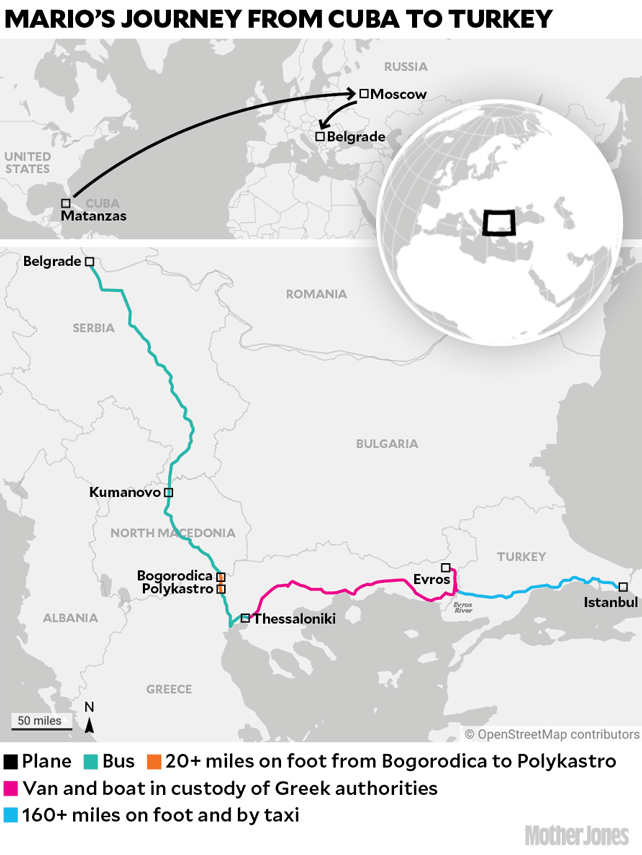

In October, a 38-year-old doctor who had never before set foot in Europe sat on a bus with his two friends outside the small town of Polykastro, Greece. Relief was beginning to set in. The doctor, who asked that I refer to him by a pseudonym, Mario, had taken an expensive and taxing trip from Russia to Serbia, and from there traveled roughly 260 miles overland into Greece. There, he could apply for asylum in the European Union, which was the reason he left his home country in the first place. More than a million asylum seekers had arrived in Greece since 2015, so in this way his journey was unremarkable. But Mario was part of one of the newest refugee exoduses into Europe: from Cuba, an island roughly 6,000 miles away.

Europe had long loomed large for Mario as a place that not only offered a sustainable and dignified life, but also one that fundamentally respected human rights. But just outside Polykastro on the road to Thessaloniki, his bus pulled over and two plainclothes police officers boarded, demanding papers of anyone who didn’t look Greek. Mario and his two travel companions didn’t have any. The police escorted them off the bus along with five others: a man from Pakistan, and, as it happened, a family of four from Cuba. All of them told the police they wanted to apply for asylum in Greece. The police took away their belongings and loaded them into a white van.

“Do not worry,” Mario recalls them saying, “nothing is going to happen. Everything is okay.”

From there, the group was taken to a detention center, where they stayed overnight in squalid, foul-smelling cells. Late at night, another Cuban family was brought in: a mother, a father, and their 3-year-old. The next morning, 30 detainees were loaded into a van and driven four hours to the region of Evros—a solemn, green stretch of land abutting Turkey where trucks packed with uniformed army officers roam. The police brought them to a military base, stripped them, and beat them with blocks of wood and plastic batons. Then the police moved them to a remote, wooded border zone, where officers forced them to take off their shoes and walk, in silence, through the forest until they reached the Evros River.

When they reached the riverbank, Mario saw a uniformed officer striking a young man who Mario suspected was Afghan in the face with a length of barbed wire and repeatedly plunging his head into the water. The young man begged for mercy and not to be sent back across the border. Mario was sure they were all being taken to their execution—their loved ones wouldn’t know how or where they died. Instead, they were loaded onto inflatable boats, which the officers steered across the river. On the other side, they were told to get off. Mario disembarked in Turkey and ran for his life.

Just like that, Mario became one of a growing migration of Cubans seeking asylum in Europe via Moscow—and one of the estimated thousands of asylum seekers illegally expelled from Greece since 2020.

Mario was an anesthesiologist in Havana, struggling to make ends meet. He earned roughly $160 a month, and the pressures of COVID-19 had taken a real toll on him. He was expected to work alternating 24-hour shifts, and his hospital lacked both necessary equipment and medicine to care for patients.

But the problem of scarcity stretched far beyond his hospital. Due to a combination of the pandemic and US sanctions, the Cuban economy took an 11 percent hit in 2020, leading to shortages not just in medicine but also in food and basic household items. The challenges have continued into 2021. Even people with middle-class jobs, like Mario, have struggled to afford food—or, when they had the money, to find anything on the sparse grocery store shelves. In July, widespread protests erupted throughout the country; authorities met them with tear gas and accusations that the protesters were anti-revolutionary plants organized by the United States.

The flailing economy and widespread government repression have pushed more and more people to leave the country. Historically, Cubans have migrated to the US due to geographic proximity and permissive anti-Communist asylum policies. Approximately 1.4 million left in the wake of Fidel Castro’s 1959 coup, and thanks to the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act—which rendered any Cuban who reached US soil eligible to apply for a green card—immigrants from Cuba constituted the fifth-largest green card acceptance rate as recently as 2015.

But the 2019 Trump-era policy commonly known as Remain in Mexico effectively put an end to the special treatment of Cubans at the border. Instead of being admitted to the United States to pursue their asylum claims, all asylum seekers, regardless of nationality, were forced to wait in Mexico while their cases worked their way through immigration court. Roughly 11,000 Cubans have initiated US asylum applications under Remain in Mexico—the largest number of applicants after Honduras and Guatemala, which both had record-high numbers of asylum seekers in recent years. (And though the Biden administration suspended the program earlier this year, Remain in Mexico was reinstated just last week following a court order.)

It is unknown how many more Cubans were kept from filing asylum cases at all since the start of the pandemic. In March 2020, Trump invoked a decades-old public health statute known as Title 42 to effectively shut down the border. Since it was enacted, more than 1.2 million people have been expelled to either Mexico or their home country. Despite the Biden administration’s vows to reverse Trump-era immigration policies, the statute remains in place.

As the pandemic continued to rage in Cuba and the food shortages showed no end in sight, Mario started to feel like he had no choice but to leave Cuba. The problem, amid all this tumult at the US-Mexico border, was figuring out where to go. In recent years, Cubans heading to the US had often first flown to Nicaragua or elsewhere in the Americas before traveling overland through Mexico, but by the time his situation had reached a breaking point this fall, the only flights leaving Cuba that didn’t require a prearranged visa were to Russia, where Cubans could enter as tourists. While he had no interest in living in Russia, it was close to the EU—a place he very much wanted to go.

The number of Cubans entering Europe via Russia seems to be growing. In 2020, 2,040 Cubans sought asylum in the EU, compared with 610 in 2015. In October, a group of nearly 100 Cubans were arrested on the tiny Greek island of Zakynthos, boarding a flight to Italy; according to an English-language news site called the Greek Reporter, they’d heard from other Cubans who’d taken the same trip that flights from Zakynthos had lax visa enforcement. “This is a totally new route,” explained Natalie Gruber of Josoor, an international watchdog group that monitors border activity and human rights on the Turkish side of the border.

Mario got in touch with others who had taken this journey, and began to make plans. He owned a small apartment in Cuba and sold it for approximately $10,000, which he’d use to pay for his trip and restart his life in Europe. What Mario didn’t know was that the European Union had been host to an unprecedented number of refugee arrivals since 2015—and that, in recent years, border countries like Greece had been carrying out covert expulsion operations designed to both get rid of asylum seekers and send the message that Europe is closed.

Under international law, any expulsion of asylum seeker before they have a chance to apply for protection, a practice known as refoulement, is illegal. And yet such practices are widespread throughout Europe—from Greece to Croatia to Poland—and only getting worse in their violence and scale.

While credible accounts of these so-called pushbacks from Greece have been reported for years—particularly along the land border with Turkey where Mario was expelled—they seem to have become a matter of routine policy under the right-wing government that was voted into power in 2019, in part on a tough-on-migration platform. Expulsion reports have only spiked since February 2020, when Turkey announced it would no longer patrol its borders to keep migrants from crossing into Europe, as it had been obliged to do since signing a 2016 agreement known as the EU-Turkey deal. That month, refugees rushed the border between Turkey and Greece, prompting EU authorities to send additional militarized border units and presaging a similar situation that would arise along the Belarus-Poland border earlier this year.

In the meantime, reports of expulsions from Greece have soared. Unlike previous years, not only were refugees pushed back across the land border soon after crossing, but they were also plucked from deep inside the country and forced across the border, as Mario was. It was happening at sea, too: Coast Guard vessels were blocking boats and dragging them back into Turkish waters, and even finding asylum seekers who had landed on the islands and taking them back out to sea, to drift.

The exact numbers of these illegal expulsions are difficult to come by, because these are covert operations. But the numbers that are known are staggering. From March to December 2020, an NGO called Mare Liberum counted 321 pushback events at sea, involving an estimated 9,798 people. Meanwhile, the Border Violence Monitoring Network has amassed detailed testimonies of 150 pushback events by land and sea in Greece between March 2020 and December 2021, totaling roughly 9,700 people.

“These crimes committed by the authorities—nobody documents them,” explains Marie Read from Mare Liberum, which monitors human rights abuses and refugee arrivals on the Aegean Sea. “Obviously authorities aren’t going to do it. The only ones who do it are the ones on the ground, NGOs. If it’s not done, there’s no info about it. It’s as if it’s never happened.”

But again, Mario knew none of this. On September 25, he arrived at the airport in Matanzas, an hour and a half east of Havana, along with his close friend, passport in hand, ready to board his plane to Moscow. As is standard for doctors in Cuba, he’d had to secure special permission to leave the country, which by some miracle was granted. At the airport, the immigration officer asked him whether he planned to travel from Russia to another country.

“Of course not,” he told her, nervous she’d see through his lie. But, in another stroke of luck, she let him through. “They know,” he told me. “They know that people are going to Russia to go to Europe.” The vast majority of those on the plane, he said, were Cubans, save for some Russians in first class.

He arrived in Moscow, where he and his friend spent a month in a rented apartment. Using a Facebook group called “Cubans in Moscow,” he connected with others who had taken this journey. There were people who could help arrange the entire trip, but that cost roughly 5,000 euros per person—a price he and his friend couldn’t afford. So they opted to figure it out themselves.

They knew the most direct route was to get to Serbia, another country that didn’t require prearranged visas from Cubans, and from there head south through Macedonia and into Greece. They visited a travel agency and booked a plane ticket to Belgrade, but when they arrived at the airport, the ticketing agent wouldn’t let them on. The plane transferred in Athens, and they didn’t have a visa to the EU—so they wouldn’t be allowed to board. After that, they booked another, nonstop flight to Belgrade, but this time they were turned away at the airport for lacking a current-enough COVID test. They weren’t refunded for either flight. Finally, they were able to book a flight from St. Petersburg to Serbia, and boarded this time without problems.

Once they got off in Serbia, they met up with another friend taking the same journey and began looking for a bus to Skopje, North Macedonia. “We had no idea where to go, and we needed help,” Mario told me. Another Cuban had put them in touch with a Chilean man who had lived in the EU for a long time. For 500 euros each, he’d help them reach Greece. He instructed them to download an app called Life360, a location safety app that would allow him to see where they were at all times and direct them where to go.

He told them where to get the bus to Skopje. They boarded, but just a little ways down the road the driver stopped and asked them for another $100 each. “Everyone is trying to profit, all the time,” Mario told me. They had no choice but to pay.

The coyote instructed them to get off the bus at Kumanovo, a small town in Northern Macedonia. From there, they boarded another bus to the Princess Casino Gevgelija on the border with Greece, where the coyote led them via the app to a small hole in the fence where they could cross the slow-flowing Vardar River into Greece. They were in the EU.

Mario had hurt his knee, but they were instructed to walk 9 miles from the border to a town called Polykastro, which struck them as funny: They couldn’t seem to escape the Castros. In Polykastro, they boarded a bus to Thessaloniki, where they’d be able to apply for asylum. But just a few minutes after the bus left the station, they were stopped, and Mario’s forced expulsion to Turkey began.

Just as more Cubans are making their way to Europe via the new Moscow route, more are being illegally expelled by Greek authorities. Mario is part of a community of 34 Cubans in Istanbul, all of whom arrived in Greece only to be pushed back to Turkey—only they weren’t pushed “back” at all, since, unlike most pushback victims who start their journey to Greece from Turkey, the Cubans had never even set foot in Turkey to begin with.

For now, Mario lives in a small studio paid for by a local church, which he shares with four other Cubans who were forcibly expelled from Greece. He has no money and none of his identity documents, which were stolen by the Greek authorities. He fears the church’s charity will run out soon. Above all, he remains stunned by what happened to him.

“That this could happen in a democracy, and in Europe—I can’t believe it,” he told me. Almost as traumatizing as the journey itself, he says, is the disillusionment that such a thing could happen in plain sight, and that no one was there to fight his expulsion or protect him.

Mario wants to warn people before they leave Cuba, and that was one of the reasons he was eager to speak to me. He also took to the Cubans in Moscow Facebook group: “HELLO I AM SENDING A MESSAGE IN ALL CAPS TO THE CUBANS WHO ARE PLANNING TO REACH GREECE,” he wrote. He begged them all not to try it, as the Greek police were deporting Cubans with force, torturing people, taking their belongings and documents. “Please value your lives I am writing you with sincerity you do not want to go through the most unpleasant experience I’ve lived.”

Mario hopes everyone will read his post, and share it. This is perhaps the point of pushbacks: to make life so brutal for refugees that word gets back home, and people stop trying to come.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.