Thomas Peipert/File/AP

At the 59 minute mark of [S]election Code—the Mike Lindell-produced documentary on Tina Peters, the Colorado election official who tried to prove that the 2020 election was stolen—there’s a three shot sequence that has haunted me: an image of a computer uploading files, a Thomas Jefferson quote, and then a closeup of Peters caressing a cardboard box containing her dead son’s possessions.

In 2017, Peters’ only son, a Navy SEAL, died in a freak parachuting accident over the Hudson River. Each time the film highlighted this fact, it became clearer to me that Peters found refuge in conspiracy theories to distract from the horror of her son’s death.

In 2021, Peters, then a Colorado county election official, tried to prove that the 2020 election was stolen by allegedly orchestrating a plan to copy election software from voting machines. This year, she tried, and failed, to gain the Republican nomination for the state’s top election post. Peters has pleaded not guilty to charges including identity theft and criminal impersonation, and her trial is set to begin in March.

The juxtaposition of the images of the computer, the Jefferson quote, and the cardboard box shows that Peters’ story, and that of the election denier movement as a whole, isn’t just absurd. It’s also a deeply sad tale of someone who, like many who stormed the Capitol on January 6, is convinced that her alleged crimes are actually the fulfillment of her civic duty. The movie’s nonsense was intended to warn viewers of the evil forces supposedly perverting our election system. The reality is equally alarming, but much easier to understand.

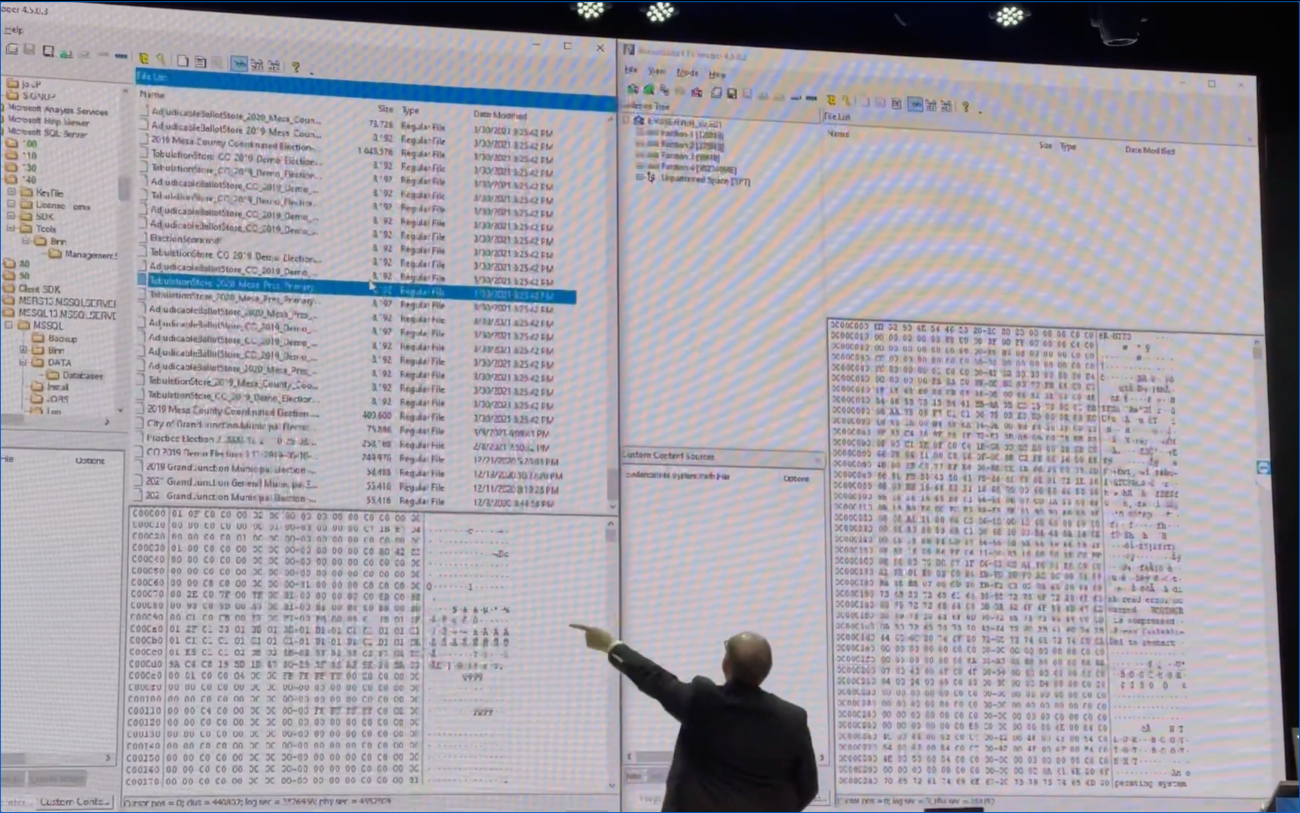

So, what is the film actually trying to argue? It’s complicated. In a dizzying series of random images of charts—reminiscent of Al Gore presenting on climate change if he forgot to turn the Excel models into actual charts—we are presented a convenient lie.

There is not enough coherence in the presentation to even begin to debunk what’s going on here. In fact, [S]election Code unearthed for me latent memories of seeing 9/11 conspiracy theory videos on YouTube in the mid-2000s. This New York Times explanation of the rhetorical methods employed by Loose Change, one of the most popular 9/11 conspiracy theory documentaries, basically fits:

It feels less like a conspiracist’s rant than an edgy PowerPoint presentation that calmly guides viewers through the evidence, using innuendo and leading questions to provoke their imaginations. Like: What was under the mysterious blue tarp carried out of the Pentagon? Were the phone calls from passengers aboard the hijacked planes faked using voice-morphing technology? If jet fuel didn’t bring down the World Trade Center, then what did?

Similarly, [S]election Code asks viewers to consider whether scanned ballot images from the 2020 elections could have been digitally manipulated to alter people’s votes, or whether voting machines were programmed to change the outcome of the election, but it never actually goes beyond wait, what if? Slick production and interviews with wacko academics seek to lend the film credibility, but it’s never revealed who is doing all this nefarious programming and manipulation, nor is it ever proven that there’s been any manipulation at all.

Throughout the film, Peters and her ally Sherronna Bishop, who purports to have served as Rep. Lauren Boebert’s congressional campaign manager, repeatedly claim to have have found evidence of voting “irregularities.” “We were heavily involved in our canvassing efforts in Grand Junction in Mesa County, and it just was getting weirder and weirder, and people were bringing affidavits regularly after every canvassing effort, and we started taking it to the clerk and recorder,” Bishop says. I’m already confused. Who was doing the canvassing? Who was bringing affidavits? What did the affidavits say?

Peters, referring to Bishop, continues, “She says, ‘We’re canvassing, we’re walking door to door, we’re finding irregularities, people that don’t live there that voted,’ and I said, ‘Just bring them to me.'” If Bishop was knocking on doors in Mesa County, how was she coming across people who didn’t live there? Were voters admitting to have flown in from Iowa specifically to vote in a western Colorado election?

Among the evidence Peters and Bishop present to suggest that the election was stolen are the fact that Dominion Voting Systems did not present its voting machines at the hacking conference DEF CON, and that candidates in a municipal election allegedly knew they had won before the official results were announced. Iron-clad reasoning.

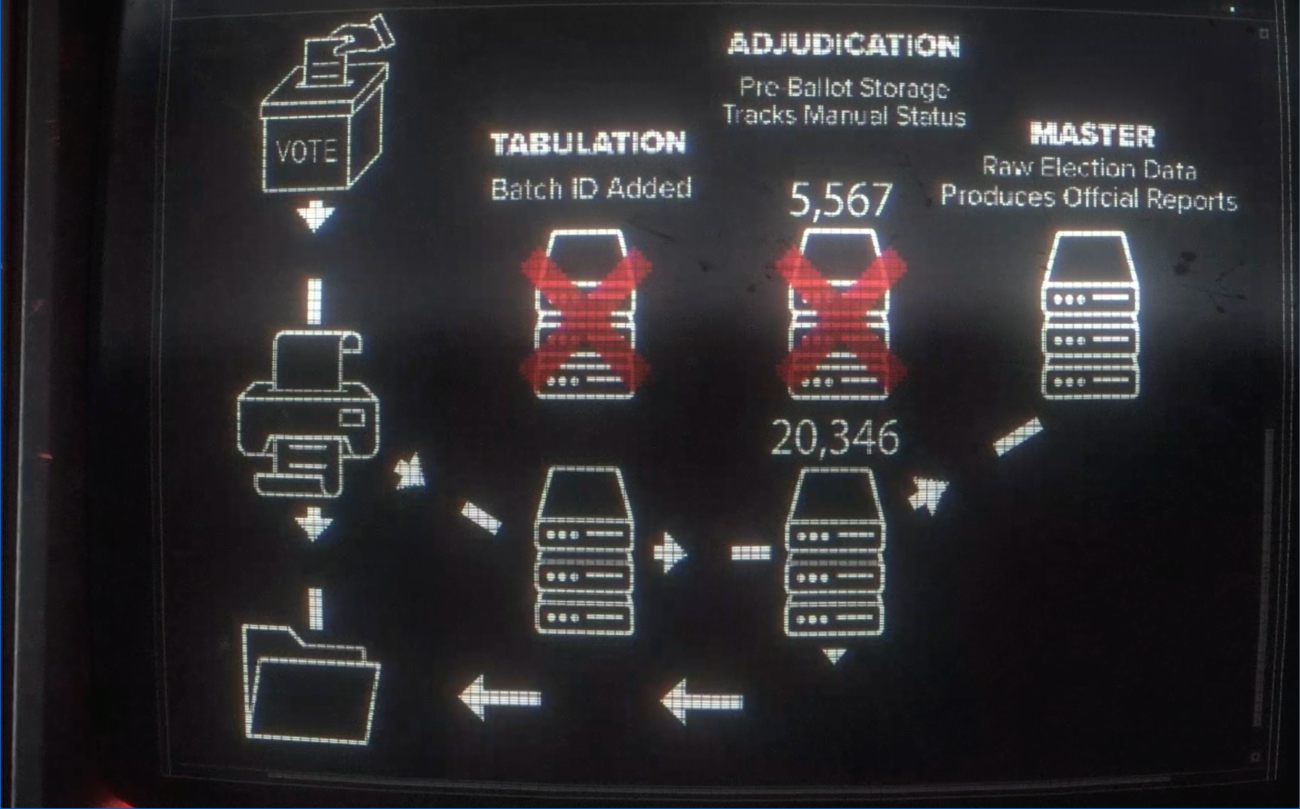

The film then uses the hard drives extracted from Mesa County voting equipment as evidence of the supposed meddling, but the exact why and how are never shown. At one point, a talking computer displays a graphic that’s supposed to explain how the stolen hard drives prove election meddling. Here is the totally inscrutable smoking gun:

Toward the end of the film, a robotic voice says, “Machines buried extra votes in Mesa County, where Donald Trump is still likely to win, and where no one is ever likely to look, and, if they did it here, there’s a chance that machines also did it counties across the state, artificially inflating Biden’s total and reducing Trump’s. So they lost the county, but won the state.” OK, prove it? Biden won more than 55 percent of the vote in Colorado.

Neither Bishop nor Peters appears to have any knowledge of coding or the ability to articulate how a series of 1s and 0s could alter election results. Voting software is the new nano-thermites.

Moreover, the film makes no mention of Mike Lindell, the MyPillow CEO who has spent millions trying to prove that the election was stolen, or Ron Watkins, the conspiracy theorist who likely played a role in posting computer files containing Mesa County election information online, or Douglas Frank, the high school math teacher who has claimed responsibility for convincing Peters that the election had been tampered with. To mention these figures would be to admit that Bishop and Peters were not simply public servants who stumbled upon a great injustice, but gullible participants in a large and well-funded scheme to convince the American public of a hypothesis for which there is no proof.

Still, in its failures, the movie is probably the most sympathetic piece of media that could have been produced about Tina Peters.

Most rational news consumers will view Peters as a deluded conspiracy theorist who allegedly perpetrated the very sort of voter fraud that Republicans claim to want to eliminate, undermining the public’s trust in our democratic institutions while she was at it. But they’ll also see another side of Tina Peters: the Gold Star Mother. Peters presents her grief as a powerful motivator, recalling that her son once described her with the words, “She fixes things.” We know that feelings of anxiety and powerlessness can prime people toward conspiratorial beliefs. Douglas Frank just happened to stumble upon an election official especially keen to fix something that wasn’t broken.