In the midst of a refugee crisis of over a million-and-a-half Ukrainians leaving their besieged country, there is another mass exodus underway. Terrified Russians, and foreigners living in Russia, are desperate to get out of a country that’s quickly descending into militarized authoritarianism, with an economy that’s entered into a downward tailspin.

Russians are sharing an Instagram story with advice on how to emigrate to the “free world.” Google searches in Russia for the word “emigration” have spiked. Andrea Palasciano, a reporter for AFP based in Moscow, tweeted: “Entering the phase of sending and receiving ‘Are you still here?’ texts.” Increasingly, the answer is “no.”

Moscow, day 9. Entering the phase of sending and receiving ‘Are you still here?’ texts pic.twitter.com/62YnAhjtEb

— Andrea Palasciano (@AfPalasciano) March 4, 2022

I have a privileged view of the situation because, as I write this article, I have completed the first leg of an emergency exit out of Russia. I’m sitting in a hotel lobby in Istanbul, eating a pita with mushrooms, and surrounded by Russian speakers who are also en route to anywhere that will take them that doesn’t happen to be in Russia.

There is lore in my family history that my great grandfather Isadore listened to Hitler’s speeches during the rise of Nazi Germany and decided that he needed to get his Jewish family out of Czechoslovakia. They emigrated to America months before the Nazis invaded the Sudetenland in 1938 and World War II began. A few of my grandmother’s extended family that remained there survived the camps, but most didn’t.

I have been thinking a lot recently about Isadore Liner, born Lenorovic before US immigration officials changed his name. If I had been my grandfather, would I have left Russia the night of Putin’s speech when he justified the unjustifiable invasion of Ukraine? One American I know who is married to a Russian and has a child says that ten minutes into the speech, they had all booked a flight to Georgia and were out of Russia two days later.

Since mid-November I have been living in Moscow as a journalist working for the Moscow Times as a participant in the Alfa Fellowship—an exchange program, funded by the Alfa Bank for American, British, and German citizens to study and work in Russia for a year. The program, founded in 2004, has survived despite the odds, as most of the Russian-American exchange programs that popped up in the wake of the Soviet Union’s fall have been canceled, unable to carry the legal risks and administrative burdens of operating in Russia. Alfa has been an exception.

But last week, only about a third of the way into the program, peace in eastern Europe went up in flames. Air spaces were closing, flights to Western cities were booking up or being canceled, foreign bank cards were frozen, and the fifteen Alfa fellows this year were told that we had 24 hours to get out. I imagine it didn’t help that Alfa Bank has been hit with sanctions and their CEO was one of the first oligarchs to speak out against the war.

The evening of Monday, February 21, was the beginning of the end. With just about everyone I knew in Russia, I sat in my apartment with my eyes glued to my computer screen, watching Putin’s televised security council meeting as they discussed whether to recognize the so-called people’s republics of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent; they were both technically part of Ukraine but controlled by what were referred to as “separatists.” Then Putin delivered his speech. His nationalistic ranting about how Ukraine was a fake state created by Lenin was one of the most chilling things I’ve ever seen. That same night, news trickled in that shelling had started in the Donbas region of Ukraine.

From that moment on, a sense of impending doom hung over Moscow that has not let up. I could feel it the next day at work in the Moscow Times newsroom, where I had just started working two weeks before. I could feel it among my colleagues in the Alfa Fellowship. I could feel it in the text messages I was starting to get from friends and family back home, asking if they should still plan to come to visit me in the spring. That was the night when the “Are you ok?” texts started.

On Tuesday, February 22, my boyfriend’s dad texted me the news that the US was going to cut off Russian bank accounts, after which point it could get difficult to make payments in Russia with a US bank card or to transfer money from my US bank account to my Russian Sberbank account. “Molly, keep your local account flush,” he said. I transferred thousands of dollars into my Sberbank account, thinking I’d need to load up for my remaining six months in Moscow. My boyfriend Peter was set to move to Moscow to join me on March 9, and I wanted to make sure there would be enough money for both of us. All the fellows received an email from the Alfa Fellowship administrators saying that they were monitoring the situation, but they weren’t planning to send us home until one of our respective embassies told us to leave.

Meanwhile, we had a fellowship trip planned. On the night of Wednesday, February 23, we boarded a 4.5-hour overnight flight to Altai, an epically beautiful region of Siberia nestled in the mountains between Kazakhstan and Mongolia. There were seven Americans, six Brits, and two Germans. We were journalists, political and financial analysts, green energy specialists, a lawyer, a teacher, and an artist, all interested in developing careers focused on Russia, eastern Europe, and Central Asia. We had all applied to this program back in January of 2019 or 2020, but getting started was delayed for months and months because of the coronavirus pandemic and closed borders. We started language training in June of 2021 and moved to Russia in mid-November eager to learn the language, meet Russians, and do our bit to bridge the growing divide between Russia and the West.

Altai, an epically beautiful region of Siberia nestled in the mountains between Kazakhstan and Mongolia.

Molly Schwartz

In between the various security checks at Domodedovo airport on the outskirts of Moscow, we talked about Putin’s crazy speech and the fireworks display going off over Moscow that night in celebration of Defender of the Fatherland Day. The flight was packed. When we landed in Alta at 9 a.m., running on a couple of hours of sleep maximum and having jumped four times zones—it was then 5 am in Moscow—we tried to catch up with the news. Blearily guzzling coffee and eating a lukewarm blini, I heard from a journalist friend who had checked Twitter that explosions were going off in cities all over Ukraine, including Kyiv.

It was one of those moments that cleaves your life into a before and an after. Before, this part of the world was at peace. Now, it was at war. The sanctions started rolling in. The death count mounted. Germany, long trying to play neutral, shut down the Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

My friends and I were alternately stunned and crying, checking in with friends in Ukraine and wondering how we were going to access our money. Would we need to go home? Would we be able to book flights? Many people on my program were connected to Ukraine because they had Russian teachers from there, who either still live there or have family there. The fact that Putin was justifying this war because Ukrainian Neo-Nazis were supposedly beating up Russian speakers in the streets was a sick irony that was not lost on any of us.

As we were carted around in pickup trucks through the breathtaking mountains of Altai, my 14 friends and I were glued to our phones, watching people around the world wake up and react. The trip felt like a funeral. We all knew that our days in Russia were probably numbered, but we were far from Moscow and unsure how quickly things would devolve.

Altai is known as the Las Vegas of Siberia, and on our last night there we stayed at the Altai Palace Caison. The art deco sign blazed golden over the hotel, its parking lot full in this strange watering hole nestled in the Siberian mountains. None of us were in the mood to gamble, so we ordered huge beers and Siberian-themed cocktails, with ingredients like cranberries and sea buckthorn (a medicinal shrub found in Eastern Europe and China), and huddled around a small table in a room filled with Russian billiards (which is even harder than American pool, which I find challenging enough). We had to leave at 7 am the next morning, but we knew this was probably the last time we’d ever sit around a table and share a drink. It was one of those moments when life feels short and friendships fleeting, when you need to grab onto precious moments with ones you love and figure you can sleep when you’re dead.

The Altai casino.

Molly Schwartz

I woke up at 5 a.m. on Sunday to an email that told me the program was ending, and we were all being immediately booked on flights out of Moscow through Istanbul. Tired, a bit hung-over, deeply apprehensive, and sad, we all headed to the tiny airport in Gorno-Altai where our flight was delayed for two hours. There weren’t enough spaces for all of us to sit in the waiting area, so half of us sprawled on the floor, the other half paced and called friends and family at home, trying to concoct some reasonable plan on the fly.

We had all left our jobs, our apartments, our homes, expecting to live in Moscow until December 2022. Now that was impossible. We had twelve hours to get packed and get out.

I finally arrived back at my apartment at four in the afternoon and started packing. I was extremely lucky; Moscow was only ever a temporary home for me. I didn’t have furniture or family or years of belongings. But even so, the entire experience was surreal. The things that had mattered only a few days ago—my apartment registration forms, my office entry card, my “friend of the Pushkin Museum” membership, my troika card with unlimited trips for the next months—were all completely useless. In only a few hours, plans and expectations had been completely upended.

When I arrived at Vnukovo Airport airport, we waited in a slow-moving line to pay to check an extra bag with Russians, who were as anxious as we were about whether we could pay in rubles or euros. The woman at passport control stared at my visa for an uncomfortably long time and made a phone call, which isn’t what you want at passport control, before finally waving me through.

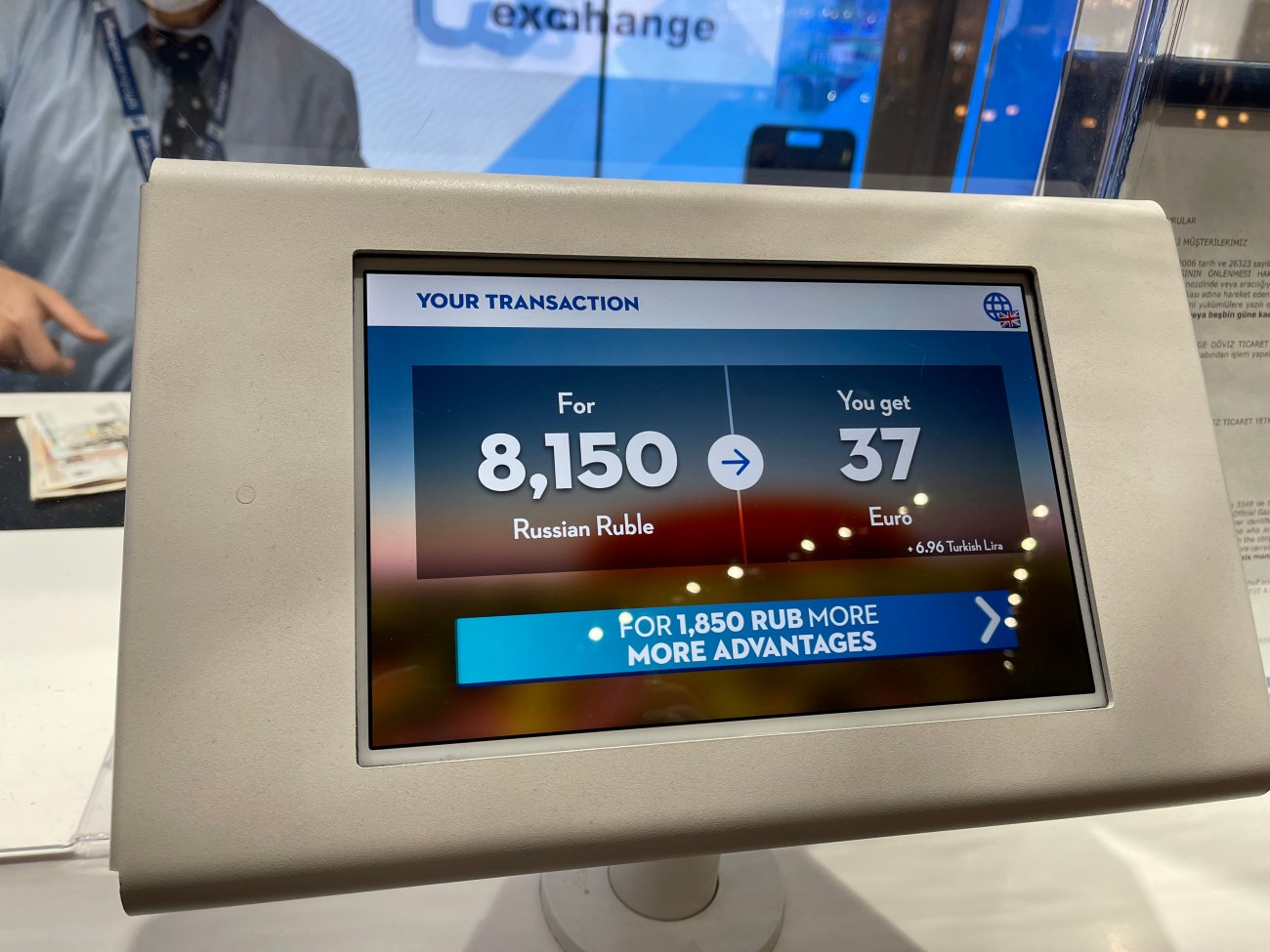

I was one of the fortunate few. Ukrainians are watching their homes get bombed and shelled. They are fleeing for their lives, on crowded trains with old people, or small children, and no possessions beyond what they can carry. Journalist colleagues are sleeping in bomb shelters in Kyiv. Russians are getting arrested by the thousands and standing in long lines at ATMs, watching their life savings disappear as the ruble tanks. Their isolation from the rest of the world is increasing as independent and Western news outlets from Echo of Moscow to BBC are shut down or blocked.

I’m hearing stories of families and relationships being torn apart. The Ukrainian woman who fled with her son on an overnight train to Poland while the father stayed behind to fight. The American man who was in the process of getting a ring made in Moscow when he and his Russian girlfriend had to pick up and leave, moving to Istanbul, one of the few places where Americans and Russians can both live for a few months with an easy-to-obtain visa. The British woman who offered to marry a Russian guy she’s been on a few dates with so that she could get him a visa.

The terrible exchange rate as the Russian Ruble tanks.

Molly Schwartz

The reverberations of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have extended well beyond its borders, completely upending any sense of security in Eastern Europe. My friends in Finland, where military service is mandatory for men, are wondering if they’ll be conscripted in the near future. Friends across the region, from Estonia to Moldova, are seriously wondering if Putin will use thermobaric or even nuclear weapons, which he has made veiled allusions that he’s willing to do, even ordering commanders to put nuclear weapons on a “special regime of combat duty alert.” There are rumors in Russia that the government could start terror bombing cities and make it look like a Ukrainian attack, or implement martial law and close the borders so that no one would be able to leave.

After a three-hour flight, I arrived at Istanbul’s airport, with its piles and piles of duty-free Turkish delight that I had to exert some self-control not to buy. I was laden with luggage and a few thousand practically useless rubles in cash, just trying to figure out how I was going to spend the next few days, much less the next months. Friends abroad messaged about relatives in Ukraine who were trying to get out, while friends in Russia were messaging that they weren’t able to get money out of accounts, while the cost of flights out of Russia was skyrocketing. Then, aside from the military conflict in Ukraine, there was a refugee crisis unfolding in Europe the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the massacres in Syria. So while still at the airport, I booked a flight to Helsinki where I could recuperate for a couple of weeks. Freshly without a job, but with a few offers from editors to do freelance reporting from the region, I decided to head to Poland to report on the situation.

The huge Istanbul airport has become a popular stopover for people trying to get out of Russia.

Molly Schwartz

The signs of what was going to happen were everywhere. Person after person I’ve talked to, across countries and time zones, wondered how we didn’t see Putin’s reckless invasion coming after he has been saying for years that Ukraine is a part of Russia, that the greatest historical travesty was the fall of the Soviet Union and Russia’s loss of all that territory.

Over the last decade, the climate in Russia has gotten more and more difficult for foreigners, from business people getting arrested to journalists getting ejected. Plus, there are still administrative demands that feel like holdovers from Soviet times, such as stringent rules about foreigners registering every time they enter a new city. People on the fellowship with me had issues finding apartments that were available to foreigners, or Russian workplaces that would let foreigners work there. And, perhaps most bizarre and unsettling of all, the Russian government implemented a new scheme in December whereby all foreigners working in Russia were required to go to health checkups every three months, which include a Covid swab, drug testing, and invasive STD screenings.

Now in Istanbul, I thought about my hasty departure. As I packed up my life, it was hard not to feel as if I had managed to catch the last plane out before an iron curtain once more fell over a country I have come to love. But this iron curtain contains not even a whisper of an ideology. Instead, it is made from a paranoid leader who is so suspicious of foreigners, so intolerant of political dissent, so hungry for power, that he will kill and impoverish his own people. Will Russia be completely cut off from the world? With foreign companies pulling out and airspaces being closed, are food and medical supply shortages inevitable?

Despite all the overtly anti-American propaganda playing on Russian state TV all day, every day, saying that the Americans are running special ops in Ukraine or abandoning their allies in Afghanistan, I never met a single Russian who treated me badly, who discriminated against me, or even seemed suspicious because I am American. They were, without exception, pleased that an American was there, and showered me with undeserved compliments about my attempts to learn Russian. They were warm, open, and curious, happy to welcome an American with a vodka shot, so many varieties of beet-based salads and soups, and a banya session if I was lucky. The government depends on sustaining an “us” versus “them” mentality. But with so many Russians trying to get out, with so many Russians horrified by what is being done in their name, you have to wonder who the “us” even is anymore—or the “them.”