On a glorious Saturday morning in October, about 75 people are gathered inside an airy warehouse on the wooded grounds of Foam Works, a local insulation company on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The mostly white, middle-aged crowd sports Trump 2024 hats and T-shirts extolling the Second Amendment, but no masks. Parked on the grass outside are cars scrawled with window paint warning about the evils of the “New World Order.” They’ve come from around the region for a “citizen summit” organized by a Maryland state trooper and the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA) to educate “we the people” about the Constitution, and how a county sheriff could help them “resist government overreach.” CSPOA’s founder Richard Mack came from Maricopa County, Arizona, to headline the all-day seminar.

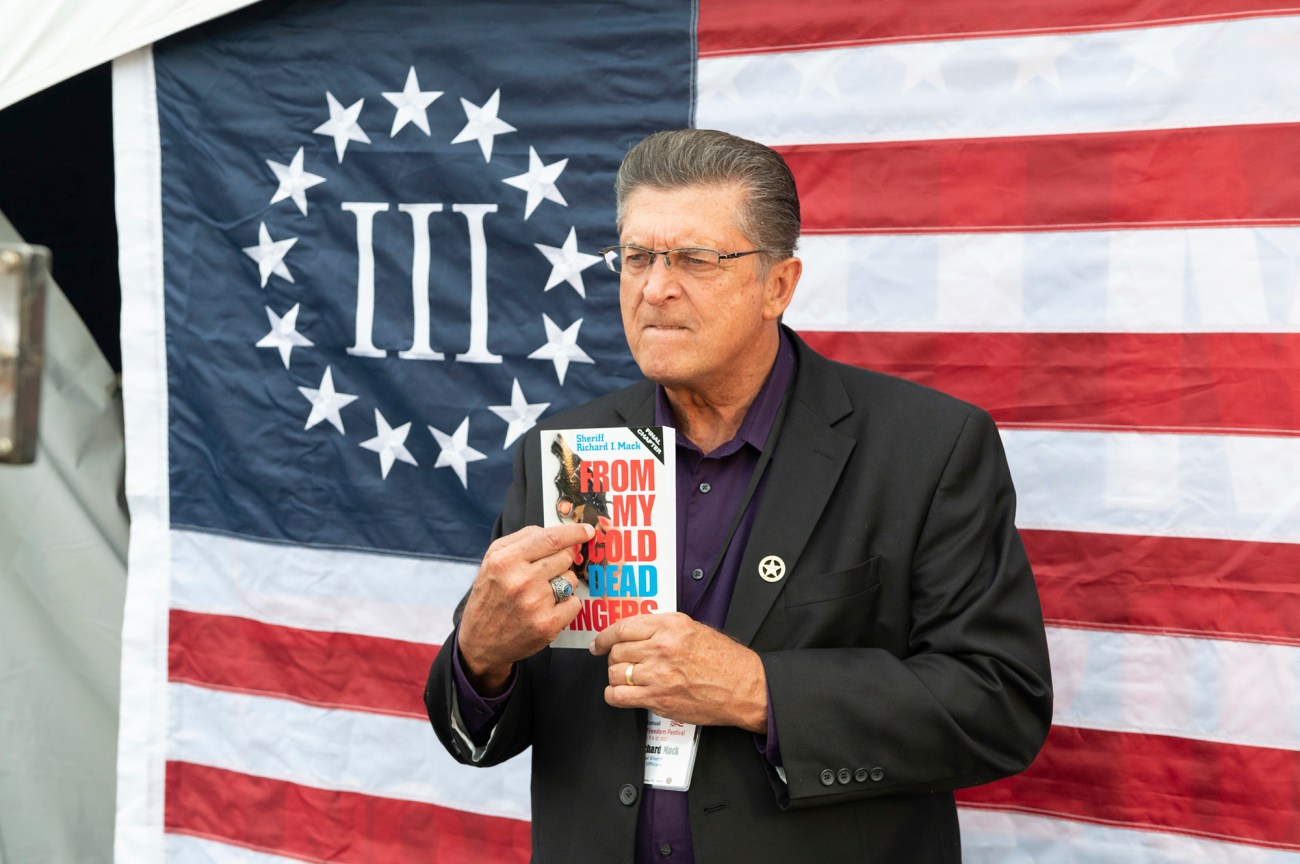

As attendees mill about grabbing donuts and coffee, Mack genially chats with them and hawks his self-published books, including The County Sheriff America’s Last Hope and The Proper Role of Law Enforcement. Tall and tan, at 68, Mack has the look of an aging game show host and carries himself with the self-assurance of a minor celebrity. He has decades-long deep ties to militia and extremist groups. He even wrote a book with his friend Randy Weaver, the white separatist whose wife and son were killed by federal agents during an 11-day standoff at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in 1992, called Vicki, Sam and America: How the Government Killed All Three.

Mack’s organization, CSPOA, is made up of hundreds of elected county sheriffs and their supporters who promote the idea that sheriffs have the power to refuse to enforce laws they deem to be unconstitutional—like, say, virtually all gun control laws. Mack believes that county sheriffs have more power than the president of the United States.

“He’s had more success in bringing anti-government ideas to law enforcement than anyone else,” says Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism who recently published a research report on Mack and CSPOA.

Recently, CSPOA members have made headlines for refusing to enforce state mask mandates and they’ve played a leading role in some communities challenging the results of the 2020 presidential election. A 2016 CSPOA “sheriff of the year,” Michigan’s Dar Leaf, went so far as to try to recruit other “constitutional sheriffs” to help him try to seize Dominion voting machines last year.

Mack has been a familiar face on the far-right extremist circuit since the mid-1990s, when he first emerged as a Second Amendment activist. He has been doing events like the one in Maryland promoting the supremacy of the county sheriff for more than a decade. In 2011, a group called Patriots of Gillespie County, in Fredericksburg, Texas, hired him to start CSPOA to focus on recruiting law enforcement into the patriot movement. The group moved him and his wife to Texas, where he also made an unsuccessful run at unseating the incumbent GOP congressman, Lamar Smith. But since the beginning of the pandemic, he tells me, he’s been in high demand as sheriffs have been asked to enforce the “tyranny of the good intentions of our leaders” and their public health mandates.

What’s also new for Mack, and especially troubling to civil rights advocates, is that this year, the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement (TCOLE) approved CSPOA to provide official trainings that officers need to maintain their proficiency certificates. So have 10 other states, according to Mack, including Virginia, Montana, and South Carolina. This is happening even as the FBI has been warning for years that extremists have been trying to infiltrate law enforcement to pursue their ideological goals. Those efforts became apparent at the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol; at least 20 current or former law enforcement officers have been arrested on charges relating to the riot, along with more than 20 members of the far-right militia group, Oath Keepers, a group Mack was a longtime board member of until 2015. Yet TCOLE has empowered CSPOA to train law enforcement across the state.

“There is a huge problem already with hate groups organizing within law enforcement,” says Jonathan Smith, who oversaw police reform efforts at the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division during the Obama administration and is now the executive director of the Washington Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs. “We’ve seen repeated waves of it in the past 10 years, with the recruitment of law enforcement officers on the internet. For this to move from the sort of the dark corners of the internet to officially sanctioned trainings from one of the largest states is really frightening in my view.”

When Mack takes the podium at FoamWorks, he laments that he’d invited all 24 Maryland sheriffs to attend the event, but only Frederick County Sheriff Chuck Jenkins has shown up. Jenkins is a Fox News regular, hardcore immigration foe and one of today’s speakers. In January, he had to issue an apology and his department paid $125,000 to settle a lawsuit accusing his office of engaging in racial profiling and wrongful detention of a Latina woman. “If this event would have been in Texas,” Mack says, “we would have had 75 or 80 sheriffs here.”

He then tells the well-honed story about how, as an elected sheriff in Graham County, Arizona—he was a Democrat at the time—he hadn’t set out to become a national gun activist. In fact, until he was elected sheriff, he’d never even owned a firearm. “I never could figure out why you’d want to go hunting when you could go play golf,” he says as the crowd laughs appreciatively. But in 1994, Congress passed the Brady Bill, a landmark gun control measure that would have required him, under threat of criminal penalties, to conduct background checks on people trying to buy handguns. He was outraged and rang up the National Rifle Association.

Soon Mack became the first sheriff to file suit over the Brady Bill. “Of all the people who sued Bill Clinton, I was the only one who did it on a non-sexual matter,” he deadpans. His case went to the US Supreme Court, which in a 1997 decision written by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, found that the gun law violated the state’s rights provisions of the 10th Amendment and ruled in Mack’s favor. He now sells annotated copies of the decision at his speaking events. (“You know how much this cost me?” he asked me earlier, waving one of the pamphlets. “$400,000!” referring to the legal fees in the case. “But you can have three for $5.”) The case set him on his current path as a regular feature of the far-right extremist talk circuit.

His spiel in Maryland is an odd jumble of civics lesson, Thomas Paine quotes, and dated pop culture references. According to Mack, sheriffs have the power to kick IRS or USDA agents out of a county, where he says federal officers have no jurisdiction. To drive home his point about why citizens might need the local sheriff to do this, he shows the Maryland audience a news clip about a man whose door had been kicked in by agents serving a US Department of Education warrant to collect a student loan debt.

At one point he plays a clip of Angela Bassett in the 2002 made-for-TV movie The Rosa Parks Story to illustrate why he believes that a “constitutional sheriff” would never have kicked Rosa Parks off that famous bus. Instead, he would have escorted Parks safely home, thanked her for her bravery, and ensured that her husband had a loaded gun in the house. Despite his fondness for invoking Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. in his public appearances, Mack has won few fans among civil rights activists, largely because of comments like the one in his 1996 book, From My Cold Dead Fingers: Why America Needs Guns, in which he wrote that “the Reverend Jesse Jackson types and the NAACP have done more to enslave Afro-Americans than all the southern plantation owners put together.”

Over the course of 90 minutes, he covers everything from sex scandals at the Drug Enforcement Agency to the Agriculture Department’s persecution of the Amish for selling raw milk. He rails against the tyranny of government requiring “face diapers” and vaccine mandates and claims hospitals have fabricated statistics about the number of people who have died of COVID. He doesn’t mention that he had the disease himself in December. (“I thought I was going to die,” he tells me later.) He tells the group that his presentation is very similar to what he teaches in the sanctioned continuing ed classes for law enforcement, minus some deeper dives into things like civil asset forfeiture.

“People who say I’m radical, I’m an extremist, I’m dangerous, I promote violence,” Mack preaches to the crowd. “Let’s make this very clear right now: I had never promoted violence or advocated violence. Ever. In 20 years of law enforcement, I never even slapped or slugged another human being. I never shot anybody or maced anybody. I never hit somebody with my nightstick. I’ve never attacked, hurt or maimed any human being ever. But yet the Southern Poverty Law Center has me down as a domestic terrorist!”

He looks over at Sheriff Chuck Jenkins, who’s shaking his head. “Oh, you’re one, too?” Mack asks with a laugh. “Congratulations! Anybody who believes in the Constitution, you’ll make their list!”

“There is a God! Our rights come from Him!” the crowd chants. “The purpose of civil government is to protect God given rights!”

Leading them is Michael Peroutka, a Maryland debt collection lawyer and founder of the Institute on the Constitution (IOTC), which has teamed up with Mack to provide educational content for today’s summit. Peroutka was previously a board member for the League of the South, a neo-confederate secessionist group that helped organize the deadly 2017 white nationalist Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. In 2014, while running for the Anne Arundel, Maryland, County Council, video emerged of him leading attendees at the league’s annual convention in singing “Dixie,” which he called the “national anthem.” He quit the board and won the council race.

Peroutka is joined at the citizens’ summit by two IOTC colleagues. There is Jake McCauley who previously worked in the homophobic rock ministry of Bradlee Dean, the Minnesota anti-LBGT activist. Like Dean, McCauley has suggested that “homosexuals” are responsible for most cases of child molestation in the US. The other is senior IOTC instructor Pastor David Whitney, who has served as the chaplain for the League of the South’s Maryland chapter and appears in videos IOTC sells, such as “Weighing in on Anchor Babies.” Before Mack speaks, Whitney leads the group in prayer.

Cops have been fired for associating with the League of the South. But Peroutka and his group have been helping Mack train law enforcement in state-sanctioned trainings in Texas.

Peroutka tells the crowd that he always teaches sheriffs and other law enforcement that “the purpose of civil government is not to make you wear a seatbelt.” He, too, teaches that the sheriff has unilateral power to decide which laws should be enforced. “When a peace officer refuses to enforce an unconstitutional enactment or order,” he explains, “a peace officer is not breaking the law but upholding the law.”

“And who is empowered to decide what the law is?” he continues. “The sheriff. The source of law is not what some judge wrote last week. Law comes from God.” He continues to unspool his Taliban-level legal analysis to the admiring crowd, who gave him a standing ovation when he took the podium. “Unjust laws are not laws,” he says. “In America, if it violates the Bible, it’s not law.” By that reasoning, he explains, Roe v. Wade can’t be law because of Exodus 20:13, which says, “Thou shalt not murder.”

“Roe v. Wade isn’t law,” he noted. “It’s just an opinion.”

In fact, Peroutka’s interpretation of the Constitution isn’t law and just opinion. “I can’t imagine teaching law enforcement that Jesus wrote the Constitution,” says Zoe Nemerever, a political scientist at Texas Tech University who has studied the constitutional sheriff movement. “The sheriffs have no stated power in the federal Constitution to be interpreting which laws are constitutional and which laws or not. That’s what the Supreme Court does.” Nonetheless, Peroutka’s talk in Maryland is virtually the same as the one he has given to law enforcement in Texas this year, Mack tells me.

Peroutka, who did not respond to requests for comment, is only one of several controversial partners Mack has teamed up with over the years, each in their way bold-face names in extremist circles. In late June, Mack held an event at Flathead County, Montana, attended by his friend and former co-author, Ruby Ridge’s Weaver—a man who once sold sawed off shotguns to an undercover ATF informant. (Mack had also come to Montana to give a county-sanctioned training to the local sheriff’s department, but it got cancelled at the last minute due to staffing problems, according to the Daily Inter Lake.)

Or consider KrisAnne Hall, a former Florida assistant state prosecutor who was part of the “Stop the Steal” movement leading up to the January 6 insurrection. Hall has appeared at a League of the South event and teaches that the 14th, 15th, and 19th Amendments—the core of virtually all civil rights laws in the US—were an “unlawful expansion of federal power.” Her connection with Mack? She’s taught classes on such subjects as “The Importance of the American Sheriff” at at least three of Mack’s Texas law enforcement trainings this year.

Mack also spent much of this summer appearing on the cross-country “Arise USA!” tour that was slated to span 111 days and 87 events, peddling a host of conspiracy theories about COVID and vaccines and the results of the 2020 presidential election. It was organized by former CIA agent Robert David Steele, an outspoken anti-Semite and Holocaust denier who once told an Iranian newspaper that the United States “must eradicate the Zionist pest from our homeland.” The tour made it only to stop 81 in Jupiter, Florida, where Steele was hospitalized with the coronavirus. He died on August 28.

“These are people who would completely overthrow the entire civil rights framework of the United States,” says Chuck Tanner, a researcher at the Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights (IREHR), a Seattle-based nonprofit that tracks white supremacist groups. “It’s a radical assault on anything resembling democracy. And when the Texas commission signs off on that, it’s appalling. Any law enforcement with any integrity should not be anywhere near Richard Mack.”

Michael German, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice and a former FBI agent who went undercover to investigate neo-Nazi and militia groups in the 1990s, agrees. “The training you’re talking about [with Mack] isn’t happening in a vacuum,” he says. “We’ve seen more than a few cases of police officers joining actual militant groups, beyond the constitutional sheriffs. For the most part the FBI has no strategy to address it.”

Indeed, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform held a hearing on extremists’ infiltration of law enforcement in September 2020, but the FBI refused to participate. After the assault on the US Capitol on January 6, the committee sent a letter asking the FBI again for a briefing. “The shocking participation of law enforcement personnel in the January 6 domestic terrorist attack against Congress and our Capitol Police means that the Bureau must level with the American public about the steps it is taking to combat white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement agencies,” subcommittee chairman Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) wrote. A committee spokesperson says the FBI did provide the briefing and that the committee’s investigation is ongoing.

In response to criticism that the agency failed to see the January 6 insurrection coming, or the prominent role of law enforcement in the riot, FBI officials have told Congress that it doesn’t have the authority to monitor the social media accounts of every white nationalist or militia member. It’s true that the FBI is constrained by privacy laws and First Amendment concerns when it comes to monitoring social media accounts. Even so, you don’t have to be in a secret Telegram channel to see what’s going on with Mack’s work targeting law enforcement. It’s taking place in plain sight; now with the official approval of one of the nation’s largest states.

In July, IREHR complained to the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement about its decision to sanction Mack’s trainings. “CSPOA is currently co-sponsoring a nationwide tour with an antisemitic QAnon conspiracist,” wrote IREHR executive director Devin Burghart in an email raising several concerns about TCOLE’s support for the training. “Robert David Steele is a prolific purveyor of anti-Semitism who spews conspiracy theories about ‘satanic Zionists’ engaged in a global plot against white people.”

In response, the agency sent field agents to attend two of the trainings in Texas in July. Gretchen Grigsby, an agency spokeswoman, sent an email to IREHR stating that the agents “reported no discussion or delivered material that would be reason to deny continuing education credit to any licensed attendees.” When I ask TCOLE for comment on the trainings, Grigsby sends me a virtually identical email, explaining that just because TCOLE approves a group to provide continuing education credit doesn’t mean that the agency has endorsed the training or is involved in any way.

“The Texas Commission on Law Enforcement (TCOLE) places a great deal of trust in, and responsibility on, our contracted training providers who conduct, sponsor, or host courses,” she writes. “Unless the course is implemented by an act of the Texas Legislature, TCOLE does not conduct prior review or approval of training materials.”

If there was any doubt that the state has endorsed Mack’s trainings, though, on October 23rd, the top law enforcement for the entire state of Texas, Attorney General Ken Paxton, addressed the CSPOA conference in Mesquite, Texas. “It’s legitimate law enforcement training,” Mack insists when I ask him about the Texas endorsement. “We are the only ones who teach the oath of office.”

The ADL’s Pitcavage thinks that some of the concerns about extremists’ infiltration of law enforcement has been a bit overblown by liberals. “By and large, one cannot come up with a lot of examples of that,” he says. “But the CSPOA is the huge exception.” Mack’s group is not just recruiting retired or former officers, he says, but recruiting law enforcement executives—people at the top like Paxton—who are joining his group and speaking at his conferences. “What extremists crave is recognition, official recognition,” says Pitcavage. “When [Mack] can get official law enforcement bodies to get trainings, it allows him entrée into more spaces and places and allows him to promote his views about government.” States like Texas and Montana, Pitcavage says, “have officially approved what is essentially anti-government propaganda being delivered to law enforcement in their states.”

After Peroutka wraps up, I go outside to sit with Mack, where stink bugs fall on us as we chat under the trees. A fifth-generation Arizona Mormon, he has had an eclectic career. He has run unsuccessfully for Congress three times, and once for the Provo City Council. He abandoned his 2004 race for Utah governor to appear on Showtime’s reality TV show American Candidate, in which he participated in a fake presidential election. He has been a flack for the Gun Owners of America, a Second Amendment group more extreme than the NRA, and even sold cars. But he hasn’t actually been a sheriff since 1997.

He got his start in law enforcement in the 1970s, after serving an LDS mission in Guatemala and El Salvador. While he finished his degree in Latin American studies at Brigham Young University, he worked as a part-time “meter-maid” in the Provo, Utah, police department, doling out parking tickets. Mack’s father had been an FBI agent in Arizona for 25 years, and young Richard had hoped to follow in his footsteps but didn’t make the cut. An avid athlete, he liked the Provo police department’s softball team and ended up spending 11 years there as a full-time cop, even doing undercover drug busts—experience that taught him to loathe the “war on drugs.”

He told me that, like his father, he had once been a law-and-order sort of man, with deep respect for the government. But things started to take a deeper turn, two years after his father left the FBI, when the IRS audited him over $6,000 (which Mack says his father didn’t owe). “It took a huge chunk of his trust in the government he devoted 30 years of his life to,” Mack had told the Maryland audience.

The IRS audit clearly left a mark, but Mack’s “conversion to constitutionalism” really came from W. Cleon Skousen. A raging anti-Communist and John Bircher, Skousen had served as the Salt Lake City chief of police from 1956 to 1960 and had worked at the FBI with Mack’s father. One day, Mack saw a flyer at the police department advertising Skousen’s two-day training on “Constitutional Studies for Law Enforcement Officers.” Mack attended and was hooked. After 11 years in Provo, Mack went back home to Graham County, Arizona, and ran for sheriff in 1988. He won and served for the next eight years.

The Supreme Court case may have endeared him to Second Amendment enthusiasts, but it didn’t help much with the voters back at home. He lost his race for a third term as Graham County sheriff in 1996, and he hasn’t been in law enforcement since. Instead, he became a fixture of the then-burgeoning militia movement, periodically running for office. Later, he joined the tea party circuit that kicked off in 2009 after the election of President Barack Obama, speaking at more than 120 grassroots events.

Riding the tea party wave, Mack became an outspoken opponent of Obamacare, a position that came back to bite him in 2015 when he had a heart attack. Uninsured, he had to start a GoFundMe to pay his medical bills. To secure health insurance, he eventually took a job teaching history at an Arizona charter school founded by a Skousen acolyte—one indication that he’s never gotten rich off his activism. In his 2012 race for Congress in Texas, Mack faced questions about the 2004 foreclosure on his Utah house, as well as his 2005 bankruptcy filing. He told a San Antonio newspaper that those struggles simply proved how much he understood ordinary Americans.

But since the pandemic started, business has been booming. He had to quit his teaching job in November because of the renewed demand for his public appearances.

Even so, he says he does a lot of his events for free, and he tries to keep ticket costs under $100, mostly to cover food at the trainings. CSPOA is not a nonprofit. Initially, it got some money from the John Birch Society and Gun Owners of America but now Mack says it’s funded mainly by membership dues from people who join his “posse,” fees from his public speaking, and the occasional surprise donation from a fan. His recent tour in Texas, which involved several law enforcement trainings, was underwritten by wealthy businessman Gary Heavin, the founder of the defunct Curves fitness chain, who was also a speaker and is reported to have contributed to the Oath Keepers. Mack says he’s stopped bothering to ask the NRA to sponsor tables at his conferences because it has never given CSPOA a dime.

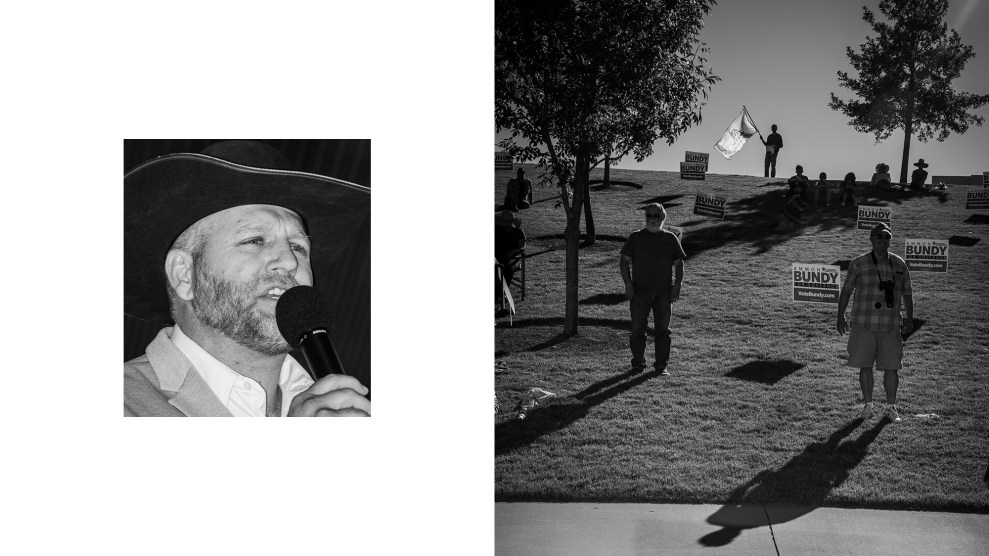

Mack has earned a loyal following in the West among Sagebrush Rebellion types who oppose federal control of public lands and believe they should be turned over to the states—a view Mack supports. He’s an old associate of another famous Western anti-government Mormon and Skousen devotee, Cliven Bundy. When Bundy made national news in 2014 for orchestrating an armed standoff with the Bureau of Land Management, Mack famously told Fox News that he had strategized with supporters to “put all the women up at the front.” He said, “If they are going to start shooting, it’s going to be women that are going to be televised all across the world getting shot by these rogue federal officers.”

In 2016, Mack was in Burns, Oregon, for a rally supporting ranchers Dwight and Steven Hammond when Cliven’s son Ammon led an armed takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge to protest the ranchers’ incarceration on arson charges. Mack claims he was unaware of the takeover plans; he never set foot in the refuge. He later testified in Bundy’s trial that he’d urged the occupiers to leave the refuge before someone got killed. (They didn’t and someone did.) The Bundys were arrested and charged with a variety of federal offenses for both the Oregon and Nevada standoffs, none of which resulted in a conviction, but Mack escaped unscathed. He credits 22 years in law enforcement for his survival instinct.

That instinct also kept him from going to DC on January 6. He’d had many invitations to attend, but says, “I just saw that it was too much emotion coming from Trump supporters and so many of ‘em thought he was going to give a huge announcement that he was going to stay in office. I thought that was stupid. I told people not to go. Our official stand was stay home.”

Under the trees in Maryland, Mack shows me a photo of his longest golf drive on a beat-up iPhone and tells me about playing basketball with one of his 15 grandchildren. With his easy laugh and Mormon earnestness, he reminds me a little of his friend Ammon Bundy, another charming Westerner considered a domestic terrorist. I ask Mack about this contradiction: If he’s not a racist or white nationalist or far-right extremist, why does he associate with so many people who are?

Mack does not think that proximity equals guilt. He insists that even the Southern Poverty Law Center has had to concede that he’s never made a racist comment. But what about his association with Peroutka, the former board member of the neo-confederate League of the South? “I’ve never heard of the League of the South,” he tells me. As for Peroutka, “I’ve never heard him say anything racist.”

And what of the recently deceased anti-Semite Robert David Steele? Mack says that Steele had said so many crazy things—including about Mormons, which Mack found offensive—he couldn’t imagine anyone would take him seriously. Still, during the “Arise USA” tour, Steele’s erratic behavior and anti-Mormon bigotry had made Mack so uncomfortable he had decided to step back. Then Steele got sick. With a smile, Mack says he preferred to spend his time palling around with “that racist” Kevin Jenkins, a Black anti-vaccine activist who was also featured on the tour.

Even so, it’s probably no coincidence that his Maryland event took place on the Eastern Shore, a part of the “Free State” often referred to as the “Mississippi of Maryland” because of its legacy of slavery and lynchings. During the lunch break, a man at my table gives me an unprompted tutorial on the “war between the states,” and insists that the Emancipation Proclamation was unnecessary because the Civil War wasn’t about slavery. “It was about tyranny,” St. Mary’s County resident John Lee tells me. When I ask where he learned this particular view of American history, he replies that it was from another one of Peroutka’s classes on the Constitution. “We’re being taught [the Civil War] was based in race,” he insists. “It was not based in race.”

After an hour chatting affably with Mack under the bright October sun, I realize that many of Mack’s contradictions stem from the fact that he is an equal opportunity evangelizer—or publicity hound, depending on your perspective. He will talk to or appear with virtually anyone—including Mother Jones, an outlet he makes clear he doesn’t think much of. He says he’d talk to the Anti-Defamation League or the Southern Poverty Law Center or the NAACP if they asked. They don’t, of course, but the white supremacists occasionally do, and he generally doesn’t seem to turn them down.

“I have assailed racism my entire life, I assail it in all of my speeches,” he tells me later, when I ask him to respond to the charge from groups like the ADL that he fraternizes with white supremacists. He complains that his critics never seemed to have a problem with Democrats like Joe Biden associating with the late Democratic senator from West Virginia, Robert Byrd, who had been a “grand poobah” of the Ku Klux Klan. “I’m the racist? Yeah, right. There’s a different standard for Washington politicians,” he says. “You’ve never seen me rubbing elbows with Robert Byrd.” (Byrd died in 2010.)

Eventually, we flee the stinkbugs as Mack is summoned back to the podium for an afternoon question and answer session. By then, he’s been at FoamWorks for hours, and seems in no hurry to leave. He fields questions about whether citizens should form a posse to take the law into their own hands—he hedges on that one—or how to make sure that a sheriff is really “constitutional.” He poses for selfies and sells more books before finally signing off. “God bless you,” he tells his fans, “as you defend liberty for my 15 grandchildren.”

This article has been updated with the following corrections: Sheriff Richard Mack disputes the characterization in an earlier version of this article of his role in the Oath Keepers’ founding; he is a longtime Oath Keepers board member. The same version of this article misidentified the federal agency whose informant purchased sawed-off shotguns from white nationalist Randy Weaver, Mack’s associate; it was the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Finally, it has been revised to more accurately detail limitations on the FBI’s authority to monitor individual social media accounts.

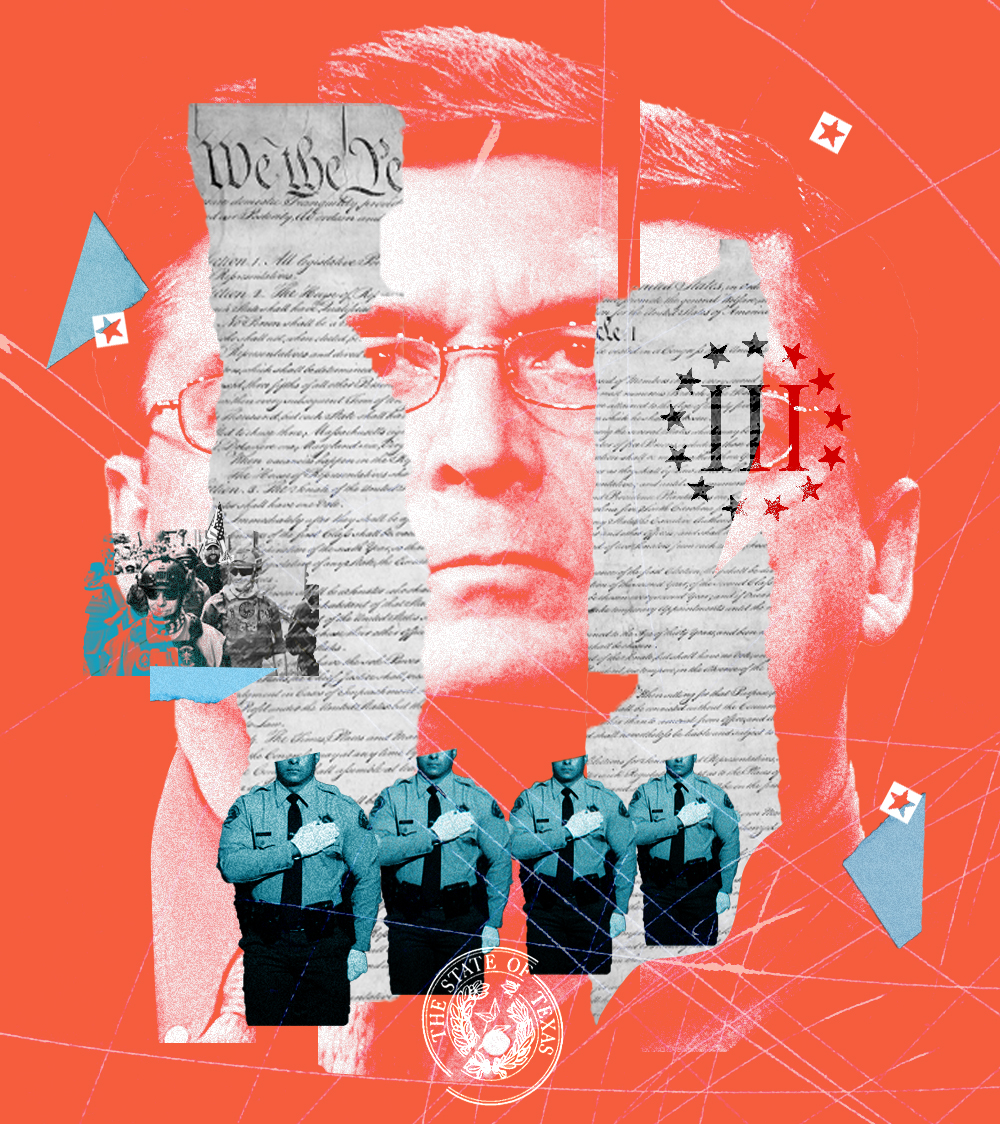

Top image: Mother Jones illustration; Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic, Inc/Getty; VCG Wilson/Corbis/Getty; Stephanie Keith/Getty; Mario Tama/Getty