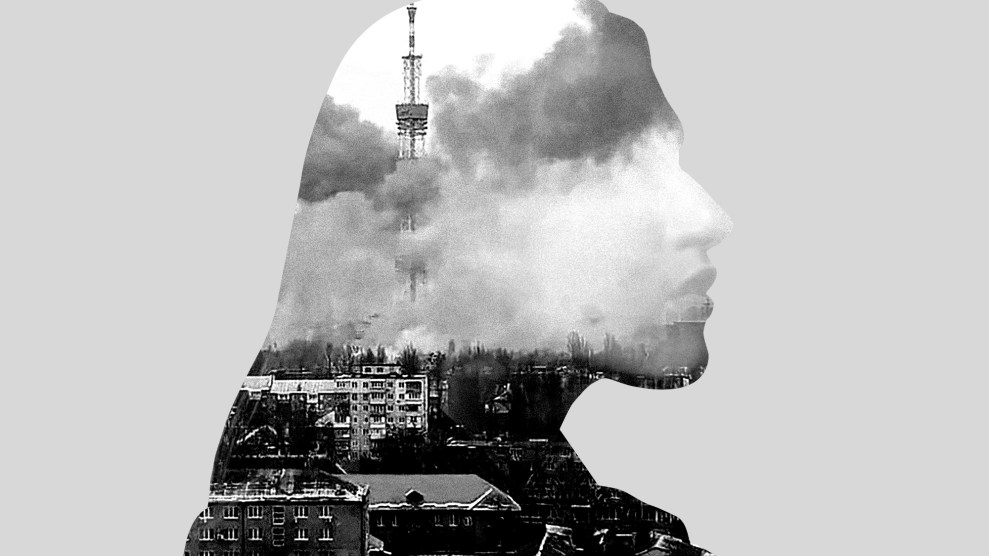

Women and children wait to board a bus heading to Przemysl after fleeing Ukraine.Visar Kryeziu/AP

On March 3, a Spanish TV station filmed several guards beating and kicking an African migrant as he climbed down a border fence separating Spain’s enclave of Melilla and Morocco. The video went viral on social media, and migrant rights advocates promptly noted the jarring discrepancy between that display of violence and the country’s readiness to welcome Ukrainian refugees as “full citizens.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has already forced more than 2 million people, including hundreds of thousands of children, to flee, and the United Nations refugee agency projects that number will double. The majority of refugees have crossed into Poland and other neighboring countries like Hungary, which have track records of brutally turning away migrants and leaving them trapped at the border in inhumane conditions.

📺 Estas dos últimas jornadas en #Melilla con los dos saltos a la valla nos están dejando imágenes cómo estas. @rtvenoticias pic.twitter.com/baATJZA8zt

— RTVEMelilla (@RTVEMelilla) March 3, 2022

The world has been watching in horror the bombing of a maternity hospital, the loss of civilian lives, and the stories of fathers remaining to fight in Ukraine, while mothers and children flee. And, rightfully so, Ukrainians have been met with unparalleled expressions of individual and international solidarity. Strangers have left strollers, clothing, and toys at train stations and have volunteered from all over Europe to help the arriving refugees find housing and other support. Last week, for the first time ever, the European Union invoked a 2001 directive offering temporary protection and access to housing and other benefits to fleeing Ukrainians and foreigners with refugee or permanent residence status in Ukraine. “The response by Europe has been remarkable,” the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi said.

But examples of racism and double standards have also been rampant. Non-Ukrainian refugees have reported that they had been denied the right to board trains and buses to cross borders and described how authorities separated white and nonwhite people at ports of entry. Meanwhile, media pundits and public figures have been propagating harmful and discriminatory comparisons between the refugees they deem to be deserving and undeserving. “These people are Europeans…these people are intelligent, they are educated people,” the prime minister of Bulgaria said. “This is not the refugee wave we have been used to, people with unclear pasts, who could have even been terrorists.”

For years, Lamis Abdelaaty, an assistant professor of political science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School, has been researching the ways in which countries fashion their refugee policies. She has focused on trying to answer the question: Why do countries open their borders to some refugee groups while blocking others? In her book Discrimination and Delegation: Explaining State Responses to Refugees, she writes: “Policymakers will adopt generous policies when refugees are fleeing a hostile state and share the policymaker’s ethnic identity. They will adopt restrictive policies when refugees are fleeing a friendly state and do not share the policymaker’s ethnic identity.” I spoke with Abdelaaty over the phone about Europe’s reception of Ukrainian refugees, and how the framing and labeling of different migration movements shapes international responses to them. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How does looking at previous refugee crises help us understand the factors and patterns shaping nations’ responses to current and future refugee flows?

I started working on the book in 2009, so before the Syrian refugee crisis. It was at a time when large-scale refugee movements weren’t necessarily on the radar of many political science and international relations academics, even though there was a big Afghan refugee population in Pakistan and Somali refugees that had been displaced. We have a tendency to think of countries as being either generous, receptive, and welcoming or restrictive and closed down. I say in the book that’s not really accurate. Almost every country in the world discriminates amongst different refugee groups. We’re seeing this very welcoming, receptive response to Ukrainians, and I think it’s important to recognize that these numbers reflect the fact that people are able to flee and are able to cross borders. It really brings to the fore this very stark contrast with 2015 when we saw various European countries respond to the arrivals of people, predominantly from the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, with closed borders and pushbacks. It also is a very stark contrast with Poland’s very recent treatment of people stranded on its border with Belarus.

In your book, you propose two reasons for this selective exercise of sovereignty where states open their borders to some refugee groups while blocking others. What are they?

My book emphasizes the role of identity and the role of foreign policy, and I think that those two factors help us understand what’s going on today with Ukraine. In general, people tend to sympathize with refugees who they think share their identity. Europeans identify with the Ukrainians. They see them as a similar group of people: They’re white and Christian, and there are shared cultural and historical ties. Syrians and Afghans are not perceived this way. But that’s not the whole story. There’s a foreign policy dimension to it as well. It matters that the Ukrainians are fleeing a Russian invasion. Welcoming them is a way for European countries to signal the fact that they condemn Putin and that they are on the side of Ukraine in this context.

We’re also seeing this very quick and clear tendency to label Ukrainians as refugees, which is striking because most Ukrainians actually wouldn’t qualify for refugee status under the 1951 Refugee Convention, which requires people to be persecuted rather than fleeing generalized violence. This choice of labels matters because ordinary people are more accepting of those who are labeled refugees. They view them as more deserving than those who are labeled migrants or immigrants, who are perceived as voluntary border crossers. But obviously, this term isn’t being used equitably across different groups, who we could certainly think are being forced to leave their countries because of gang violence, or because of climate change, or because of destitution and economic difficulty. We’re also seeing differences in the way that the word “crisis” is being used. When people are talking about the Ukrainian refugee crisis, they’re predominantly referring to a crisis for Ukrainians which, in my opinion, is the correct way to use this term. But we can compare this with 2015, when people were talking about “Europe’s migration crisis” or “Europe’s refugee crisis,” and the implication was that the arrival of people was posing a crisis for European countries, rather than it being a crisis experienced by the Syrians, the Afghans, and others.

For the first time, Europe has invoked a 2001 temporary protection directive giving temporary status and benefits for Ukrainians. Why wasn’t that provision extended to Syrians, for instance?

We could have imagined the European Union responding in 2015 in a very similar way to how they’re responding now: Making sure that people are able to arrive safely, able to cross internal borders within the EU, mobilizing to provide social welfare and other support, and then invoking the temporary protection directive to ease the burden on countries’ asylum policies. But I think part of the reason that we didn’t see that is that for many European countries, this was not a desirable group. They’re seen as others, they’re not, quote-unquote, like us. As a result, they’re viewed as a potential threat and there is no foreign policy gain to be had from admitting them. We’ve seen a lot of people in the media talking about the Ukrainians, referring to them as quote-unquote, civilized, blonde with blue eyes. They talk about the fact they’re prosperous, middle-class Europeans. People are scrambling for a way to say that the Ukrainians are like us, and we think that they’re more deserving of our compassion. War and displacement happen over there, far away. It’s not supposed to happen here. And the fact that it’s happening here is sort of being interpreted as people look at these refugees, as well, this could be me, This looks like me, or this child looks like my child.

So far, authorities and civil societies across Europe have welcomed Ukrainian refugees with open arms. Do you see that sentiment potentially subsiding over time as the conflict drags on and the number of people settling in neighboring countries continues to climb?

If it becomes more apparent that maybe Ukrainians will not be able to return as quickly as people thought, and as there are fresh rounds of elections in various European countries, it’s possible that we’ll see a cooling in the very welcoming sentiment that’s been exhibited so far. We’ve seen similar trends in other countries like Turkey with its initial enthusiastic embrace of Syrian refugees. This conflict really shows that the European Union is capable of responding to large-scale population movements. It would be wonderful to see people holding their governments accountable for living up to the values that they purport to stand for.

What has been most striking for you about the media narrative and public discourse regarding the Ukrainian refugee crisis?

What has been surprising to me is how unabashedly the discrimination is between these two groups: Ukrainians on the one hand, and then people arriving in 2015. Not just the media, but political figures have said well, the reason we’re welcoming Ukrainians is because they’re not people from the Middle East. The fact that we’re seeing this double standard commented on so explicitly is something I wasn’t expecting to see on full display. The scenes coming out of Ukraine are horrible, heart-wrenching. Like many people, I’m genuinely delighted that European countries are being welcoming. Ukrainian refugees need whatever assistance we can provide them with. But we all really need to think about the fact that these same images that we’re seeing coming out of Ukraine—people carrying whatever they can, leaving everything else behind, sometimes leaving family members behind, walking very long distances, having to shelter from the elements—we’ve seen them with other crises elsewhere in the world. And yet they are provoking such a different response. We need to bring the same empathy to other refugee groups who are escaping very similar conditions and who are equally worthy of our compassion.