Adam Fagen/Flickr Creative Commons

According to a story from the New York Times earlier this week, the Biden administration is pushing stats based on an “unconventional” methodology to show that American billionaires aren’t paying their fair share of taxes.

The income tax is generally progressive. Contrary to popular belief, most top 1 percent earners don’t pay lower income-tax rates than Warren Buffett’s proverbial secretary. Their rates tend to be much higher, though America’s top 400 earners have finagled a way to pay about the same average income tax rate as people in the 80th income percentile.

Under federal rules, meanwhile, a person can have insane wealth and little reportable income. A guy like Buffett, whose net worth is largely tied up in stock and private investment holdings, has no need to take a paycheck. In fact, as ProPublica revealed, based on leaked IRS data, Buffett and lots of his top 400 peers—Bezos, Gates, Musk, Soros, Zuckerberg, etc.—avoid income almost entirely, so there’s very little to tax. They can simply borrow money against their vast investment holdings and live off that instead, paying a few percent in interest instead of 37 percent—the top rate the IRS charges on regular work income.

What makes the administration’s new math “unconventional” is that it counts unrealized capital gains—paper profits—as income when calculating effective income tax rates for the very rich. That’s dicey, because those gains are not presently viewed by the IRS as taxable income—only when you sell an asset are you taxed on the profit. The rates on long-term capital gains—profits on the sale of investments held for a year or more—are 15 percent or 20 percent, depending on the size of the profits.

Some economists, notably UC-Berkeley’s Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, have argued that the federal government should tax paper profits. But that doesn’t seem remotely likely to fly with this, or perhaps any, Congress. As things stand, Biden had hoped to nearly double the top capital gains rate, from 20 percent to 39.6 percent—the same maximum rate Biden wants to restore on regular wage income.

Treating capital gains the same as wages for tax purposes would go a long way toward reducing America’s yawning wealth divide and narrowing the racial wealth gap, too. But congressional Democrats don’t have the stomach—nor the votes. Stuck with a 50-50 split in the Senate and a couple of recalcitrant moderates, they have instead proposed to bump the top capital gains rate from 20 percent to just 25 percent.

Even that fairly modest increase faces resistance from wealthy and powerful executives and investors, the trade groups that represent them (like the Business Roundtable and the US Chamber of Commerce), and the financial firms that service the needs of the ultrawealthy by maximizing their investment returns and minimizing their taxes.

Another wealth-sustaining trick that’s unlikely to die is the “step-up in basis” rule, which I explain in detail here. Basically, it means that the “cost basis” of my invested assets—the amount I paid for them originally—resets to the assets’ current market value when I die, so that neither I nor my heirs will ever pay a capital gains tax on those profits. As blatantly unfair as this is to people who work for a living, there are wealthy folks on both sides of the aisle who want to keep the perk intact.

What strikes me about all of this is that the administration didn’t even need tricky math to show that the billionaires aren’t paying their fair share. As Saez and Zucman point out in their 2019 book, The Triumph of Injustice, if you combine all of the taxes we pay—business, property, consumption, and estate taxes—the very richest pay less as is. Substantially less.

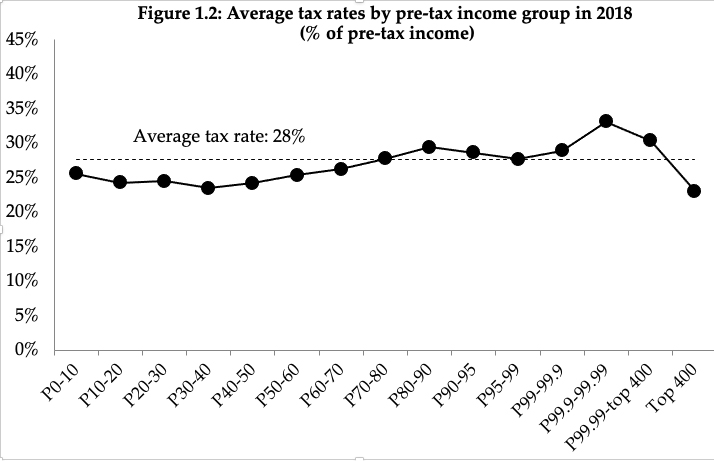

When federal, state, and local taxes are factored in, we end up with something conservative politicians have long called for—a flat tax. In 2018, as shown above, the average combined tax rate for all Americans was 28 percent. The working class, which Saez and Zucman define as the bottom 50 percent of earners, were compensated an average of $18,500 a year, and they paid about 25 percent of that in various taxes. The average combined tax rate rises slowly as we climb up the income ladder, hitting about 28 percent for the 90th through 99th percentile earners, and most of the 1 percent. Top 0.1 percenters and up, most of them, paid between 30 percent and 35 percent overall. But the top 400? They paid less than the poorest Americans: just 23 percent.

These are the scoundrels we need to watch out for.