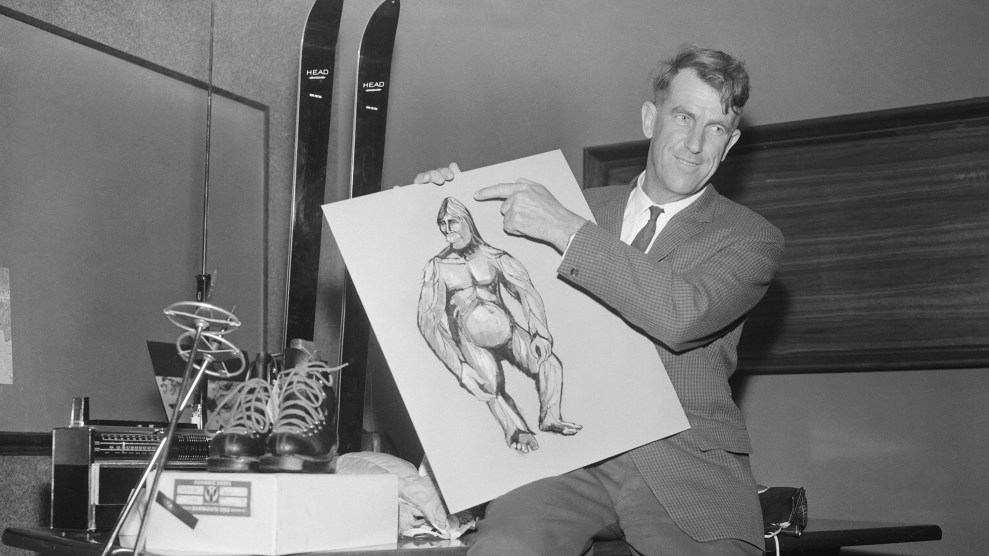

Famed mountaineer Edmund Hillary displays a yeti rendering at a 1960 news conference before departing for the Himalayas.Bettmann archive/Getty Images

This story was originally published by Atlas Obscura and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

September 9, 1960 — Kathmandu hums with the discordant music of drums and flutes. People disguised as dancing deities have traveled from all over Nepal to clap and sing their way through the streets as part of a festival honoring the Hindu god Indra, revered as the king of heaven. Amid the colorful melee winds 40-year-old Brit Desmond Doig, mountaineer, journalist, and photographer for National Geographic and Life magazine.

In the midst of the chaos, Doig spots a shaggy-haired wool and bamboo figure halfway between a man and an ape adorning the wall of a temple. “To the Nepali they are ‘Ban Manchhuru’,” Doig writes in the 1962 book High in the Thin Cold Air. “To our Sherpas and us… the figures represent the Abominable Snowman.”

Doig hadn’t traveled all the way to the Nepali capital to honor Indra. As part of the 1960-61 Silver Hut expedition led by Edmund Hillary, then the world’s most famous mountaineer, Doig had come in search of a creature that, like a god, occupied the rarified air between myth and reality. He had come in search of Nepal’s abominable snowman, also known as the yeti.

In the 1950s and early ‘60s, the Western world was in the grip of yeti mania. In 1951, the legendary mountaineer Eric Shipton had photographed what he believed to be yeti tracks in northeastern Nepal. The following year, Hillary himself encountered a scrap of skin covered in blue-black fur while climbing in the Cho Oyu region of the Himalayas and was told by his Sherpa porters that the hair belonged to a yeti.

Following two bloody World Wars and indeed, Hillary’s earlier exploits, the vast majority of the globe was now known to Western audiences. The sections of the map reading “Here be monsters” were growing fewer and fewer, yet the appetite for undiscovered lands and unseen monsters had never been stronger.

Belief in the yeti can be traced to pre-Buddhist religions, but widespread interest came about as Western mountaineers first began to climb the Himalayas and brought the local legends home with them. When the race to conquer Everest heated up in the 1950s, so too did the number of alleged yeti sightings. Western audiences were hooked, eager for news of this evolutionary hangover halfway between man and beast. Perhaps it was comforting to think that there were beings beyond comprehension surviving at the ends of the wilderness and that, crucially, there were still enough wild places left to hold them.

So popular was the yeti legend that British newspaper the Daily Mail launched its own expedition to Nepal in 1953. The trip cost the equivalent of $1.35 million in today’s money but ultimately failed to find any proof of the yeti. All of which simply meant that in 1960 yetis were still out there to be found.

“The yeti wasn’t considered mythical in the early ’60s,” explains Graham Hoyland, mountaineer and author of Yeti: An Abominable History. Hoyland points to the Nepali government’s official 1947 memo outlining the etiquette of a yeti hunt, republished by the American embassy in Kathmandu in 1959 and issued to Hillary’s party as “Regulations Covering Mountain Climbing Expeditions in Nepal Relating to Yeti.” It stipulates that the search for yetis required a permit and that a yeti could not be killed except in self-defense.

That Edmund Hillary might set off in search of the abominable snowman, then, was not the wild, conspiracy-theory-baiting story it would appear to be today. That he and Doig might actually encounter a wild yeti was considered a very real possibility.

It was in this spirit that the Hillary expedition set out into the Rolwaling Valley on the morning of September 10, 1960. The valley selected because Sherpas in the had reported yeti sightings in the area and because of its proximity to Mount Makalu, the world’s fifth highest mountain; the nine-month expedition would go on to study the effects of long-term exposure to high altitudes on human fitness after the search for the yeti was concluded.

Among those traveling on the dual-purpose expedition were Peter Mulgrew and Wally Romanes, who had accompanied Hillary on his 1955-58 expedition to Antarctica; American space physiologist Dr Tom Nevison and glaciologist Barry Bishop, both well suited to measuring the effects of long-term altitude exposure; and Marlin Perkins, director of the Lincoln Park Zoo, and Dr Larry Swan a self-described “Himalayanist,” whose expertise seemed ideal for a yeti hunt. In other words, this was a serious, well-funded and professional expedition, one backed by World Book Encyclopedia

The group would study local stories, tracks and relics purported to be Yeti body parts in order to establish or disprove the legend. “Our ambition, of course, was to capture a live Snowman,” writes Doig. Hillary seemed more skeptical. “I think there is precious little in civilization to appeal to a Yeti,” Doig reports him as saying.

According to Sherpa legend, the yeti is a genus of high-altitude-dwelling, ape-like creatures with three distinct species: the dzu-teh is a six-to-eight-foot bearlike creature covered in either blond, red, black, or gray hair. Despite being largely vegetarian, dzu-tehs have been known to deploy its long claws in the hunting of cattle. The mih-teh is a two-legged creature the size of a small man and is covered in black or red hair with a long mane hanging over its eyes. Finally, Doig writes, the thelma is said to be a “sad-faced, dwarf-sized beast found in dense forests below 10,000 feet.”

The sheer amount of firepower taken along by the explorers demonstrates a significant sense of caution toward the animal that might or might not exist. Their armory included Cap-Chur guns capable of firing tranquilizer darts as well as rifles, shotguns, tear gas pistols, and “light arms.” “None of us particularly wanted to shoot one,” wrote Doig. “But we carried conventional rifles in self-defense as most accounts of the Yeti describe it as being savage in the extreme.”

The climbers and scientists were never called upon to defend themselves. The closest they came to encountering a yeti was the strange footprints they found in the snow. Located 20 to 30 inches apart, Doig writes, the prints seemed to be made “by naked human feet—size elevens or even fifteen, broad across the instep, fallen arches, and a big toe that protruded inward.”

Hillary dismissed the prints as having been made by snow leopards or wolves and claimed, “I would like a lot more convincing proof.” Doig, Swan, Perkins, and a few others set to work documenting the tracks with sketch books and measuring tapes, taking photographs, and attempting to make plaster of Paris casts, but it soon became clear that the prints were not made by a mysterious creature, but by the hot sun, which distended the tracks of much smaller, perfectly ordinary animals.

With the Yeti prints discredited, the only remaining “proof” came in the form of scraps of “relics” many locals seemed keen to sell at high prices, such as a “yeti hand” stored at a monastery in Pangboche; an analysis of a photograph revealed it to most likely be a human hand strung together with wire. Likewise, the numerous yeti skins shown to the expedition team—mostly blue-black with a white stripe across the shoulders—were widely agreed to belong to the Tibetan blue bear.

Three Yeti “scalps” held at local monasteries were the hardest pieces of evidence to disprove. After much wrangling, Hillary was given permission to take one scalp abroad for one month to be examined by scientists in Paris, Chicago, and London.

In this December 1960 photo taken in Calcutta, India, Hillary and sherpa Khunjo Chumbi examine a hairy scalp Himalayan villagers claimed belonged to a yeti.

Associated Press

“I have never believed in the existence of the snowman,” Hillary outright claimed in an interview conducted with Stars and Stripes at the start of the scalp’s scientific tour. But he did allow for the possibility he was wrong. “The scalp is hard to explain. It’s a convincing sort of specimen,” he says, likely out of deference to the Sherpa people. “The local people regard it as a yeti scalp and look upon it with respect.”

Eventually, the scientists agreed the scalp was likely a fake, possibly constructed from the skin of a serow, a goat-like creature found in the Himalayas. “Pleasant though we felt it would be to believe in the existence of the Yeti,” Hillary wrote in High in the Thin Cold Air, “when faced with the universal collapse of the main evidence in support of this creature the members of my expedition … could not in all conscience view it as more than a fascinating fairy tale.”

If Hillary had always doubted the existence of the yeti, why set off on a hunt at all? Ed Douglas, author of Tenzing: Hero of Everest and Himalaya: A Human History, suggests that Hillary used the headline-grabbing yeti hunt to get funding for the research portion of the expedition. “The yeti was a useful marketing tool,” writes Douglas. “I doubt Hillary really believed in it except when he was talking to PR people.”

Hoyland, who claims to have encountered a yeti footprint in Bhutan, believes otherwise. “Hillary was a mountaineer, and any mountaineer will jump at the opportunity to go and hunt for a yeti. I did, too.”

Whether Hillary’s Yeti hunt was a public relations stunt or something more, not everyone was satisfied by the expedition’s findings, which came as popular belief in the yeti’s existence began to fade. “I hope we are wrong about the yeti,” Doig wrote in High in the Thin Cold Air. “Whatever one may think of the legend… there certainly is something in the high Himalayas to spark the descriptions of a shaggy red monster walking usually on two feet.”