On a chilly evening in September 2020, Jordan Schumacher solemnly patrolled the grounds of Valley Forge Military Academy, near his wit’s end. Weeks earlier, the school’s top brass had elevated the 20-year-old college sophomore to the highest rank available to cadets—first captain. A former Boy Scout who’d joined a junior ROTC program at age 11, he was proud of the promotion and ready to lead. But as he navigated the school’s toxic environment in his new role, he’d been feeling increasingly helpless and depressed.

Entrusting students in leadership roles was all well and good, but a dearth of healthy adult oversight and accountability had contributed to a culture replete with assaults, verbal abuse, hazing, and sexual violence that had resulted in police visits, lawsuits, and a cold war pitting recalcitrant trustees and administrators against reform-minded parents, alumni, and cadets. Out on patrol that night, Schumacher told me, he felt on “the brink of darkness.”

The Forge, as insiders call it, resembles a cross between an East Coast prep school and a military installation. Its 100-acre campus is dotted with dormitories and academic buildings, but also with a war memorial, an obstacle course, and a parade field for drill formations. Nestled 20 miles north of Philadelphia, the private institution teaches middle school, high school, and junior college students. Some graduate as commissioned military officers, but all are subject to the customs and courtesies of military life, as well as its trials and traumas.

With school leaders doing little to address the fraught campus atmosphere, Schumacher had taken it upon himself to patrol the grounds as often as possible. This evening, walking along a mossy brick pathway, he spotted something suspicious: Behind a storage shed, out of sight of campus surveillance cameras, a group of upperclassmen was tormenting a few shivering plebes.

He’d stumbled upon an unsanctioned version of the “cap shield” exam, an induction rite wherein new students are quizzed on the Forge’s nearly 100-year history. The exam is the culmination of a boot camp of sorts for incoming college students. Those who pass are welcomed into the Corps of Cadets, which Schumacher now commanded, and rewarded with the cap shield medal, a brass badge depicting the mythical moment when General George Washington, standing on the Pennsylvania battleground for which the school was named, prayed for the survival of the fledgling American republic.

Schumacher had arrived on campus in 2019, excited by the Forge’s time-honored traditions and drawn to its curricula on counterterrorism and cybersecurity. A stocky history nerd with dark brown hair, he spent hours memorizing school trivia and passed his cap shield exam in near-record time. But he soon came to see the exam as an empty ritual. It revolved around lofty principles, yet often culminated in a “cap shield handshake,” wherein plebes point the prick of the badge toward their palm and accept a vigorous clasp. A minor stabbing, perhaps, but telling of more extreme hazing that campus leaders seemed willing to tolerate, and sometimes even take part in.

When Schumacher disrupted the hazing session, the plebes were relieved, the bullies annoyed. Afterward, one emailed him a screed claiming he lacked the traits of a US Marine. “That pissed me off,” Schumacher recalls. “These cadets were clearly out of line. They had the wrong idea of what service and tradition really are.” But he was even more frustrated with the school for creating an environment in which college kids were saddled with responsibilities beyond their age and experience. Cadets were meant to be supported by adult TAC (teach, advise, counsel) officers, many of whom are military veterans. Yet in recent years, Forge administrators had laid off some of the best TACs and replaced them with less-enlightened ones. “We were no longer in the military. We were civilians,” notes one Marine veteran who worked as a TAC from 2005 to 2019. “We were there to be a role model for these kids, not a drill instructor. Many of my co-workers didn’t understand that. They ruled by intimidation and fear.”

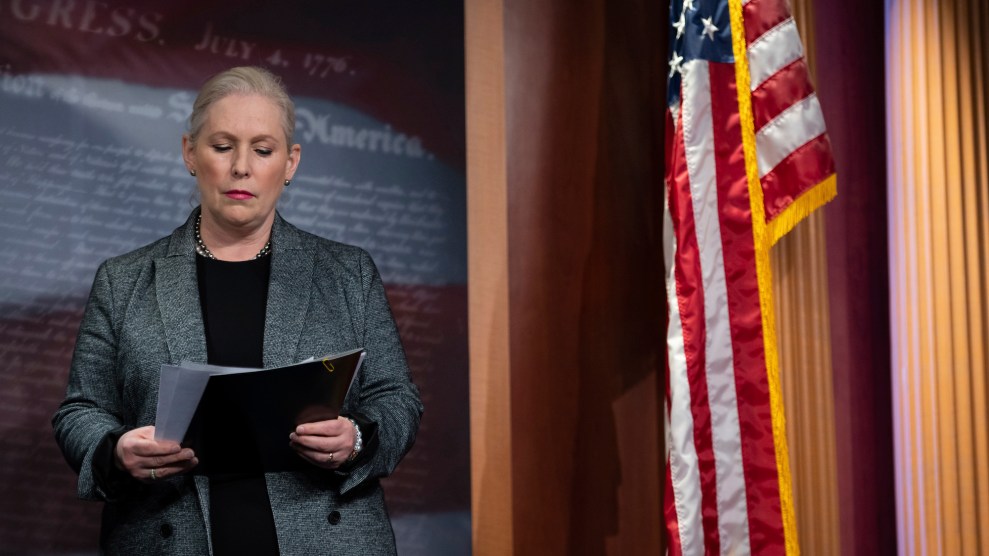

Jordan Schumacher

Devin Oktar Yalkin

Schumacher and a handful of other cadets thus took it upon themselves to shield fellow students from bullies and twisted TACs alike. They did their best to prevent fights, and would rush injured kids to the hospital. One filled in as school chaplain, holding religious ceremonies and counseling suicidal cadets as young as 13. These self-appointed protectors also stayed with students experiencing mental health crises to ensure they didn’t harm themselves, and organized shifts to track down comrades who had fled the campus—a frequent occurrence. “It’s kind of like prison,” one former student said.

Schumacher found respite at the stables, where he and other members of the school’s mounted battalion spent hours each week “dealing with the horses” and “dealing with ourselves.” He almost dropped out when the Forge, to cut costs, abruptly disbanded its cavalry and repurposed the polo arena for paintball. But it was confronting the cap shield bullies a few days later that sent him over the edge. Schumacher stormed back to his dorm afterward, gathered his belongings, and threw everything in his truck, yelling and banging doors as he vented his rage. As he sped off, he began crying. He didn’t know whether he wanted to go on living: “I was just mentally shattered.”

His friends found him later, parked on the roadside in a state of shock, and urged him to come back to campus. (Ten other cadets went AWOL that weekend, some for a temporary taste of freedom, others hoping to escape permanently.) Schumacher returned to the dorms but quit the school for good soon after. Now a bona fide Marine, he believes Valley Forge fashions leaders only insofar as it exposes cadets to behavior unbecoming of an officer. “It brings out the best and the worst in people,” he told me. “I don’t want to say that’s a goal of the school, but it’s something that happens. It showed me who I didn’t want to be.”

“Underweight” cadets receive milk and cod liver oil, circa 1933.

Bettmann Archive/Getty

Valley Forge has long billed itself as the kind of institution that breaks young people down in order to build them back better. Many business, political, and military leaders have embraced that tough-love approach. As alum General Norman Schwarzkopf, architect of the first Gulf War, put it, “West Point prepared me for the military. Valley Forge prepared me for life.”

The Forge has churned out other bigwigs, including Gustave Perna, the retired four-star general who led the Operation Warp Speed vaccine push, and General H.R. McMaster, Donald Trump’s former national security adviser. But most famous of all is the novelist J.D. Salinger, whose parents sent him to the Forge in 1934 after he flunked out of a Manhattan prep school. It was here Salinger honed his writing skills—a sentimental poem he wrote about the school is still recited at its gatherings. His masterwork, The Catcher in the Rye, opens with Holden Caulfield at Pencey Prep, a fictionalized version of the Forge. Aspects of Salinger’s rendering ring true to cadets today, from the “crumby” food to a culture of bullying and entitlement perpetrated by “phonies” and “crooks.” “It was a terrible school, no matter how you looked at it,” Holden observes.

The fictional Pencey maintained strict rules and excellent academics—virtues, if ones Holden couldn’t live up to. “I got the ax,” he informs readers. “They give guys the ax quite frequently at Pencey.” These parts of Salinger’s depiction no longer seem so apt. According to internal documents, police records, legal complaints, and interviews with more than 50 sources close to the school, including current and former cadets, parents, staff, and board members, campus leaders have allowed an environment of neglect, abuse, and impunity to fester.

While rule breakers once got the ax, staffers have allegedly overlooked serious misdeeds while retaining the offending students and banking their tuition dollars. (Tuition, plus room and board, starts at just under $38,000 per year for middle and high school and $48,000 for college.) One student stabbed a classmate with scissors; another bashed his peer with a baseball bat—neither met serious repercussions. Once a citadel of leadership, Valley Forge today is “basically a sleepaway camp for troubled kids with very little supervision,” says graduate Ray Bossert, a retired Army colonel and former TAC. “It’s more Lord of the Flies than The Catcher in the Rye.” Walt Lord, a popular but short-lived school president, agrees: “It became ‘Last Chance U,’ which was a revenue driver but also cancerous to the Corps of Cadets.”

Amid money woes, administrators have curtailed sports, slashed courses, and assigned teachers to unfamiliar subjects, leading to an academic decline so steep that some Forge cadets complain certain colleges no longer accept transfer credits for many of their courses. The campus is crumbling, too, its barracks periodically infested with rats, cockroaches, and mold—cadets have also complained of burnt and moldy food in the dining hall. Lawlessness is commonplace. Over the last four academic years, the Radnor Township Police Department has responded more than 300 times to incidents on campus. Police reports obtained by Mother Jones from the last decade involve cadets as young as 13 experiencing psychiatric crises, including suicidal behavior. In 2016, an 18-year-old cadet took his own life in Lafayette Hall.

The police data, and campus security logs, document a litany of allegations, including assault, arson, burglary, larceny, narcotics and weapons possession, stalking, and rape. A recent post on a private Instagram account titled “Valley Forge Sucks” shows two cops peering into a schoolroom, with the caption: “Normal day at the Forge.”

Valley Forge administrators declined to respond to detailed questions about the concerns raised in this story, or to make named staffers, administrators, or trustees available for interviews. Citing privacy concerns, retired Marine Col. Stuart Helgeson, the school’s president, said in a statement that the Forge has “zero tolerance for hazing and illegal and inappropriate activity,” “thorough policies and procedures in place to address allegations of wrongdoing,” and “a proven track record of taking action to address concerns quickly and appropriately.” The school, he added, “will continue to manage matters that arise according to law, policy, and the best interest of the cadets entrusted to our care.”

School trustees and senior administrators, according to legal documents and numerous sources, have minimized rather than remediated the problems. An institutional focus on protecting the Forge’s reputation above all else has created, in the words of one former teacher, “a chocolate-covered onion.” Amid a steady drip of scandals, lawsuits, and pissed-off parents, leaders have clammed up, countersued, and compiled a list of perceived enemies who are barred from campus. Officials “constantly worried about themselves and covering their own asses,” says a former longtime TAC. “All they cared about was that there was no negative press, even if it meant that kids were being sodomized or kids were having inappropriate sexual relations, or getting drunk or getting high, or whatever. They didn’t care.”

A twisted drill sergeant mentality took root. One TAC extinguished a cigarette in the palm of an underage cadet caught smoking, a former administrator told me. A former TAC said he nearly came to blows with a colleague who’d beaten up a 14-year-old. In 2015, the school’s then–Title IX officer warned of a “‘Gomer Pyle’ method of training,” referring to a character from Full Metal Jacket whose brutal hazing by others pushes him to commit a murder-suicide.

In addition to recruiting military personnel, the school brought in former cops and prison guards to oversee cadets. A couple of the TACs came from Glen Mills, a Pennsylvania penal school that the state shut down in 2019 amid allegations of child abuse. Bossert and another former TAC singled out one Glen Mills colleague whom the Forge hired in 2016. This officer frequently got physical with students, according to his former co-workers, one of whom distinctly recalls him body-slamming a cadet in the mess hall.

Another controversial figure is J.J. Rivera, until recently the school’s commandant, or head TAC, whose verbal attacks on cadets and flirtatious behavior with female cadets raised eyebrows. In a grainy video recently shared on the Valley Forge Sucks Instagram, Rivera, now chief of staff, can be heard screaming “Shut the fuck up!” at a whimpering young cadet. He then grabs the boy.

Schumacher and another former cadet remember Rivera at one point declaring his intent to give cadets an experience the commandant likened to a deployment in “one of the shit-istans.” This consisted of TACs berating and belittling the cadets and robbing them of sleep. “It was, ‘Toughen the fuck up! If I hear you have problems, then fucking leave…I don’t need a broken soldier,’” another former cadet recalls.

Several alumni who serve in the armed forces told me that nothing in their military experience has been as harrowing as their years at the Forge. Young Sheng, a 2015 graduate, recalls a punishing world of sleep deprivation, verbal abuse, and “smoking”—extreme physical conditioning that caused cadets to puke and pass out. The mistreatment “amplified my anger issues,” Sheng said, and led him to abuse others in turn. “It’s extremely negligent to let students have this level of power over each other’s lives,” he said. “The culture was rife with abuse of every part of a person’s being.” Recalls another alum: “I didn’t feel like a human the majority of the time I was there.”

A rappel tower the Army constructed on campus for its Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC), a program in which Valley Forge no longer participates.

Devin Oktar Yalkin

Formal military education emerged in Europe during the 18th century and was embraced by the colonial brass during the Revolutionary War. “We are fighting against a people well acquainted with the theory and practice of war, brave by discipline and habit,” American General Henry Knox wrote in 1776 to John Adams, who then chaired the Continental Congress’ Board of War. Knox argued that the new republic needed to bring its own soldiers up to snuff at any expense.

In response, the Continental Congress promptly developed the first Army academy, West Point. Major Sylvanus Thayer, an early superintendent, set forth the standards by which US military schools would henceforth operate, building fighting men through a curriculum of tactical engineering, physical training, strict rules, and harsh discipline. According to Cadets on Campus, a history of military schools, Thayer defended his commandant, Captain John Bliss, after Bliss brutally assaulted a cadet. When cadets circulated a petition demanding Bliss be held accountable, Thayer expelled its 189 signatories and court-martialed the five organizers for leading a “mutiny.”

The incident helped codify a punitive atmosphere that has plagued military academics and the armed services they populate ever since. In 1898, a gentle cadet named Oscar Booz was critically injured in West Point’s underground fight club. During a subsequent congressional inquiry, New York Rep. Edmund Driggs described the academy’s hazing culture as “detestable, disgraceful, dishonourable, [and] disreputable.”

Military schooling took off nevertheless during the early 20th century, with roughly 280 institutions opening in the United States between 1903 and 1926. The five academies operated by military branches, including West Point, were the elite. The rest—private, religiously chartered, or state-run—attracted a more eclectic student body, ranging from aspiring officers to troubled adolescents whose parents felt they could use some discipline. Enrollment peaked after World War II, but by the end of the Vietnam War, 65 percent of the institutions had closed their doors. Military schools increasingly became associated with discipline for kids with behavioral issues.

Valley Forge was founded in 1928 by Lt. General Milton Grafly Baker, a veteran of World War I and close confidant of West Point graduate Dwight D. Eisenhower. At the height of its enrollment in the late 1960s, Valley Forge had 1,169 cadets—most white and all male. By the time Navy Rear Admiral Peter Long took over as president in 2000, the Forge was down to a few hundred students and on the verge of bankruptcy.

A former provost of the Naval War College, Long focused, with some success, on improving academic programs, and he managed to get the school on steadier financial footing, thanks in part to a post-9/11 enrollment surge. But in November 2004, the board of trustees booted Long for an alleged pattern of sexually harassing employees. (Long sued the school, claiming the allegations were cooked up by a trustee who disapproved of his management style. The case was settled out of court.)

The Forge has since cycled through eight presidents. By many accounts, its trustees and administrators—mostly former military men—have downplayed the school’s problems by concocting positive images and suppressing scandals. To close budget gaps, they chopped haphazardly, deferring major maintenance projects, gutting academic programs, and laying off dedicated employees. A few years ago, the school began rationing toilet paper. It also relied on well-to-do foreign students, who pay higher tuition.

Cadets listen to Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney at a 2012 Valley Forge rally.

Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post/Getty

Students of color and female cadets were admitted, if not with open arms. In a 2007 racial discrimination lawsuit, Forge teacher Harold Price, chair of the foreign languages department, claimed the school wasn’t painting over racist graffiti—the suit cites one Black cadet who likened the campus atmosphere to a “race war.” Other sources told me racial slurs were common: “15-year-old white boys with silver spoons in their mouths saying the n-word. It was disgusting,” says a 2020 graduate.

Last August, a mother sued the Forge, alleging that Black cadets were punished far more harshly than others. Non-Black administrators collectively referred to Black cadets as “a gang,” the lawsuit claimed, and unruly non-Black cadets—one literally spat in the face of a staff member; another elicited a swat response by threatening to “blow up the school”—were allowed to remain on campus, while her kid was suspended over a racially charged fight he wasn’t even involved in. (In a response to the lawsuit, the school disputed her account of the incident.)

The decision to admit women into the junior college was made in 2005 by Long’s successor, Charles “Tony” McGeorge, the Forge’s first civilian president. The move evoked a vehement response from powerful alumni (including McGeorge’s son), who complained that Valley Forge was losing its character. And the female cadets were met with hostility. “The rumors were that we were all sluts, and that we were easy,” one of them told the local paper.

Therese Dougherty, who oversaw student activities and the school’s summer camp for McGeorge’s successors, filed a gender discrimination lawsuit in 2013 contending that administrators treated her in a “condescending and demeaning manner” and showed favoritism toward male employees. In an internal 2019 survey I obtained, cadets complained about inadequate physical security. The school “doesn’t want to deal with sexual harassment,” a female cadet wrote, and students guilty of sexual misconduct saw their behaviors “pushed under the rug.”

Another former cadet who attended around the same time told me she was drugged at an off-campus party and then sexually assaulted by a male Forge cadet while unconscious. She shared her story with several friends at the time (I spoke with two who confirmed this), one of whom proceeded to “beat the shit out of” the guy. When the TACs started asking questions and she gave them her account, “one of them said it was my fault.” The alleged assailant was allowed to remain on campus for the semester. “People could do whatever they wanted,” the young woman told me. “Rules weren’t being enforced.”

“I felt unsafe,” she added.

The most comprehensive account of abuses at Valley Forge came in 2015, when Robert Wood, the school’s Title IX officer, filed an explosive whistleblower complaint alleging that child abuse and sexual misconduct cases had been mishandled. The still-pending complaint warns of a “propensity” among TACs “for cadet allegations to be covered up and interfered with.” Wood also alleges that his attempts to investigate claims were repeatedly met with implicit threats by top officials, including William Gallagher, a retired Army colonel who held various senior roles.

In a contemporaneous memo to the Department of Education, Wood wrote that his efforts to investigate a sexual assault complaint involving two male cadets were impeded by Gallagher, who demanded Wood “cease” his work. During another standoff, Gallagher emailed an HR official asking when Wood’s contract was up for renewal. This prompted the school’s lawyer to warn that firing him would amount to a “retaliatory discharge” based on Wood’s efforts to uncover “serious breakdowns” in how abuse allegations were dealt with.

Wood quit the Forge that year, in any case, after seven years on the job. But by the accounts of some cadets, their situation hasn’t improved. Based on the school’s own data, Valley Forge logged at least 30 incidents of alleged sexual misconduct from 2015 through 2020, from stalking and fondling to rape; two ongoing lawsuits claim the school has attempted to impede investigations by its Title IX office. Wood also alleged that middle and high school students were left unattended at night, which he described as “indefensible.”

Other sources back that up. In 2018, one former TAC said he was tasked with a night shift overseeing “four buildings, or 300 kids” by himself. The TACs were willfully “inattentive” to misbehavior, a 2021 graduate said. “There are many fights—I mean many, many fights I have seen that played out completely,” he added, “where one student was beaten to a bloody fucking pulp before anyone intervened.” (In December, the Valley Forge Sucks Instagram posted a video of two young cadets in camouflage freely pummeling one another in a bathroom.) Supervising officers got burned out, Schumacher told me, and began ignoring even blatant misbehavior: “They’d shut their door to the TAC office.”

While many secondary schools grapple with some amount of egregious behavior, the military model made for a more challenging environment. “When a structure is set up on rank, power, and pain, you’re going to have problems,” a former Forge official explained. Wood’s complaint cites parental concerns about supervision and abuse dating as far back as 1997. In 2004, a 17-year-old cadet was charged with stalking, “involuntary deviate intercourse”—a category of felony crimes ranging from forced oral and anal sex to other forced nonvaginal penetration—and sexual assault against a fellow student, prompting two other cadets to come forward with related allegations against him. This led to further charges, including assault and “terroristic threats.” (According to a local news report, a juvenile judge ultimately convicted the assailant of three lesser counts, and sentenced him to home detention.)

In 2007, two parents told the Philadelphia Inquirer they were pulling their sons from the Forge after one of them, age 16, was brutally beaten by peers, and the other, a 13-year-old, was “repeatedly tormented,” kicked while doing pushups, and branded with a five-pointed star. In 2017, a 16-year-old cadet was allegedly subjected to a sadistic hazing ritual called “tooth-pasting.” The now-former cadet alleges in a lawsuit that fellow cadets hit him with a lacrosse stick, pushed it down his throat, and then tried to shove it into his anus. He was also waterboarded, he claims, and had his head slammed into a wall. The same suit claims that after a 13-year-old classmate reported his own abuse to school officials, his tormentors branded him with a “B”—for “bitch.”

Based on the school’s nonprofit tax filings, Valley Forge has spent more than $4 million on legal fees over the last two decades. Perhaps the school’s most formidable foe these days is Stewart Ryan, the Philadelphia-based lawyer who prosecuted Bill Cosby. He now represents the former cadet who filed the tooth-pasting lawsuit, and three others who allege that, as minors, they, too, experienced tooth-pasting and other abuse at the Forge from 2014 to 2018. Additional clients, Ryan says, are preparing complaints that stem from the Forge’s “intentional ignorance.”

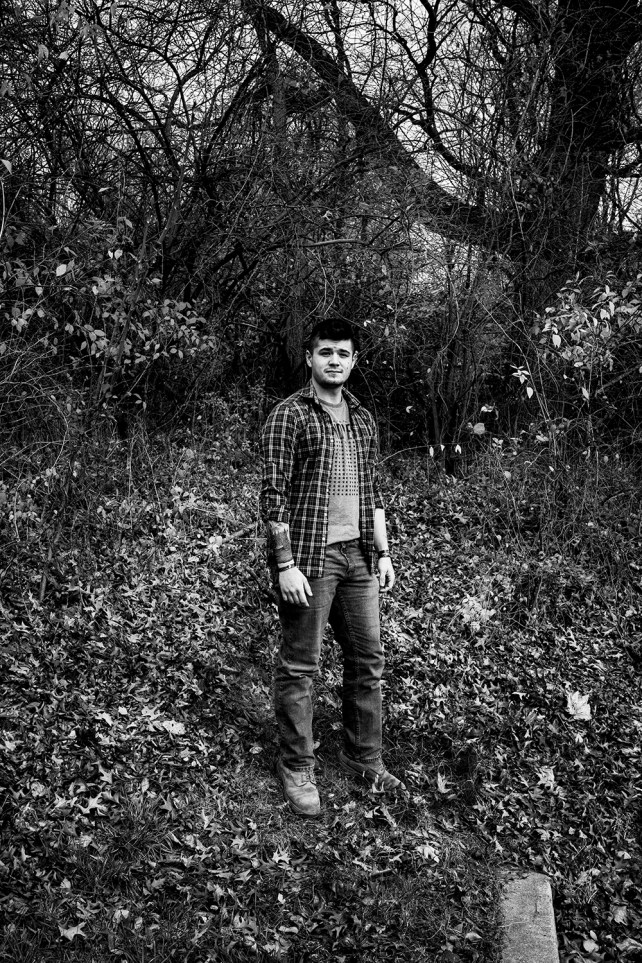

Ryan Niessner, who submitted a sworn affidavit for one of Stewart Ryan’s cases, told me he was sexually assaulted as a 15-year-old Forge cadet in 2009. As he returned from the shower one night, a door flung open and five cadets dragged him into a room and attempted to penetrate him, first with fingers, then a coat hanger: “I struggled for a little bit, but five, six other people—numbers just kinda won that.” Soon after, he fought off another tooth-pasting attempt. He became withdrawn and depressed, and would eventually require therapy. In junior college, hoping to thwart such attacks, he and some of his Forge classmates took on overnight surveillance shifts. “We were the only adults in the building with high schoolers and middle schoolers,” he recalls.

Ryan Niessner

Devin Oktar Yalkin

In his affidavit, Niessner testified that when he reported his abuse to the TAC office, an officer asked, “Will your parents sue?” (They did not.) “After this meeting,” he wrote, “I was discouraged from reporting this incident to anyone else.” A few years later, he shared his story with the police, who spoke to school officials. Niessner doesn’t know how the Forge responded. But when a former administrator reported a different tooth-pasting attack to her superiors, “they didn’t do anything about it,” she said. Bossert told me that some of the dozen or so cadets thought to have participated in tooth-pasting assaults were dismissed, only to return the following semester. None of them tried it again, to his knowledge. “But think of the type of kids that would do that,” Bossert says. “They are going to do hell across the board.”

In another troubling case that Wood discussed with a local newspaper in 2017, four male college cadets conspired with a fifth to covertly film his sexual encounter with a drunk female cadet. A disciplinary board advised that all of the perpetrators be dismissed, but the school’s president ignored the recommendation and allowed three of the five to stay. As punishment, they were ordered to paint the commandant’s house. One of the boys spoke at graduation, and “the young lady who had been assaulted had to sit there and listen,” Wood said.

When a former TAC raised concerns about Symantha Hicks—a Forge guidance counselor who, according to police records, was suspected of giving alcohol to minors and performing oral sex on a 16-year-old—a school official allegedly tried to convince him not to go to the cops. Hicks denied engaging in sex with the boy, but was convicted of “corruption of minors.” The Forge had hired her to replace another female counselor whose comportment with students came under scrutiny. But when an administrator raised concerns with the HR office about that counselor—who was later convicted of sexually assaulting a 15-year-old at another school—“I was told that it was none of my business, to just stay out of it.”

Valley Forge also briefly employed a former soldier named Steve Stefanowicz as a TAC overseeing middle and high schoolers, until staffers discovered he’d been a key player in the Abu Ghraib torture scandal.

Walt Lord’s appointment as president in 2018 heralded a brief period of reform at Valley Forge. The son of working-class parents, Lord grew up in an Irish Catholic neighborhood in South Philadelphia. He received a full ride as a Forge cadet in the 1980s, and even got married in the school chapel. He ascended through the Army ranks to the position of major general and served in Sarajevo and Afghanistan.

Square-jawed and warm, Lord believed the only way to save his alma mater was by listening to people’s concerns. He met frequently with students and staff, snapped selfies with cadets, and cultivated closer relations with alumni and parents. He focused on positive reinforcement, using military challenge coins to reward good behavior. Lord also provided intense guidance to misbehaving cadets and booted a handful whose behavior had become threatening. “He didn’t just kick somebody out,” a former trustee told me. “He had a valid investigation into what the issue was, and the punishment fit the crime.” This new approach quickly netted the school dozens of new students.

Yet Lord felt micromanaged by the trustees, including board chair John English, who served briefly in the Marines before founding a consulting firm. English demanded a say in day-to-day decisions but neglected systemic issues, according to the former trustee, who adds that most board members were disengaged: “Everyone told war stories. We didn’t get anything done.”

Former Valley Forge president Walt Lord presided over a brief period of reform before stepping down.

Devin Oktar Yalkin

These concerns were echoed in an audit undertaken on behalf of a board member by the Healey Education Foundation, which warned that “Valley Forge is not going to survive by looking backwards.” A draft report, leaked to the press in 2019 and cited in a lawsuit that was later dismissed, noted that enrollment had declined 40 percent in the previous five years, and the school was nearly $7 million in debt. The authors laid most of the blame on the trustees’ hasty “Ready, Fire, Aim” decision-making style.

Lord felt confident he could tackle the Forge’s cultural issues. He also arranged weekly meetings with Vince Vuono, the chief financial officer, to get a better handle on the money woes. But Vuono would provide only the most basic, generic information: “My biggest point of frustration was the fact that I couldn’t get the CFO to open up and tell me exactly where we stood financially,” Lord told me. “It was the most bizarre thing in the world.” Other administrators were similarly perplexed. “Nobody knew where the money was going,” one recalled.

Lord and others alluded to a multimillion-dollar donation from the family of an alum, the son of Ettore Boiardi, a.k.a. Chef Boyardee, which they believed was intended for building upgrades that were never completed. (The Forge has previously denied that the funds were misdirected.) The school is now being monitored by the US Department of Education for “financial or federal compliance issues,” which may stem, at least in part, from its sloppy handling of Pell grants. The Forge wasn’t adequately communicating with students about the Pell program, and multiple cadets said they never received money they were promised. “I never really felt like they were following financial aid procedures,” one former staffer recalled.

Lord resigned in March 2019, after less than a year on the job, citing the board’s incompetence. Trustee Jessica Wright, the former head of Pennsylvania’s National Guard, announced her resignation shortly thereafter in a scathing letter that inveighed against the board’s “reprehensible” apathy toward the school’s challenges. As the news swept the campus, cadets showed up at Lord’s living quarters with cake, cookies, and a teddy bear.

Days later, hundreds of alumni arrived from around the country for a tense meeting with school officials at Mellon Hall, a stately building with a checkerboard-tiled ballroom. Nearly 4,000 parents and alumni signed a petition imploring the board of trustees to work out their differences with Lord so that he could be reinstated. Instead, school officials blacklisted their most vocal critics, Lord included. “We wanted to open up dialogue and fix the school,” said Scott Newell, an alum and parent of a former cadet. “What we got was silence. Parents were blocked on social media, concerns were ignored, and ultimately [certain] alumni were barred from the campus.”

Less than a month after Lord’s departure, a Forge cadet was assaulted and hospitalized. The local ABC News affiliate reported he’d been “mistakenly targeted as ratting out a group of cadets for underage drinking.” Thus began the latest phase of what the Inquirer called a battle for Valley Forge’s soul. Lines were drawn. On one side were concerned parents and alumni, and Lord; on the other an increasingly bellicose group of trustees and administrators, including Lord’s replacement, current president Stuart Helgeson. “We keep hoping these guys would go away,” Helgeson complained to the newspaper. “They’re weakening the brand.”

Helgeson addressed the budget shortfalls by slashing college sports programs and eliminating the 16-horse cavalry. A prime slice of campus was sold off to developers for $1.6 million. Helgeson also tried some new revenue streams, such as licensing the Valley Forge name to a K–12 school in Qatar and submitting a proposal to the local school board to establish a public charter school on the grounds. (The board rejected the plan, citing trustees’ dearth of educational experience and a lack of competent curriculum guidelines, and accused the Forge of trying “to subsidize its private school with taxpayer dollars.”) Finally, in a decision the cadets would feel acutely, Helgeson promoted TAC J.J. Rivera, a fellow Marine, to the title of commandant.

At least five cadets I interviewed identified Rivera, a former helicopter pilot who didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, as one of the most abusive TACs. Bossert and another former TAC told me Rivera sometimes slow-walked investigations—including one that involved a rape.

As Rivera’s former supervisor, Bossert recalls cautioning him about his demeanor with the young women on campus. One former administrator went so far as to call him a “creepo,” noting that female cadets often complained to her about Rivera’s behavior. Two female former cadets recalled to me how, after they were caught trying to sneak off campus, Rivera threatened to look in on their rooms at night when they slept.

Another one recalls Rivera flirting with her repeatedly and saying she reminded him of his wife. That cadet said Rivera once made her remove a shirt that violated the dress code—she had to extract the garment from underneath her sweatshirt: “He was right there, watching me.” A male former cadet told me that Rivera—after learning he’d drilled with an ROTC unit at a base where Rivera also had trained—advised the boy, then still a minor, to check out a nearby strip bar called Club Risqué. (Two of the cadet’s former classmates confirmed that he told them this story shortly afterward.)

In 2020, fed up, Schumacher and a dozen or so other cadets created a PowerPoint and presented it to school officials. Titled “State of the Forge,” it detailed squalid living conditions, flawed Covid-19 policies, and ongoing bullying, including an attempted “lynching”—in which Black cadets offended by a white student’s racism allegedly tried to choke the kid with a belt. The presentation claimed that five classmates had either tried to kill themselves or had spoken to leadership about doing so that school year. The cadets I interviewed, along with an internal list of student grievances I obtained, say the Forge frequently minimizes mental health issues, with a school nurse once scolding a student for “sending up red flags that don’t need to be sent up.”

Another slide depicted Rivera as particularly abusive, a contention bolstered by numerous staffers and cadets, including one who remembers Rivera routinely ordering Schumacher into his office just to scream at him. Rivera was “well-contained” during the presentation, Schumacher said, but their effort to speak truth to power amounted to naught. “It was a ‘brush off the shoulder’ kind of thing,” he said.

From the early West Point scandals to recent reports of hazing at the Virginia Military Institute, abuses at military schools have been codified in American culture through media reports, literature, and Hollywood tropes. Taps, a 1981 movie filmed at the Forge, follows a group of cadets who rebel violently against the proposed closing of their fictional academy. By the accounts of those I spoke with, the Forge has indeed come to mirror many of the worst aspects of military culture—the lies and cover-ups, the unwillingness to deal appropriately with sexual assaults, and the lack of financial transparency. The word “snafu” comes from a military acronym meaning “situation normal: all fucked up.” And that’s a sentiment the Forge and like-minded institutions seem to be imprinting upon the next generation of military leaders.

The deliberately punitive ethos of military schools rests on the false assumption that it wrings out bad habits and encourages good ones. But Michael Karson, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of Denver who specializes in child abuse, told me that one of the few hard laws in his field is as follows: “Punishment doesn’t work” to change people’s character, he says. It merely “makes them obedient.” This truth helps highlight the moral clarity of dissenters such as Salinger and Schumacher, whose insubordination was a clear-eyed response to abuse, a righteous rejection of bullying masquerading as command and control.

One can reasonably argue that the military must instill compliance and cohesion in its combat units. But the kind of torment Valley Forge kids were subjected to, trauma that can leave psychological wounds as deep as those borne by soldiers on a battlefield, is impossible to justify. Numerous parents have spoken of the ways, large and small, that their children were scarred by the Forge, and many former cadets, Schumacher included, have sought therapy to process their experiences. One mother told me that ever since her boy was raped at Valley Forge, a trauma incurred many years ago, he sleeps with a hunting knife under his pillow. And then there was the 18-year-old cadet who never made it to graduation.

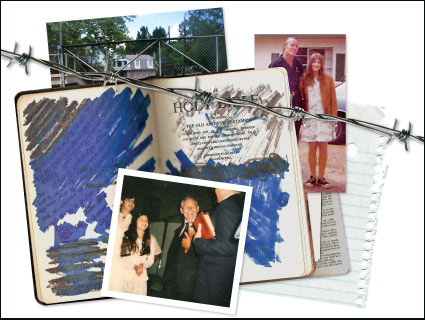

Even the famously reclusive Salinger would eventually open up about his ambivalence toward the Forge. In an unpublished 1995 letter to a friend and former classmate, shared with me by the J.D. Salinger Literary Trust, the author, then 76, seemed to regret the untitled three-stanza poem he wrote shortly before graduation, which was placed on display in the school chapel after Salinger got famous. It begins:

Hide not thy tears on this last day—

Your sorrow has no shame;

To march no more midst lines of gray;

No longer play the game.

“I’ve planned for years to stop by and either tear the exhibit down or at the very least add a little obscene graffiti at the bottom,” Salinger wrote. He reflected, too, on the “interesting collection of misfits” he’d befriended at the Forge, and the memories they shared, bad and good.

But it was escaping the campus that brought him the greatest joy: “Though [the Forge], to me, was on the whole a thoroughly bad joke, its pretenses and posturing irreversibly sham, contemptible,” Salinger wrote, “I wonder if I ever again felt as free, as gratefully on the loose, as I did on that pretty walk to Wayne and the diner on a Sunday after signing out.”