Bob Daemmrich/ZUMA Press Wire

When Beto O’Rourke, then a Democratic congressman from El Paso, announced in the spring of 2017 that he would run against Sen. Ted Cruz in the next year’s midterms, he was treated as a sunny curiosity. National Democrats, wary of being sucked into a resource-intensive longshot project, were focused elsewhere. Texas Republicans, confident of their seemingly impervious standing in the state, considered it a “suicide mission.” Those low expectations were a blessing—spared from a contested primary and free to tour the state as he pleased, he nearly pulled off one of the biggest political upsets in a generation. He raised huge sums of money, shattered turnout models, and helped to rebuild a party that had been neglected for years. And it wasn’t just O’Rourke—other Democrats, running similarly darkhorse challenges in races from county judge to Congress, broke through. For the first time in ages, Democrats in Texas seemed to be ascendant.

The ensuing years have not gone as well for either O’Rourke or his state party. In the wake of the midterms, after talking seriously about taking back control of the state House of Representatives, Texas Democrats only flipped one seat—and lost another—in 2020, as President Donald Trump won the state easily. O’Rourke, for his part, decided to run for president rather than challenge another Texas senator, John Cornyn. He dropped out before the first primary votes were even cast.

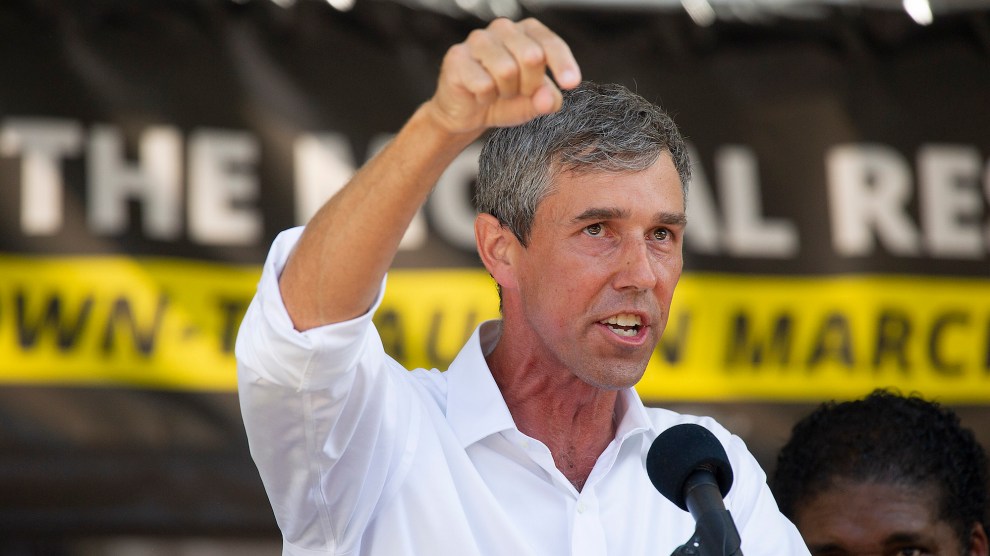

But now, O’Rourke is back again—and he’s hoping 2022 will look a lot more like 2018 than last year’s election. In a video released Monday, O’Rourke launched his campaign for governor against two-term Republican Gov. Greg Abbott.

I’m running for governor.

Together, we can push past the small and divisive politics that we see in Texas today — and get back to the big, bold vision that used to define Texas. A Texas big enough for all of us.

Join us: https://t.co/eMY5wwf6an pic.twitter.com/yrG1WOkpqk

— Beto O'Rourke (@BetoORourke) November 15, 2021

Abbott is vulnerable to a challenge, at least in theory, on everything from his handling of the pandemic to the blackouts to the law he recently signed banning abortions before many women even know they’re pregnant. Rather than manage the state through the crises of the last few years, he has preferred to invent new ones, while performing a Trump-lite role for the benefit of conservative TV audiences. A government that can’t even keep the lights on in winter is considering spending tens of millions of dollars to build its own border wall. After a racist massacre at an El Paso Walmart, Abbott said “mistakes were made” in the language his campaign had sometimes used to talk about immigration; two years later, he still uses the same talking points as the gunman. Abbott has failed massively in ways that have cost his constituents their lives. But in raw political terms, well, he also has $55 million in campaign funds and the national political winds at his back.

Barring a major change in national attitudes, the 2022 election is shaping up to be somewhere between very and extremely bad for Democrats. And in Texas, the usual problem of a midterm election in a Republican-leaning state with an unpopular president and an ongoing attempt to selectively restrict voting access will be compounded by the rollout of a new state and federal district map, aimed at rolling back recent Democratic gains and solidifying Republican control for the decade to come. And O’Rourke’s own political identity has evolved too, from the energetic live-streaming El Paso outsider, into a more conventional progressive Democrat. (He even got a job in Austin.) His presidential campaign didn’t yield any delegates, but it did produce moments in which O’Rourke—transformed into a gun-control activist in the aftermath of the El Paso attack—promised, “Hell yes, we’re going to take your AR-15.”

On Monday, while O’Rourke was announcing his next move, Abbott was in Rio Grande City, where state Rep. Ryan Guillen, a 10-term Democrat, announced he was joining the majority party. Guillen was the most conservative Democrat in the chamber, but that is hardly consolation—it is the latest indication that South Texas might be shifting away from the heavily Democratic stronghold it’s been for a century.

Running against Abbott in 2022 will make the race against Cruz—a notoriously disliked senator coming off his own failed presidential campaign—look easy. But O’Rourke, whatever the strategic wisdom of his recent political decisions, has proved his willingness to put in the work for his party and his causes. While his name wasn’t on the ballot in 2020, he threw himself into the task of registering and turning out voters in his state. It was a real political infrastructure he was building—Democrats had many problems in Texas that year, but turnout wasn’t really one of them—and one he was equally comfortable deploying for non-partisan uses. When the state’s power grid failed in February, a foreseeable crisis rooted in the state government’s history of deregulation, Cruz fled to Cancun; O’Rourke set up phone banks for Texans to check in on seniors and make sure they were okay.

In an environment like this, Democrats couldn’t really afford to let Abbott, with everything he’s done and undone in office, go unchallenged. (What would even be the point of a political movement that did?) They couldn’t, in other words, afford another Lupe Valdez—the hapless and underfunded Dallas County sheriff who entered the race late and got steamrolled by Abbott four years ago. They needed a big-time candidate at the top of the ticket, someone who’s visible and serious and relentless and can raise tons of money—someone everyone knows. Beto’s no Matthew McConaughey, perhaps. But the only situation that might be tougher than the one O’Rourke is getting into now is the situation Texas Democrats would have found themselves in without him.