Robin Rayne/ Zuma

This article was originally published by Public Health Watch, a nonprofit investigative news outlet.

In January 2001, relief was in sight for hundreds of thousands of American workers with pinched nerves, herniated discs, carpal tunnel syndrome, and other conditions so painful they couldn’t do their jobs.

A federal rule addressing an explosion of workplace ergonomic injuries had taken effect. It required more than 6 million employers to identify jobs that subjected workers to “repetition, awkward posture, force, vibration and contact stress,” and, if necessary, alter those jobs to eliminate or reduce the risk of injury.

The rule survived all of six weeks before Congress smothered it.

Twenty years later, while the overall number of reported cases has fallen, musculoskeletal disorders continue to torment workers in warehouses and health care facilities, and on construction sites. On top of that, a new public health scourge has taken root: the overuse of prescription opioids for chronic pain, often caused by injuries on the job.

The demise of the ergonomics rule didn’t cause the opioid epidemic, which took nearly 70,000 lives in the United States last year. The blame for that lies mainly with drug manufacturers that peddled addictive painkillers and doctors who freely prescribed the pills.

But had the rule been allowed to stand, many workers would not have suffered injuries that make drugs like oxycodone so appealing, researchers and former government officials say. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in July that fatal unintentional overdoses in the workplace from alcohol and drugs, including opioids, increased 329 percent from 2011 to 2019, from 73 cases to 313. A survey commissioned by the National Safety Council in 2017 found that 70 percent of responding employers said they had been impacted by prescription drug misuse in the form of absenteeism, impaired job performance, injuries, or other workplace problems.

Dr. Michael Silverstein, director of policy for the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration in the early 1990s and later head of Washington State’s division of occupational safety and health, said Congress’ dismantling of the 2001 rule is partly to blame. “There’s little doubt that our failure to take preventive steps on ergonomic injuries has resulted in a secondary effect of opioid dependence and opioid-related deaths,” he said.

Research supports Silverstein’s position. A University of Utah study from 2013, for example, found that 57 percent of people who died from an opioid-related overdose had suffered at least one work injury; 13 percent of overdose deaths had been preceded by a work injury within the previous three years.

Legislation could help fix the problem but seems unlikely given the gridlock in Washington.

“When we were working on the rule (at OSHA), the question was, ‘What’s going to happen if we don’t regulate?’” Silverstein said. “What we didn’t anticipate is the way that a lot of companies have rushed in with opioids as a way to keep workers on the job. The consequences have been devastating and so unanticipated.”

On November 14, 2000, as the nation fixated on a disputed presidential election, OSHA moved to address the nearly 600,000 musculoskeletal disorders a year that resulted in lost workdays.

At hearings earlier in the year, OSHA had taken testimony from workers like Alberto Turienzo, who had been fired by Goya Foods after complaining about practices in the company’s Miami warehouse. “I know many colleagues, co-workers, who’ve been injured, especially in the arms, the back and the shoulders for carrying and pushing excessively heavy weights,” including 110-pound sacks of rice, Turienzo said.

Labor unions had petitioned the agency to do something about such conditions in 1991, and now, in the waning days of the Clinton administration, it had. Although the number of musculoskeletal disorders reported to the Bureau of Labor Statistics had fallen by 20 percent since 1992, OSHA said in the preamble to the rule, “These disorders have been the largest single job-related injury and illness problem in the United States for the last decade, consistently accounting for 34% of all reported injuries and illnesses.”

The ergonomics standard was highly prescriptive, setting an “action trigger” that would determine whether an employer had to establish an ergonomics program for a particular job. Such a program would have to include “hazard information and reporting, management leadership and employee participation, job hazard analysis and control, training, [musculoskeletal disorder] management, and program evaluation.”

This did not go over well with industry groups. A vice president with the US Chamber of Commerce called the standard “unconstitutionally vague” and said there was “no scientific basis” for it. There were predictions of economic doom precipitated by government meddling in work processes. OSHA estimated businesses would have to spend a collective $4.5 billion to comply with the rule but ultimately would save twice that amount in costs related to disabling injuries.

The US Supreme Court ended a recount of the presidential vote in Florida on December 12, 2000, handing the White House to George W. Bush. The ergonomics standard took effect as scheduled on January 16, 2001. Not quite two months later, it was rescinded under the Congressional Review Act, which gives lawmakers the ability to nullify rules within 60 legislative working days of their transmittal to Congress.

The vote was largely along party lines. Republicans opposed the regulation, calling it “intrusive” and “job-killing,” and Bush signed the repeal into law on March 20. It was a crushing defeat for worker advocates and OSHA, which was barred by the act from issuing a “substantially similar” rule at a later time.

As ergonomic injuries were sidelining workers in the late 1990s, another phenomenon—escalating abuse of pain-blocking opioids—was coming into focus. In 1999, there were fewer than 10,000 deaths in the U.S. from opioid overdoses. Two decades later, there were 50,000. The COVID-19 pandemic, which in many cases led to extreme isolation and limited access to treatment, only made things worse.

Workers were especially susceptible to the painkillers during the pandemic, as they faced stressors such as “job uncertainty, fear of job loss and reduction in income,” the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health noted in a recent blog post. In another post, NIOSH reported that a third of construction workers have at least one musculoskeletal disorder and prescription opioid use is three times higher for this group than it is for workers who are unhurt.

“It’s just an outrage that it’s not being addressed,” said Jonathan Rosen, an industrial hygiene consultant to the National Clearinghouse for Worker Safety and Health Training. “When a worker gets injured and there’s pain, they’re given prescriptions. Insurance won’t cover alternative treatments but will cover opioids.”

In a recent journal article, Rosen and Aurora B. Le of the University of Michigan School of Public Health argued that zero-tolerance drug policies in U.S. workplaces had created a “culture of underreporting” of opioid misuse. “Worksite programs that are punitive and stigmatizing do not foster a culture where workers are comfortable coming forward for help or care,” they wrote.

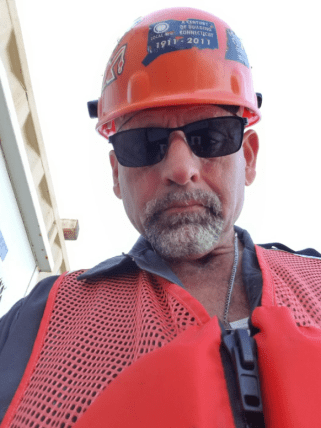

Dino Carbone, a crane operator from Milford, Connecticut, didn’t get hurt on the job but did become addicted to opioids, an affliction that affected his ability to work and nearly destroyed him personally. Carbone was prescribed Roxicodone for his aching shoulders—damaged by competitive powerlifting—in 2003. At first, he said, “I seemed to be managing it well, taking my prescribed dose. After a while, the prescribed dose doesn’t work because your body builds up a tolerance to it.”

Carbone kept taking more pills and by 2013 “was not able to hold down my job correctly. I would be out of meds and feel like garbage when I came to work, or would be late for work.” He’d doze off in the cab of his crane and, when confronted by a boss, blame sleep apnea. He had no serious accidents but couldn’t hold a job.

Carbone was saved by a member-assistance program begun in 2010 by the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 478, to which he belonged. The local’s health and safety director, Kyle Zimmer, had helped start the program after an explosion at a power plant under construction in Middletown, Connecticut, killed five union workers and a manager, and injured 60.

Some Local 478 members developed post-traumatic stress disorder after the blast, Zimmer said. “They were trying to access help through our benefits system and were getting nowhere, or were getting the wrong kind of help,” he said. The local hired two counselors and began holding weekly “peer recovery” meetings—to which members, their families and non-union construction workers were invited. The program claims an 80-percent success rate.

Zimmer convinced Carbone his career would be over if he didn’t get additional help. Carbone agreed to enter a rehabilitation center in Pennsylvania, where he spent 33 days, slept only a few hours a night, and endured the agony of withdrawal. He felt terrible for six months after he was discharged. “It took a long time for that crap to get out of my system,” he said. But eventually, he started sleeping, lost weight, and regained his self-esteem.

“I was able to get better jobs,” Carbone said. “Now I’m dependable. I show up an hour early every day as opposed to an hour late.”

In the absence of a federal ergonomics standard, some states have acted on their own. On Sept. 22, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law a bill targeting Amazon and other warehousing companies that use algorithms to measure productivity. The law forbids employers from penalizing workers for complying with health and safety rules, including those requiring restroom breaks.

Washington State has its own occupational health and safety program and, like federal OSHA, had an ergonomics rule repealed, in this case by voters. Nonetheless, it made headway against opioids by establishing dosing guidelines.

“Prescribing has gone down,” said Dr. Gary Franklin, medical director of the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries. “We’ve really cut down on deaths in the workers’ comp system, cut down on the number of workers getting opioids.”

Legislators in New York changed the state’s insurance law to reduce delays and costs for people needing immediate treatment. Employers are offered tax credits of up to $2,000 if they hire and retain for at least 500 hours “eligible individuals in recovery from a substance use disorder in part-time and full-time positions.”

Nationally, the number of lost-time ergonomic injuries reported to the government has been falling. There were 266,530 in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, down from 311,840 in 2011. The injury rate dropped as well.

Some companies have tackled the problem without waiting for the government to tell them what to do. But Silverstein cautioned that ergonomic injuries are routinely underreported. A 2001 OSHA requirement instructing employers to record musculoskeletal disorders in a specific column on illness and injury logs never fully took effect before it was abandoned by the Bush administration. Data from these logs goes into the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ annual survey of occupational injuries and illnesses. The elimination of the requirement gave employers a variety of ways to mischaracterize such disorders on the logs and escape BLS counting, Silverstein said.

A 2008 report by the Democratic staff of the House Education and Labor Committee cited research estimating that up to 69 percent of injuries and illnesses didn’t make it into the BLS survey. Employers have “strong incentives to underreport,” the staff found. “Businesses with fewer injuries and illnesses are less likely to be inspected by OSHA; they have lower workers’ compensation insurance premiums, and they have a better chance of winning government contracts and bonuses.”

In 2014, after surveying workers at a Maryland poultry-processing plant plagued by ergonomic injuries, NIOSH identified 20 injuries or illnesses that should have been recorded on OSHA logs. Only one was.

OSHA’s ability to float another ergonomics rule appears to be stymied by the Congressional Review Act. Legislation authorizing a new rule would seem to be the only option, and the prospect of that seems dim given expected opposition from Republicans and businesses.

Asked what OSHA could do about musculoskeletal injuries, an agency spokeswoman wrote in an email that employers are obliged, under the general duty clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, “to keep their workplaces free from recognized serious hazards. In the workplace, the number and severity of musculoskeletal disorders resulting from physical overexertion, and their associated costs, can be substantially reduced by applying ergonomic principles.”

Eric Frumin, health and safety director for the Strategic Organizing Center, a coalition of four unions, said that “reliance on the general duty clause to prevent back pain and other (musculoskeletal) injuries has been a failure – with only a handful of violations issued in the last two decades.” Executives at companies such as Amazon know this, he said, and “have designed workplaces with ever-greater risks to workers.” Amazon representatives did not respond to requests for comment.

Frumin said corporate opposition to the OSHA ergonomics standard was never primarily about cost. “It’s about control and power,” he said.

The rule would have given tens of millions of non-union workers a way to push back against abusive bosses, Frumin said.

“Workers have no control,” he said, “and they get hurt and their lives are ruined.”

Jim Morris is executive director and editor-in-chief of Public Health Watch, a nonprofit investigative news organization.