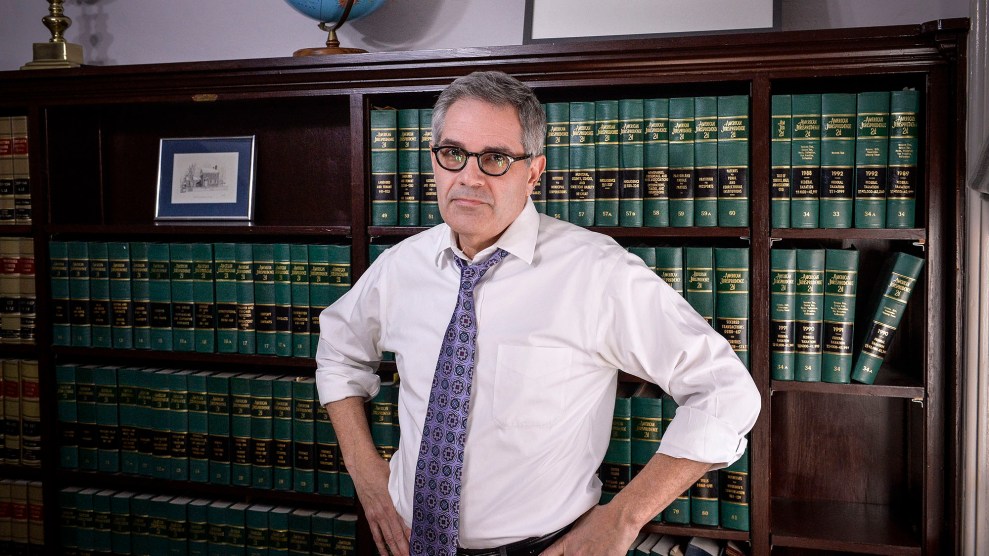

District Attorney Larry Krasner at a news conference in January Matt Rourke, File/AP

Republican lawmakers in Pennsylvania are trying to impeach Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, a reformist prosecutor who built a national reputation for attempting to curb mass incarceration and hold violent cops accountable, and who was overwhelmingly reelected last year to a second term.

Impeachment proceedings often follow allegations of criminal behavior or corruption, but Krasner isn’t accused of either. Instead, Republicans claim that his progressive policies—like requesting to jail fewer people before trial and letting certain low-level offenders off the hook—led to record-breaking gun homicides in Philadelphia. “I recognize the unprecedented nature of what must be done and am confident our members are up to the task,” Republican state Rep. Martina White told reporters on Wednesday while announcing the articles of impeachment. In Pennsylvania’s entire history, only two state officials have been impeached.

The crusade against Krasner is part of a broader, nationwide push, led largely by conservatives amid fears about crime rates, to remove progressive district attorneys from office or limit their power. In Pennsylvania and elsewhere, however, the best available crime data does not support allegations that these prosecutors are responsible for the recent uptick in shootings. In fact, at least a couple of studies suggest that violence has risen less rapidly in their jurisdictions than in other places led by more traditional prosecutors with tough-on-crime policies.

Krasner took office in 2018 and soon announced a series of bold reforms. Chief among them, his office would no longer pursue charges against sex workers and individuals caught with marijuana possession, and no longer request cash bail from people accused of some misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. He instructed his team to prioritize diversion programs and seek shorter prison sentences than his predecessors had sought, and he helped exonerate more than two dozen people who were wrongfully convicted under previous district attorneys. He also sued pharmaceutical companies for labor practices that fueled the opioid epidemic, and created a list of police officers who lied on duty, used excessive force, racially profiled, or violated civil rights.

He quickly came under attack by politicians who blamed him for gun violence: Nationally, homicides rose about 30 percent during the first year of the pandemic, mostly from shootings, and Philadelphia saw a record 562 killings in 2021, compared with 356 in 2019. Though Krasner has prioritized violence prevention efforts, his critics, including Philadelphia Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw, accuse him of letting too many criminals out of jail and convicting fewer people for gun possession. But leading criminologists do not believe his policies were responsible for the rise in murders. University of Oxford professor Christopher Stone, for example, recently examined violent crime rates in Philadelphia and other cities with progressive prosecutors, including Brooklyn, Chicago, and St. Louis. “Not only had violent crime not risen more under progressive prosecutors than under the old guard [of traditional prosecutors],” he wrote in January, “but in every place I looked the progressive prosecutors were presiding over greater reductions or smaller increases in violent crime than in their surrounding counties.”

Another study by academic researchers at several major universities, including the University of Toronto, the University of Missouri at St. Louis, and Boston University, drew similar conclusions. The researchers found that from 2015 to 2019, murder rates rose in fewer cities with progressive prosecutors (56 percent) than cities with traditional prosecutors (68 percent). And when gun killings spiked nationally from 2020 to 2021, the increase in violence was slightly less in places with progressive prosecutors than elsewhere. Plus, there was no meaningful difference in robbery or larceny rates regardless of which type of district attorney was in charge.

“I think it’s really important to emphasize the extent to which we looked for a relationship [between a prosecutor’s progressive policies and crime rates] and found none,” Todd Foglesong, a fellow in residence at the University of Toronto and one of the study’s co-authors, told the Atlantic. (Fordham University professor John Pfaff, who examined homicide rates in 69 cities in 2020, reported similar findings.)

Other researchers agree. As I reported in May, three economics and politics scholars from Texas A&M University, Rutgers University, and NYU examined 35 urban districts around the country and found that crime rates did not increase in places where DAs implemented progressive reforms like pursuing less pretrial detention, more diversion from jail, and less prosecution of minor offenses. In a more focused study of the Boston area, the researchers found that defendants whose misdemeanor cases were dismissed by lenient prosecutors were 58 percent less likely to be arrested later for another crime than defendants who were charged by stricter prosecutors for the same original offense. One possible reason is that prosecuting people disrupts their lives, forcing them to take time off work for hearings and contributing to mental distress, co-author Jennifer Doleac, an associate professor of economics at Texas A&M, told me. And for those who are convicted, a criminal record might make it harder to find employment or housing. “In short, the best evidence so far…implies that progressive prosecutors’ reforms are not the cause of rising homicide and shooting rates,” Doleac wrote of her research. “[T]heir current policies do not appear to be doing any harm—and in some cases appear to be doing substantial good.”

Pennsylvania lawmakers trying to impeach Krasner seem to be ignoring this wealth of data. Instead, they are justifying their attacks on him by pointing to a disputed study written by a former Republican district attorney, Thomas Hogan, who served two terms as a tough-on-crime prosecutor in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Hogan, now an adjunct fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, a think tank, wrote for the journal Criminology & Public Policy that Krasner’s policy of “de-prosecution” was “associated with a statistically significant increase” in murders in Philadelphia compared with previous district attorneys there. Several researchers who study criminology, sociology, and economics criticized Hogan’s methodology and accused him of making factual errors, allegations that he denied. A spokesperson for the journal emphasized that all its articles are peer-reviewed.

In September, three scholars from Princeton and Georgetown argued that Hogan’s study contained “fatal flaws” and should not be used to inform criminal justice policy; when the scholars corrected the issues they perceived in Hogan’s work, they wrote in their own paper, they found “no effect of de-prosecution on homicide.” According to Intercept reporter Akela Lacy, these scholars asked Hogan to share his data with them, but he did not reply. The scholars submitted their critique of his work to the same Criminology & Public Policy journal, but the journal rejected it; an editor stated, in an email to Texas A&M’s Doleac, that Hogan’s paper generated so much “buzz” that a single commentary about it would not suffice, and that the journal instead planned to host a public webinar and possibly later publish an entire special issue related to the subject of progressive prosecutors.

“The flaws in the paper were apparent pretty quickly, to anyone with access to the data & familiarity with causal inference methods,” Doleac wrote in a Twitter thread about Hogan’s study. (Hogan declined to comment to Mother Jones but pointed to his prior public statements, including a Substack article, in which he defended his research and argued that critics of his paper were making “obvious errors” in their analysis.)

If Krasner’s policies are so harmful to victims of crime, then why, in 2021, did he do best where SHOOTING CRIMES WERE THE GREATEST?

If you listen to the victims—actually listen, not just use them as a prop—they were pretty damn clear in 2021. https://t.co/zxN4pUOlgH pic.twitter.com/FY2yrpHy8q

— John Pfaff (@JohnFPfaff) October 25, 2022

As Republicans continue to claim that progressives like Krasner caused shootings to spike, it’s worth emphasizing that gun homicides rose just about everywhere in the United States during the early pandemic, from red states to blue, from rural towns to big cities, regardless of who was in charge. Leading scholars agree that prosecutorial policies were likely not responsible for the change in murders, and point to other trends and factors that may have been. There was the uptick in people struggling with unemployment and mental health problems during 2020, along with soaring gun sales.

Whether voters in a given area lean Republican might also play a role: A study by Third Way, a centrist Democratic think tank, found that murder rates in 2020 were a whopping 40 percent higher on average in the 25 states that voted for Donald Trump in the last election compared with states that voted for President Biden. In fact, 8 of the 10 states with the highest murder rates voted Republican in every presidential election this century.

In Pennsylvania, lawmakers hoping to address Philadelphia’s murder crisis could also consider another plausible factor: the cops. The Philadelphia Police Department was recently audited by City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart, who found that officers were doing a horrible job solving crimes, with the lowest homicide clearance rate among the country’s 10 largest cities from 2016 to 2020. As the Philadelphia Inquirer summed up, the audit offers “a damning picture” of a police department that “is inefficient, disorganized, backward, and wasting millions in taxpayers’ money.”

The state legislature also bears some responsibility for the violence: Gun-friendly lawmakers have repeatedly blocked Philadelphia’s attempts to pass stronger local gun control measures that might help reduce shootings.

All of which begs the question: Why are they pinning so much of the blame on Krasner?