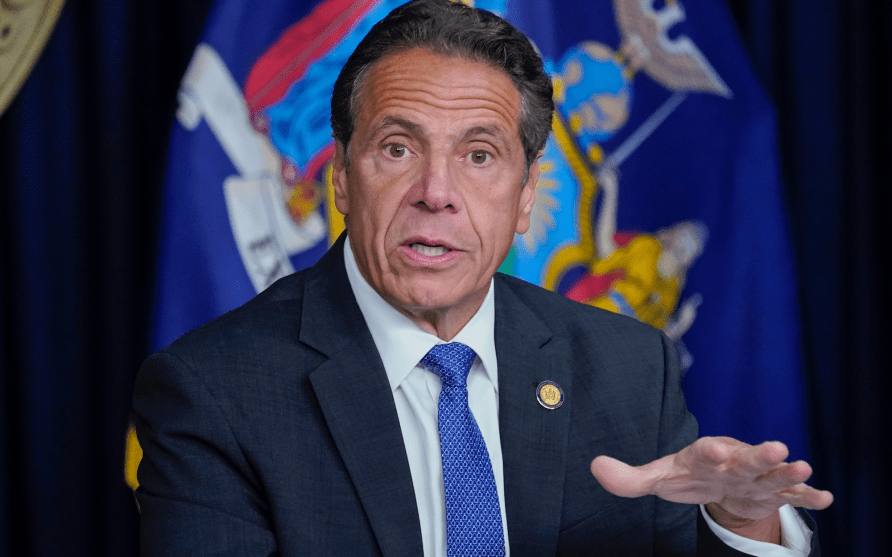

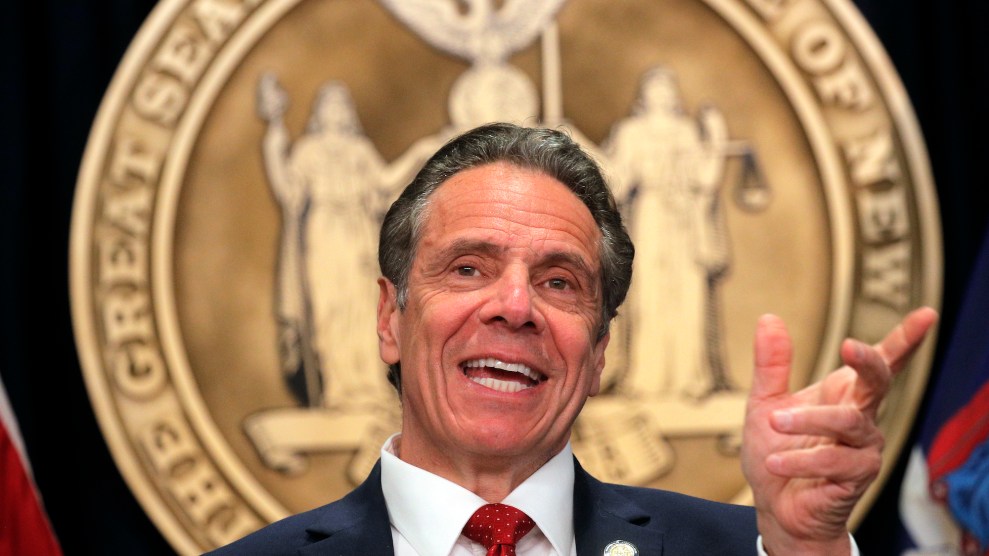

That’s when Andrew Cuomo stepped in. Although the city had acted on the recommendations of the state’s own conservation agency, which had a policy of discouraging deer relocation, the New York governor swooped in to offer sanctuary to the buck. “We want to do everything we can to save the Harlem deer,” he announced. “We have told the city that the feds or we can transport it upstate today.” The city and the state went back and forth on this for two days, until finally, Lefty died in custody—evidently from all the stress.

It’s hard to conjure a political fight less consequential. Why was the governor of New York wading into this? Why was this even a Thing? What exactly were “the feds” supposed to do? There was no reason it ever had to happen at all, except that it offered Cuomo a chance to humiliate New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio—which meant that there was no way in hell the governor was staying out of it. Brutish and unnecessary demonstrations of power, after all, are how Andrew Cuomo says hello.

Cuomo announced his intent to resign on Tuesday, one week after a state investigation detailed a years-long campaign of sexual harassment and retaliation against state employees. The decision to turn the reins of the state over to current Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul, on August 24, came after a sheriff in Albany announced that one of the women Cuomo allegedly assaulted had filed a criminal complaint against the governor and as the state legislature moved forward at last with impeachment. As he spoke to the press, Cuomo himself sounded surprised at the turn of events—perhaps that’s because the reality of who he was was in plain sight for such a long time.

For years the kind of domineering behavior that precipitated Cuomo’s downfall was misconstrued—or cynically spun—by many allies in the Democratic Party and in the press as effectiveness. He was obsessed, not unlike another Queens-born legacy, with the optics of control. As the saga of Lefty demonstrated, Cuomo relished playing the part of the state’s alpha, shoving the dweeby de Blasio into a locker at every opportunity, but always with a chiding note, as if to say that he was only doing this because the city needed it. Cuomo wanted to come off as the adult forever stepping in to clean up someone’s mess. Lefty, like all of us, was just caught in the middle.

But as Rebecca Traister detailed in a brilliant New York magazine profile earlier this year, Cuomo’s power plays reflected something deeper and darker about him. The governor’s “tough-guy routine has in fact worked to obscure governing failures,” Traister wrote. “It is precisely what has permitted Cuomo and his administration to spend a decade being…both mean and bad at their jobs.”

This should be sort of obvious—I mean, of course obsessively undercutting the mayor on everything from the deteriorating subway to a deer was not conducive to good governance. His efforts to undercut the state legislature were likewise a matter of public record. But the dissonance between the perception and the reality was never sharper than it was during the pandemic, when Cuomo reached his greatest heights of political celebrity at the same time his policy choices were exacerbating suffering on the ground.

Like Trump, he turned his daily coronavirus briefings into a reality show that obscured his own government’s response. Cuomo cracked jokes about his daughter’s boyfriend (this was the sitcom-dad version of the alpha character) and even sold posters depicting illustrations of him and his inner circle (top aide Melissa DeRosa, last seen in the AG’s report attempting to leak the personnel file of a Cuomo accuser, appears as “Magnificent Melissa”). He was performing the part of a crisis manager in his emergency jacket and authoritative tone—a gruff presence granted nightly opportunities to hone his image in softball interviews with his brother, Chris, an anchor on CNN who later, behind the scenes, helped him workshop his response to the sexual harassment allegations.

The idea of Cuomo’s masterful handling of the pandemic was always just projection—and there are few things more dangerous than the illusion of competence. As Cuomo played the part, his administration was attempting to cover up the death toll behind his disastrous decision to send COVID patients into nursing homes. As New Yorkers were dying in droves, he inked a $5 million book deal about the lessons he’d learned during the pandemic, which members of his administration proceeded to help him write. When a member of the State Assembly tried to blow the whistle on Cuomo’s mismanagement, Cuomo threatened his career.

It was that last threat that triggered everything else—more people began coming forward to talk about their experiences with Cuomo, including Lindsey Boylan, a former staffer who said the governor had sexually harassed her, which in turn led to Attorney General Tish James’ investigation, which finally prompted some of Cuomo’s most important allies, such as Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, to pull their support.

But it’s important to remember that lots of people not only saw through Cuomo’s facade, but called him out a long time ago. Cuomo spent years cartoonishly abusing his powers in plain sight—his machinations and bullying were, to borrow from another avatar of hubris, Known Knowns. In 2014, Zephyr Teachout, a Fordham law professor, pulled 33 percent of the vote in a gubernatorial primary while largely running against Cuomo’s shuttering of the Moreland Commission—which had been formed to investigate corruption in his administration. In 2018, Cynthia Nixon, a much-better-known actress and progressive activist, accused Cuomo of being a misogynistic bully who would rather pick fights and bluster than fix the public institutions—such as the New York City subway—he was responsible for maintaining:

There is a clear pattern of Andrew Cuomo ignoring reports of sexual harassment against his top staff and allies. He even promoted men who he knew had a history of misconduct. New York can do much better than reelecting a hypocritical governor who ignores the victims. pic.twitter.com/fW5pnTshTD

— Cynthia Nixon (@CynthiaNixon) May 30, 2018

Cuomo’s response to these women challenging his authority was revealing: more of that total macho bullshit. When Cuomo crossed paths with Teachout at a parade, he refused to even acknowledge her presence. Afterward, he started a sham political movement called the Women’s Equality Party, in an attempt to curb the influence of the progressives who had crossed him. Four years later, his aides dismissed Nixon as little more than a flighty consumer of cosmopolitans.

It was never a tough act to figure out, but it wasn’t just an act; it was also a tell.