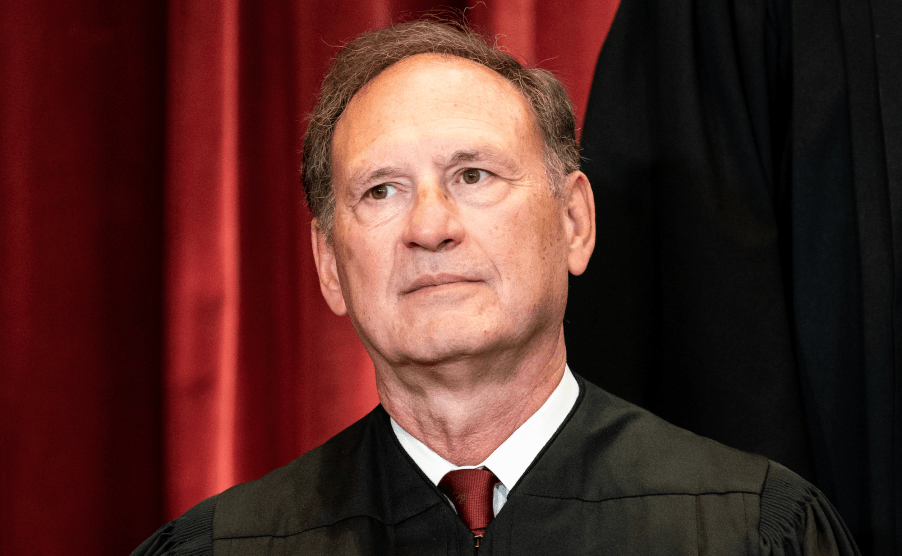

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

Last May, something almost unprecedented happened: Politico obtained a leaked draft of a forthcoming Supreme Court opinion, and published it. It was not, of course, any draft opinion—it was Samuel Alito’s majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that would end the right to abortion at the federal level. “Roe was egregiously wrong from the start,” Alito wrote in the draft. When the final version dropped in July, not much had changed.

The leak didn’t just alter, overnight, the fundamental contours of American life—it also shook the politics of the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Roberts launched an investigation to find the leaker. Ted Cruz, a former right-wing law clerk, said it must be the work of a “left-wing law clerk, angry at the direction the court is going.” Conservatives, perhaps grasping just how deeply unpopular the draft opinion was (and the final opinion would be), demanded reporters focus their attention not on the substance of the draft but on the norms that its publication had violated. Ari Fleischer, a former mouthpiece for the Iraq War who now works for Saudi Arabia, called it “an insurrection against the Supreme Court.” Ben Shapiro alleged that “there is little question that this leak is designed to create threat to the life and limb of any justice who signs onto the majority opinion.”

Little question! Other than the question of who the leaker even was, that is.

We still don’t know the answer. But on Saturday, the New York Times published another bombshell about the Court: The Rev. Rob Schenck, a former anti-abortion activist who later espoused his support for Roe, alleged that he’d been informed of the outcome of another Supreme Court case weeks before it was announced—the 2014 case in which a 5-4 majority ruled that employers could not be required to include contraception coverage in their health-care plans. And that opinion, too, was written by Alito.

According to the Times, Schenck got a heads-up about both the outcome of the case, and the fact that Alito would be writing for the majority, from a couple who had recently had dinner with the justice. Schenck provided the paper contemporaneous correspondence in which he claims to have important information about the case. He told the paper he recently passed on his account, and the documentation, to the Supreme Court because he believed it might be relevant to the ongoing investigation into the Dobbs leak.

It’s all pretty interesting, if far from conclusive. Alito denied leaking the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores decision. The woman Schenck claimed to have heard it from denied telling him. But while the alleged leak might capture the headline, the larger story might be more important—about how Schenck took in huge sums of money from conservatives to build what amounts to an influence operation on an entire branch of government. It adds up to a fascinating glimpse into how the court works, and who it really works for.