Editor’s note, May 7, 2023: This essay was published three days after the gun massacre at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. In the nearly one year since, we’ve had to update our mass shootings database 15 additional times, including with Saturday’s mass shooting at a shopping mall in Allen, Texas.

For many years now, every horrific gun massacre has ricocheted widely with a familiar theme of outrage and surrender. On May 25, the day after a heavily armed, suicidal 18-year-old murdered 19 children and two adults at a Texas elementary school, Washington Post columnist Brian Broome published one of the more powerful versions of that narrative I’ve ever read. “Nothing happened after innocent children were slaughtered the last time, or the time before that, and nothing is going to be done now,” he wrote, citing Columbine, Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook and Parkland.

Broome’s column articulated the enduring shame of our nation’s political stalemate and pathetic inaction on gun policy. It was piercing and poignant—and, in my view, wrong.

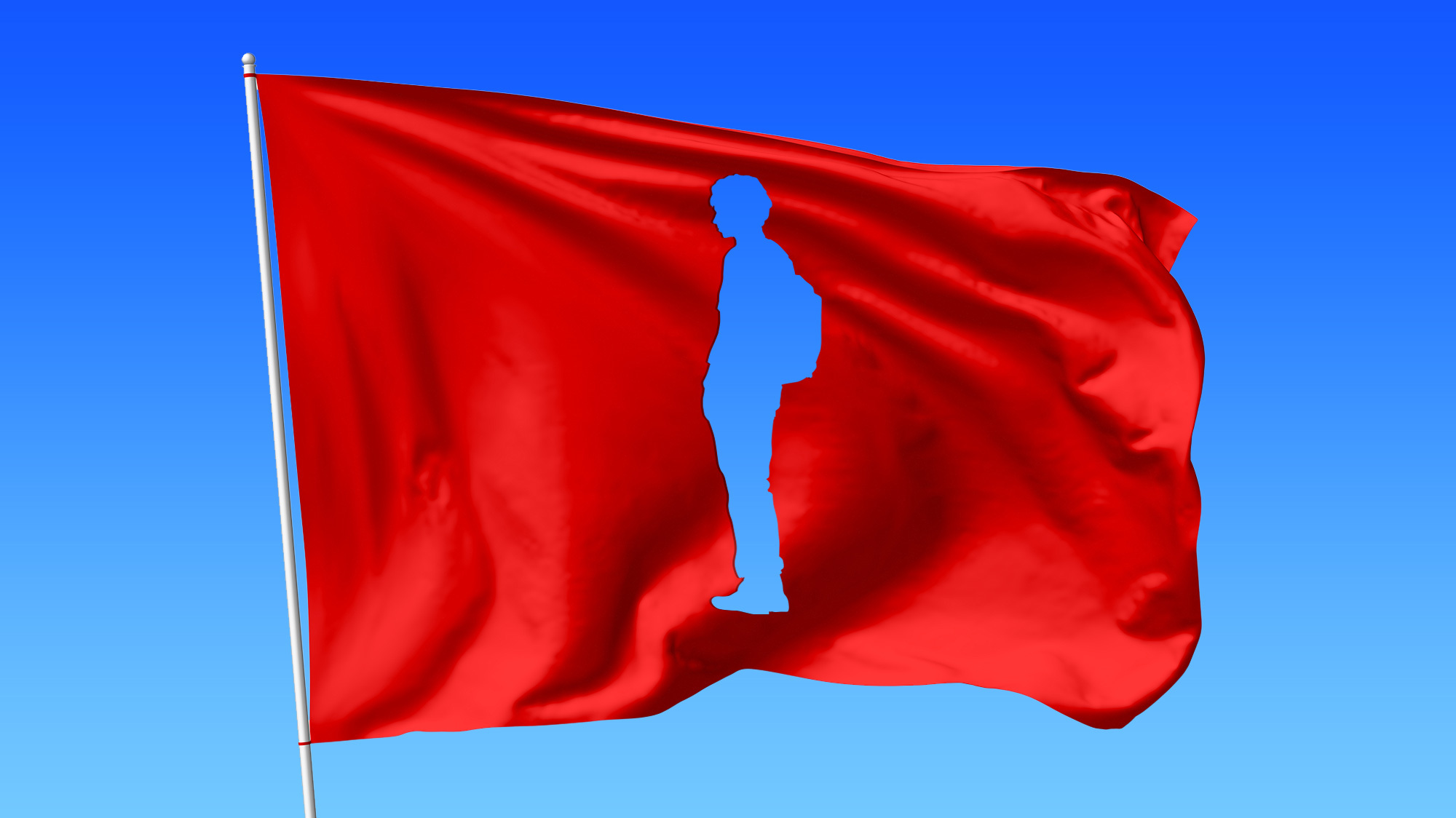

It’s not just that we shouldn’t resign ourselves in perpetuity to such outrage, rightful as it is. This narrative has become part of the problem itself—in some cases possibly even fueling the escalating cycle of mass shootings. That’s because it validates the recurring violence, framing it as an indefinite feature of our reality.

And mass shooters pay heed. After nearly a decade of studying these attacks and how to prevent them through the work of behavioral threat assessment, I documented extensive case evidence for my book, Trigger Points. The research shows that many perpetrators are keenly aware of media and political narratives about their actions.

They hope the public will focus on sensational coverage of their rage-filled “manifestos,” their sinister photos uploaded to social media, their ghastly livestreams. They want notoriety, and they seek justification and credibility for their acts of violence. And in the message that America will never stop these mass shootings, they find such affirmation.

“School shootings happen all the time,” remarked a troubled 17-year-old subject of one threat investigation I examined. He had become fixated on watching videos about the 2018 school massacre in Parkland, researched where he might buy a firearm, and later commented that committing such an attack could be an easy way for him to “get famous.”

The mass shooter driven by racist hatred in Buffalo, New York, cited livestreamed footage and writings posted online from a 2019 massacre as a source of inspiration, detailing his own plan to do the same, “to increase coverage and spread my beliefs.”

Mass shootings can be prevented. In fact, it happens with regularity at the hands of threat assessment teams. They work to intervene constructively with troubled people, often after someone in the orbit of those people becomes worried by their behavior and reaches out for help. The method relies to a great extent on community awareness—and its potential could grow if we do away with some big enduring myths about mass shootings.

One is that mental illness is fundamentally to blame for these massacres. After the horror at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde this week, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott pushed that argument in his public comments. Pro-gun politicians and leaders of the NRA have long used it as a tactic for distracting from the national debate over gun laws—essentially dismissing each new mass shooting as an inexplicable “evil,” as Abbott described it, and implying that responsibility for change lies squarely with the mental health field. (Never mind that Abbott just cut $211 million in April from state mental health services.)

No mass shooter, by definition, is mentally healthy. These are people with deep rage, despair and other problems, who need help in various ways. But the exploitation of mental illness in lay terms is highly misleading and counterproductive to preventing these attacks, as I wrote after the massacre in Buffalo:

The claim that mental illness produces such attacks implies that mass shooters are insane, as if they are disconnected from reality and act based on no rational thinking. This goes hand in hand with the common theme that these offenders “snap,” which suggests they commit impulsive acts of violence, bursting forth from nowhere. Both explanations are wrong.

Extensive case history shows that mass shooters don’t just suddenly break—they decide. They develop violent ideas that stem from entrenched grievances, rage, and despair. In many cases they feel justified in their actions and regard killing as the sole solution to a problem. They arm themselves and prepare to attack, choosing where and when to strike. Often this is a highly organized and methodical process.

Blaming mental illness for mass shootings inflicts a damaging stigma on the millions of people who suffer from clinical afflictions, the vast majority of whom are not violent. Extensive research shows the link between mental illness and violent behavior is small and not useful for predicting violent acts; people with diagnosable conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are in fact far more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence.

Another major falsehood is continually reinforced through news reporting that quotes people who knew or came in contact with a shooter: “I never thought he could do something like this,” and, “No one could’ve seen this coming.” In many cases, nothing could be further from the truth. In the scores of threat investigations and mass shootings I studied, every case subject showed a mix of identifiable warning signs. These fall into eight areas:

Entrenched grievances: Shooters often stew over mistreatment or injustices, real or perceived.

Threatening communications: Signs of intent, or “leakage,” can be veiled or direct, noticeable in talk, writing or online posts.

Patterns of aggression: Acts such as domestic violence indicate a capacity to harm and correlate with risk.

Stalking behavior: Fixation and harassment are red flags that were first studied in political assassins and celebrity stalkers.

Emulation: This is the so-called copycat problem; mass shooters often signal that they identify with past attackers.

Personal deterioration: Breakdowns of routine and loss of resilience point to tendencies that can culminate in a murder-suicide.

Triggering events: A major failure in school, work or a relationship can set in motion plans for violence.

Attack preparation: Acquiring a gun, practicing at a range and surveilling a venue are common in the days or weeks before an attack.

Many of these warning signs, we now know, were present and escalating long before Tuesday’s nightmare in Uvalde—as they were before the one in Buffalo, and before that, in the run-up to the massacre at Oxford High School in Michigan.

This is the true nature of these attacks. And the expanding knowledge of these patterns represents opportunity for threat assessment teams to intervene, before it’s too late.

Diminishing this American nightmare is going to take many different forms of action: continuing a relentless, long-term effort to strengthen our nation’s gun laws. Quashing a surge in violent political extremism. Investing in a lacking mental health care system. And building community-based violence prevention programs.

In a society with 400 million firearms and where firearms are often easy to obtain, even all that may only be a start. But it will be a powerful rebuttal to the nihilism that mass shooters feed on—and to the hopelessness about this epidemic that so many Americans once again feel.