A Chinese power plant.Getty Images

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The pledge by China’s president, Xi Jinping, on Tuesday to cease building new coal-fired power projects outside the country will be welcome news to environmentalists around the world. It came on the anniversary of Xi’s unilateral pledge for China to reach carbon neutrality by 2060. Last year Xi also promised that Chinese emissions would peak by 2030.

“China will step up support for other developing countries in developing green and low-carbon energy, and will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad,” Xi said in a pre-recorded video address at the annual UN general assembly.

Xi is personally invested in the climate agenda. Since he came to power in 2012, Beijing has been taking more visible steps in tackling its own environmental problems such as pollution. It has been extending its influence abroad, too, by joining international initiatives such as the 2015 Paris climate agreement—a pledge that Donald Trump pulled the US out of four years ago but which Joe Biden has rejoined. And unlike in some countries, there is consensus among China’s political elite that the climate crisis is real.

Inside China there has been growing awareness among citizens about the impact of the climate crisis. This summer’s devastating floods in Henan province illustrated to many people the consequences of inaction on the climate emergency. Jia Xiaolong, the deputy head of the national climate centre, told China News Agency that the heavy rainfall in Henan occurred “against the backdrop of global warming”.

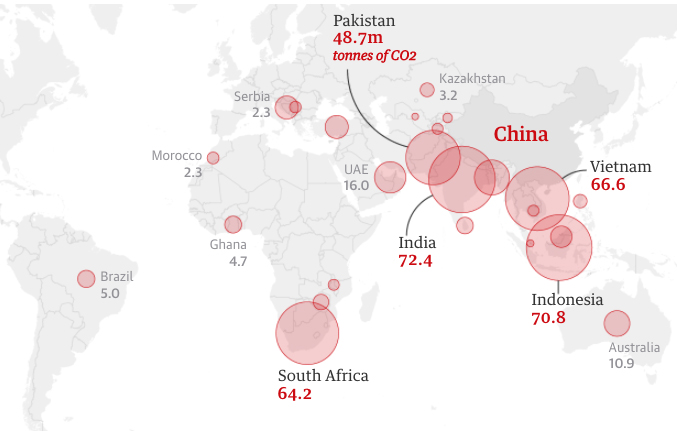

There’s little doubt about how significant China’s promise to stop funding overseas coal-fired power projects is. Until recently, China, Japan and South Korea accounted for more than 95 percent of all foreign financing for coal-fired power plants, according to Georgetown University. Japan and South Korea promised to cease such operations early this year.

But the slew of promises from the trio in recent months is “low-hanging fruit,” according to Geall. The falling price of renewables in recent months means the economic case for coal is worse than ever. Few countries want to be lumbered with new coal fleets. “China will, of course, need to go further in curbing its domestic coal production and consumption—which it has room to do under its 14th five-year plan and as part of the 2060 goal,” he said.

Thomas Hale, of the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government, agreed. He said coal remained very much alive within China, which is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter. After Xi’s pledge, all eyes would focus on China’s domestic plans. “Ultimately, the single most important question for the future of life on planet Earth is how quickly China can shut its thousands of coal facilities,” he said.

But China’s historical reliance on coal is driven by the need to keep economic activity going. Ultimately, how China is to reduce its coal dependency will be determined by the transition of the economy itself. It is what Beijing has promised to do, but it is proving to be a difficult task. China’s provincial governments approved the construction of 24 new coal power projects in the first half of 2021, including three large-scale power plants, according to Greenpeace, although that represented a decline on numbers approved in 2020.

While international commentaries have been heavily focused on the economic ramification of the potential collapse of Evergrande, China’s second largest property developer, in recent weeks, Hale thinks this crisis may ultimately be of more significance to the climate.

“If that building crisis helps push the Chinese economy away from a debt-fueled growth model, it could be the biggest climate development of the year. If instead it shows just how deeply that model is entrenched in China’s political economy, then we will need to treat China’s climate ambitions with greater skepticism,” he said.