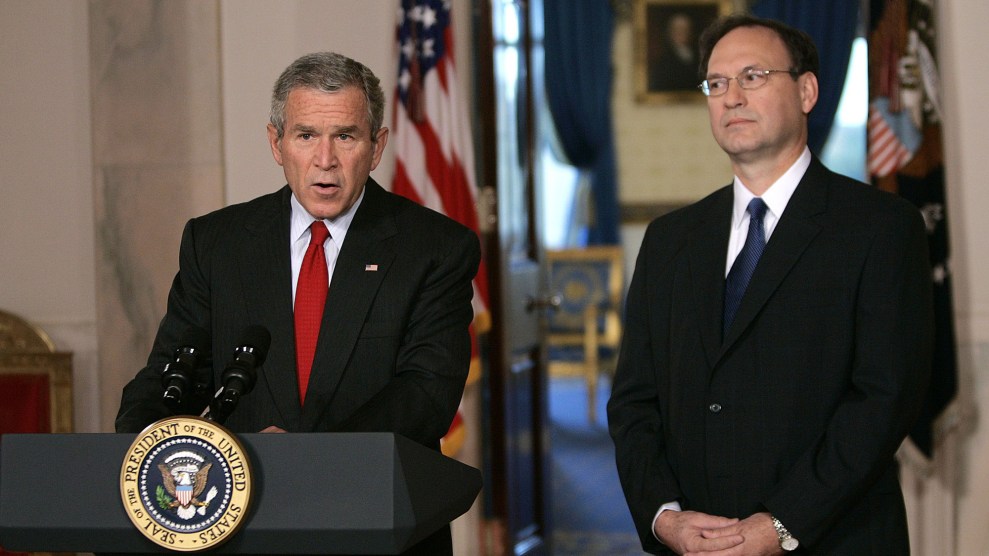

President George W. Bush introduces Alito as a Supreme Court nominee.Chuck Kennedy/TNS/Zuma

Republicans successfully transformed the confirmation hearing of the first black woman nominated to the Supreme Court into an abusive circus based on a malicious lie, all to get on Fox News and light up the QAnon corners of the internet. By taking a handful of cases out of context, Republican senators accused Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson of being soft on child porn defendants. Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Missouri) claimed in a tweet last week, as he set up his party’s strategy to enmesh her in a meritless scandal, that Jackson has “a pattern of letting child porn offenders off the hook… a record that endangers our children.”

The Republicans’ concern over a non-existent problem stood in stark contrast to another not-so-distant Supreme Court confirmation hearing in which child endangerment was a legitimate issue. In 2006, it was Democrats who were concerned, alarmed by the record of nominee Samuel Alito, a hyper-conservative circuit court judge with a record of deferring to law enforcement, even, as in one case, when a police officer strip searched a child in the course of a drug raid. Democrats raised the issue during the hearing—while Republicans remained almost entirely silent.

The case went back to 1998, when police officers in Pennsylvania executed a drug raid in which the suspect’s wife and 10-year-old daughter were strip searched. The family sued, alleging an illegal search under the Fourth Amendment. The majority of the circuit court’s panel agreed, reasoning that the warrant did not list the wife and daughter. But Alito dissented, arguing that because a magistrate judge had attached an affidavit to the warrant that said the search “should also include all occupants of the residence,” that the police had the authority for the additional searches and, at bottom, could reasonably assume that they did. Despite concern among Democrats over Alito’s dissent, many legal experts gave him the benefit of the doubt in the lead up to his confirmation hearing, generally voicing the argument that this was a highly technical case, not one in which Alito seemed to favor strip searching children.

But when Democrats questioned Alito about the case during his confirmation hearing, his comments were more concerning than his ruling. Repeatedly, Alito conveyed that searches of minors should be allowed—presumably, as in the case in question, including strip searches. “I was concerned about the fact that a minor had been searched. And I mentioned that in my opinion and that is something that is very unfortunate,” Alito told Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill). “But the issue in the case was not whether there is some sort of rule that minors can’t be searched. That is not part of Fourth Amendment law, as I understand it, and there would be a very bad consequence if that were the rule because where would drug dealers hide their drugs? Minors would then become—they would become the repository of the drugs and the firearms.”

The more times I read this quote, the more disturbing Alito’s position became. He seems to argue that children should be searched to deter suspects from hiding evidence on them. For raids to work, they are supposed to surprise the suspect. Does he believe drug dealers would store their guns and contraband on their children as a matter of routine, whenever they are home? Whenever they go to bed? Would anyone treat children as trusted custodians of valuable and dangerous objects such as drugs and guns? Does he think all drug dealers are so despicable as to endanger their children in this way? I suppose it’s possible that some might, if police banged on the door, pass a gun or bag of contraband to a teenager to hide under their shirt.

While the idea that children should be searched—or even strip searched—to deter suspects from stuffing evidence down their kids’ pants is deeply troubling, no Republican at the hearing worried about the possible consequences of Alito’s reasoning. If cops could strip search children, without a warrant, and face no repercussions, it seems reasonable to predict that more children could be subject to more unlawful and traumatic searches. Republicans could have posed the same line of questioning to Alito as they have to Jackson: would his decision—his leniency toward the cops—have endangered children?

Back then, only one Republican serving on the Senate’s judiciary committee raised the case, Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.), who came to Alito’s defense and downplayed the trauma of the strip search. None of his party colleagues seemed to have any hesitation about Alito’s decision approving the search, or his comments doubling down at his hearing. This includes three Republicans who still serve on the panel today and had no hesitation about using their position to push the claim that Jackson’s record on child pornography endangers kids: Lindsey Graham, John Cornyn, and Chuck Grassley.

Witnesses for the Democrats, on the other hand, were disturbed by Alito’s ruling. “Senators, any police officer, any judge should know that strip-searching a 10-year-old girl who is suspected of nothing violated the Constitution,” legal scholar Erwin Chemerinsky told the panel.

Alito, of course, was confirmed. He is now a Supreme Court justice. Jackson will likely join him—but only after a far more degrading and offensive process that, unlike in his hearings, has centered a controversy without any basis in fact.