Mother Jones illustration; Getty

The Inflation Reduction Act—the blockbuster tax and climate reform bill passed by the Senate earlier this week—includes several provisions aimed at forcing corporations to pay a fairer share of their taxes. These include a rule requiring large corporations to pay a minimum of 15 percent of their profits in taxes, $80 billion in additional funding for the IRS to ramp up tax enforcement, and an extension of the 2017 tax bill’s limits on the use of business losses to shrink tax bills.

But there’s another change worth diving deeper into. If passed, the IRA will impose a 1 percent tax on stock buybacks, a tactic used by corporations to increase their stock price. Buybacks continue to grow in popularity: In 2022, corporate America is projected to spend a record $1 trillion on them. They’ve long caused consternation among Democrats, who accuse corporate executives of using buybacks to avoid taxes and to enrich themselves instead of better compensating their employees: a “sugar high for corporations” and a “tax scam to reward CEOs while laying off workers,” in the words of Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

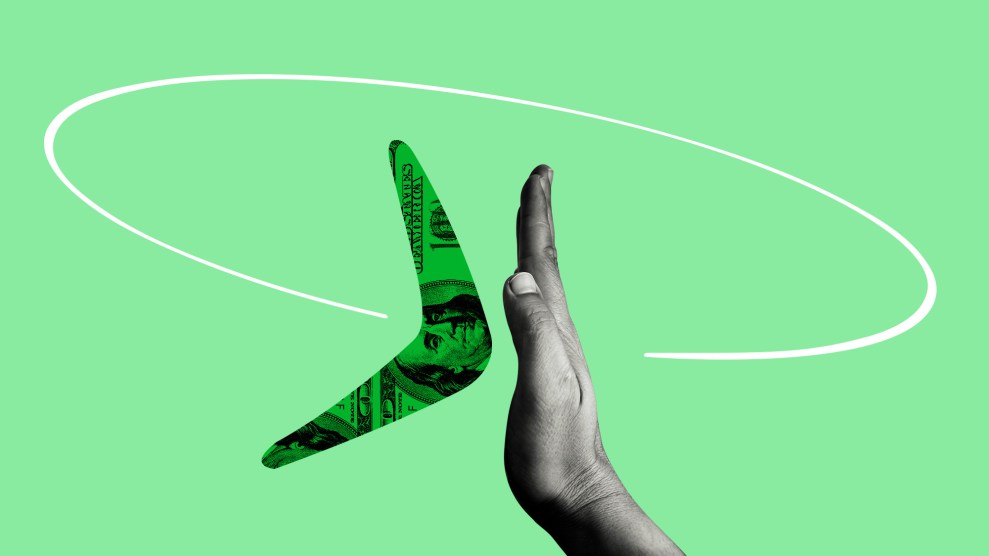

To understand why Warren and other Democrats have targeted buybacks, it’s helpful to first dig into how they work, and why corporations love them. A buyback is when companies purchase shares of their own company from investors, driving up the value of the remaining stock because there are fewer shares circulating. Buybacks are taxed at the lower capital gains rate, which maxes out at 20 percent for the wealthiest households. But for those investors who don’t sell their shares back to the company, there’s no tax—even though the value of their holdings has increased. Until that investor sells the asset, their wealth will grow tax-free. And thanks in part to a tax code loophole that enables the wealthy to pass shares on to their heirs, who can then skip paying capital gains taxes on them altogether, buybacks play a role in building untaxed generational wealth.

This tax dodge is at the root of what has made buybacks so popular. Illegal until the early 1980s, buybacks have skyrocketed in the last five years thanks to the Trump administration’s 2017 tax bill. The law heavily reduced corporate taxation, so many companies started investing their extra tax savings into buybacks—enriching their top executives and their investors, often at the expense of their workers. A report from the Brookings Institute in the spring found that 16 major American corporations that employ millions of frontline workers spent $49 billion on buybacks during the pandemic, and less than half of that to increase worker wages. The companies “could have raised the annual pay of their median workers by an average of 40% if they had redirected the stock buybacks from the last four quarters to workers,” wrote the authors of the report.

That’s what drove Sens. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) to propose this buyback tax. “Instead of spending billions buying back stocks and handing out CEO bonuses, it’s past time Wall Street paid its fair share and reinvested more of that capital into the workers and communities who make those profits possible,” Brown said in a statement when first proposing the tax.

Once the IRA is signed into law—it’s expected to pass the House as soon as Friday—companies will have to shave 1 percent off buybacks to send to Uncle Sam. But to what extent will this tax help the majority of Americans? Will it shrink the advantages that have made them a favored tactic of wealthy executives and investors, and who will see the benefits of that change?

The answer is complicated, but two impacts of this change are important to note. The 1 percent tax will raise about $73 billion in tax revenue for the federal government over the next decade—more than five times the revenue that would have been raised from closing private equity’s favorite tax loophole (a provision cut from the final bill), and a third of the $223 billion that is projected to be raised from the 15 percent minimum tax on corporations. That is a lot of dough from just 1 percent. Aside from raising revenue, the buyback tax will mitigate the advantage for top executives, company founders, and foreign investors, while also encouraging big companies to reinvest in their workers to boost jobs and pay. And going from no tax to some tax is a meaningful first step toward more robust taxation in the future, says Daniel Hemel, a professor of tax law at New York University’s law school and the co-author of a 2021 paper about the benefits of imposing a tax on buybacks.

Confronted with the prospect of additional taxes, companies may issue fewer or smaller buybacks to compensate for the extra money they must send to the government, essentially passing the cost of the tax to their investors. And faced with smaller buybacks, firms that manage millions of dollars in investments and own enormous chunks of stock in major companies may start to favor buybacks less over dividends, which have fewer tax advantages.

“CEOs are basically taking orders from Blackrock, Vanguard, State Street, Fidelity, because those companies own a ton of stock in every publicly traded corporation,” Hemel says. “So hopefully, BlackRock and Vanguard really do pull the strings.”

Meanwhile, there are several other longstanding issues that Democrats hope a buyback tax will help counteract. The first is the use of buybacks to juice CEO pay while shrinking corporate taxes. Thanks to legislation passed in the ’90s, companies can compensate their top executives with stock and then deduct its value from their end-of-year tax bill. That means corporations have used buybacks to drive up their share prices and later boost their executives’ pay—and then deduct the grand total from the company’s taxes.

Then there’s what Hemel and his co-author Gregg Polsky, a professor at University of Georgia’s law school, have deemed the “Panama Papers problem.” Foreigners who stash their wealth in offshore havens like Switzerland or the Cayman Islands often invest that offshore money in the US market. If their shares get dividends, they must pay an even higher tax rate on those than Americans—up to 30 percent. But capital gains are taxed by the country where the funds are located—meaning that, in the case of buybacks on investments stored offshore, they simply won’t get taxed at all. By creating a tax to make buybacks less attractive to corporations, Congress is mitigating a popular gambit for foreign tax dodgers. And potentially also raising some serious cash: Hemel and Polsky calculate that if the buyback tax were to rise to 2.5 percent, it would raise about $27 billion from foreign investors in tax havens.

Finally, Hemel and Polsky’s “Mark Zuckerberg problem” points to yet another tax advantage of buybacks. Named after the Facebook CEO, it refers to founders who get early equity in their startups. Those stakes grow to enormous valuations, which can be even further juiced through buybacks. If those founders hold on to those shares and pass them on after death, that next generation can cash them out without paying any taxes, thanks to the aforementioned tax loophole for heirs.

A 1 percent buyback tax certainly won’t make all of these advantages disappear. But it will mitigate them, and it will kick off an incremental approach that has worked in the past to reform tax policies. The first federal income tax in 1863, Hemel points out, was just 2 percent, and was then built up over the last century into the robust income tax system used today.

“Part of what made the 1 percent excise tax on buybacks possible was that it was only 1 percent,” he says. “But part of what makes the 1 percent tax attractive to progressives is the fact that it can become something other than 1 percent.”