Gendarmes patrol Omar Bongo Square in southwestern Cameroon.Marco Longari/Getty

In August 2019, I wrote an article for the now-defunct Pacific Standard magazine about Martin, an asylum seeker from Cameroon who was denied protection by the United States and faced imminent deportation to a country torn asunder by civil war.

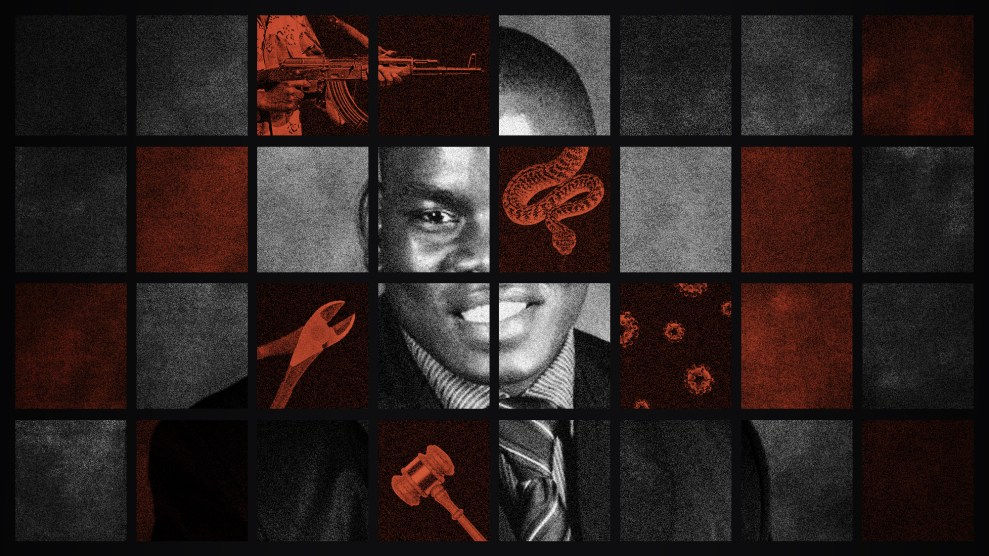

Martin, a member of the nation’s English-speaking minority, had taken part in demonstrations going back to 2016 denouncing the marginalization of the Anglophone population by the central government, which responded with deadly violence and began targeting protesters like him. Fearing for his life as the conflict between separatists and security forces that evolved into a full-fledged armed conflict in Cameroon’s southwest and northwest regions, Martin fled and traveled across South and Central America to reach the United States and beg for asylum. “It’s like living in hell there,” he told me at the time. “People are being killed like flies.”

An asylum officer determined that Martin had a credible fear of returning home. He was sent to an ICE detention center in Colorado, where he struggled with depression and panic attacks for months. Eventually, an immigration judge denied his request and ordered him deported, a decision that was affirmed on appeal.

But then, two months after my article came out, Martin’s case was reopened, which allowed him to resubmit his claims and provide additional evidence to the same judge. This time he prevailed, “ending a two-year odyssey through the depths of hell and into safety in the US, which still stands as a beacon of liberty to the persecuted and oppressed despite the efforts of the current administration to snuff out that lamp,” Martin’s lawyer said in an email, referring to the Trump administration.

But Martin was one of the lucky few. In a new report, Human Rights Watch documents the fates of dozens of Cameroonian deportees who returned to persecution and violence, including rape and torture, after they were rejected for asylum in the United States. The researchers identified 190 deportations to Cameroon in 2019 and 2020—about half of which were part of the mass deportation flights that sparked outcry in late 2020—and at least one in early 2021. As many as 39 of those who returned were detained by government forces, according to the report, and were sent to jails, prisons, and military camps, often without charges or a court hearing.

Researchers also learned of 13 instances of torture and physical or sexual abuse, with three of the women reporting they’d been raped after their arrest or during detention. “They took off my [clothes], so I was naked, and they beat me…for 14 days, every day…They were making me feel that’s the end of my life,” one recounted. Some deportees said they had been homeless or in hiding, and a few had considered suicide. “They destroyed our lives, the US government,” another deportee said. “How can you take someone running from war and throw us back where we’re running from?”

Those who sought asylum before they were deported were especially targeted, the report notes. Many said Cameroonian forces accuse them of “speaking ill” of the country, or of trying to destabilize and divide it. In several documented cases, government agents retaliated against their family members.

The humanitarian crisis in Cameroon, compounded by the presence of Boko Haram in the country’s north, has only gotten worse since Martin fled. So far, more than 4,000 people are dead as a result of the conflict, roughly 1 million are internally displaced, and more than 70,000 are registered as refugees in neighboring Nigeria. From the onset of the crisis up to the Trump administration’s public health order shutting down the southern border for most migrants, the number of Cameroonians seeking US asylum increased while the rates of asylum and other forms of immigration relief granted to them fell by almost a quarter. Most of the deportees interviewed by Human Rights Watch had appeared before immigration judges with higher-than-average denial rates.

The HRW report also documented abuse of Cameroonians in US custody, including the use of pepper spray, restraints, and solitary confinement against them. One person who spent three years in detention before being deported told the researchers an officer had knelt on his neck: “I told him I could not breathe. He told me he didn’t care.” Some deportees on the flights in late 2020 claimed ICE agents handed their identity documents on arrival to Cameroonian authorities, who confiscated the documents, limiting the ability of the returnees to get around, work, and access public services.

One of the women who reported being beaten and raped by military officers said they learned from her deportation papers that she had been in the United States. Others said ICE officers refused to let them discard documents before they boarded their deportation flights that could place them in danger at home. “In Cameroon, when we arrived…[police] asked, ‘Did you ask for asylum in America?’ I said no…They said I should shut up, that I was lying, because they found every piece of paperwork in my bag…proving that I asked for asylum…I was speechless…I wonder if those documents are the reason they later came” and beat me, one said.

In February, the Biden administration halted one deportation flight to Cameroon, but has since let the flights resume, despite worsening conditions in the region. Human rights advocates are asking that Cameroonians be designated for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and that deportees be granted humanitarian parole that would allow them to return to the United States, at least for the time being.