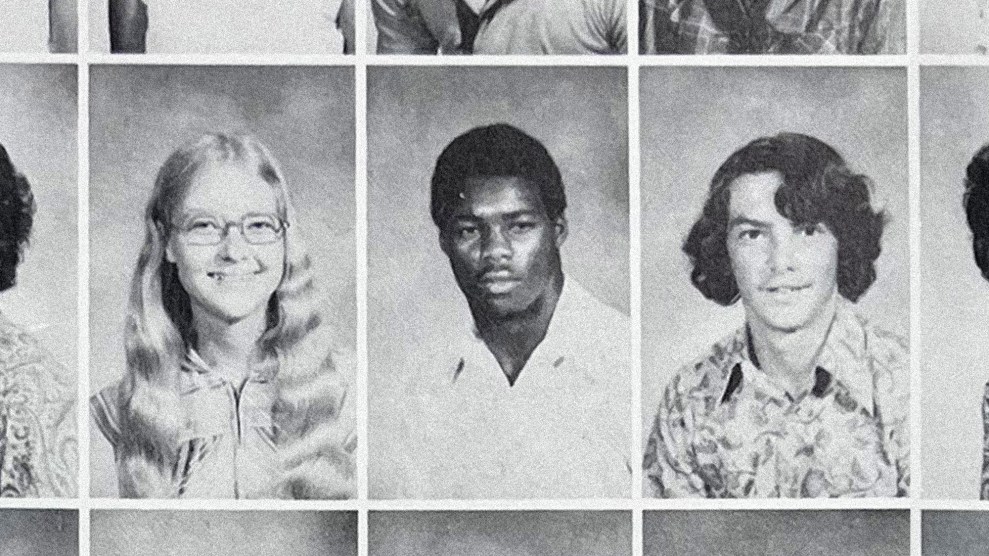

Akili-Casundria Ramsess/AP

Editor’s note: The below article first appeared in David Corn’s newsletter, Our Land. The newsletter is written by David twice a week (most of the time) and provides behind-the-scenes stories about politics and media; his unvarnished take on the events of the day; film, book, television, podcast, and music recommendations; interactive audience features; and more. Subscribing costs just $5 a month—but you can sign up for a free 30-day trial of Our Land here. Please check it out. And please also check out David’s new New York Times bestseller: American Psychosis: A Historical Investigation of How the Republican Party Went Crazy.

He’s a serial liar, a moral hypocrite, and an ignorant political novice. Yet Herschel Walker, the onetime gridiron star, still has a shot at becoming a US senator. Collecting 48.5 percent of the vote in his contest in Georgia against Democratic incumbent Raphael Warnock and placing second, Walker landed in a run-off that will occur on December 6. This final campaign of the 2022 midterms will not determine partisan control of the Senate; the Democrats took the reins, bagging 50 seats, and can count on Vice President Kamala Harris to be the tie-breaker. But this race remains important because an outright majority would afford the Democrats more power and provide a buffer in case anything happens to a member of its caucus. (Even US Senators get ill and die.) And a win for the Democrats will help them with the arduous task of holding the Senate in 2024, when they will have to defend 23 of the 33 seats up for grabs. Moreover, if the Democrats have 51 seats in the upper chamber, they would be less vulnerable to Manchinization or Sinema-osis. Every Senate vote matters.

Consequently, money and attention are flowing to Georgia for this three-week-long campaign. And this overtime face-off provides an opportunity to address an important matter that was previously only a peripheral issue in the contest: Walker should release his medical records.

It is common for presidential nominees to disclose public information about their health in some manner. There is no rule or law that compels this. But it has become a tradition—which, of course, Donald Trump, with an assist from Dr. Mehmet Oz, made a mockery of in 2016. (Remember the ludicrous letter claiming Trump “would be the healthiest individual ever elected to the presidency” written by Dr. Harold Bornstein, a gastroenterologist?) When John McCain, a survivor of cancer and torture, sought the presidency in 2008, he shared his medical records with a select group of reporters. During the 2020 campaign, Joe Biden released a summary of his medical history, including the results of a recent physical exam.

Yet candidates for lower federal office have not disclosed such information. That makes sense. A member of Congress is one of many; a president holds a singular position with the responsibility of defending the nation and the power to annihilate the world. The public’s need to have a healthy and mentally fit president outweighs any privacy concerns of one person. (Mental health experts did raise questions about Trump’s psychological fitness. He claimed he was a “very stable genius.”)

Though congressional candidates are free of this informal obligation, their health can become an issue. During the Pennsylvania Senate race this year, Oz, a Republican, called on Democrat John Fetterman to release his full medical records after Fetterman suffered a stroke. Fetterman declined. This controversy was reminiscent of when Sen. Mark Kirk, an Illinois Republican, was struck by a more severe stroke in 2012. Kirk returned to Senate, somewhat impaired, and did not make public his medical records when he ran (unsuccessfully) for reelection in 2016. Fetterman, however, convinced voters his moderate stroke was not a significant problem and smoked Oz by 4.5 points.

Walker’s case is different. He has acknowledged his personal history of violent and dangerous behavior. He played Russian roulette with a loaded gun and fantasized about shooting a delivery man who was late. “It would be no different from sighting at the targets I’d fired at for years—except for the visceral enjoyment I’d get from seeing the small entry wound and the spray of brain tissue and blood—like a Fourth of July firework—exploding behind him,” Walker wrote in his 2008 book, Breaking Free: My Life With Dissociative Identity Disorder. That’s disturbing. And his ex-wife reports that he once held a gun to her head—an episode Walker says he doesn’t remember. Walker claims these actions were all the result of DID, the mental disease he wrote about, which creates independently functioning identities within a single person.

Once known as Multiple Identity Disorder—and popularized in popular culture by such movies as Sybil and The Three Faces of Eve—the very existence of this disorder is controversial, with many health experts questioning whether it is a legitimate diagnosis. Walker, though, has cited it as an explanation (or excuse) for previous alarming behavior. That wasn’t me; my alters did it. But he asserts there’s now no reason to worry; he has been cured of DID.

These statements have escaped much scrutiny during Walker’s Senate run. As my colleague Abby Vesoulis noted in a superb piece on Walker and DID,

Despite the fact that Walker’s Senate race is one of the closest and most consequential in the nation, his DID diagnosis seldom gets more than a brief mention in media reports. Experts have largely avoided commenting publicly on Walker’s mental health, or on whether it would impact his ability to carry out the high-stress, high-profile job of serving as a United States senator. In interviews with Mother Jones, several psychiatric professionals were hesitant to comment on Walker’s condition. Some were even reluctant to discuss DID more generally.

Whether Walker had DID and whether it was responsible for his violent past, his claim of being cured warrants examination. He has proclaimed that he is “better now than 99 percent of the people in America,” and has compared his DID experience to a broken bone: “Just like I broke my leg; I put the cast on. It healed.”

Not so fast. As Vesoulis reported, Dr. David Spiegel, the associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, who is not one of the DID skeptics, told her that DID generally doesn’t just disappear without serious, long-term treatment. “There are no quick fixes,” he said. “It doesn’t just evaporate.” Yet Walker has shared few details about his treatment. In his book, he credited Jerry Mungadze, who has a Ph.D. in counselor education (not a medical degree) from the University of North Texas, for his recovery. But, as Vesoulis wrote,

Mungadze’s approach is unlike that of many mental health professionals. In 2000, he provided practitioners at a presentation with a checklist of questions they should ask patients. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, one question read: “Have they willingly, under any circumstances, vowed to follow Satan?” He also supports the use of exorcism as a therapy option, though he acknowledges it shouldn’t be the “initial step” in DID treatment. “Exorcism has a role in the treatment of some DID clients, whose clinical picture shows the need for it,” Mungadze wrote in the book, Critical Issues in the Dissociative Disorders Field: Six Perspectives from Religiously Sensitive Practitioners.

Regarding Walker’s treatment, the Journal-Constitution noted,

[E]xperts say that DID is complicated, often requiring years of therapy. Sometimes even after patients have learned to manage the condition they must still seek out help at various points in their lives. Walker’s campaign refused to answer questions about his current treatment or whether he still has symptoms.

There is no way for a voter to tell if Walker’s extreme conduct was truly caused by DID, nor if he has actually been cured. How extensive was his treatment? Aside from Mungadaze, did any credentialed mental health expert diagnose and treat Walker for DID? Does he still experience symptoms? If elected senator, might one of his supposed alters take control of him during a Senate vote or at some other important moment? Discussing someone’s mental condition can be a sensitive matter, and the stigma surrounding mental illness has been a longstanding problem. But Walker has raised this issue, which begs the question: Could he be using a purported but baseless DID diagnosis as a convenient excuse for conduct that should disqualify him from high office?

There is one simple way for Walker to answer such questions. He could release his health records. If he doesn’t want to do a full-scale dump of private material, he could follow the McCain example and make his records available to reporters. Otherwise, how can voters be assured that he’s not hiding behind a controversial medical diagnosis, and that he has been successfully treated for his violent or erratic behavior so that it would not reocur should he become a senator?

I don’t expect Walker to adopt this honorable approach. His has been a scoundrel’s campaign. He has repeatedly lied. He has questioned the Christian faith of Warnock, a pastor at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church (where Martin Luther King Jr. served as pastor). He seems to respect no boundaries of decency. After it was recently reported that Warnock used $61,000 in campaign funds to cover childcare expenses—which is allowed under campaign finance law—Walker slammed him, asking, “Why don’t he keep his own kids? Don’t have nobody keep your kids. … I keep my own.” This remark from Walker, an anti-abortion Christian fundamentalist who has fathered several children out of wedlock and who has been credibly accused of pressing his impregnated girlfriends to obtain abortions and accused by his own son of abandoning his family, set some kind of world record for hypocrisy.

In the Georgia Senate race, Democrats have tiptoed around this issue of Walker’s mental health. But it is a matter of public interest. Neither of two critical questions—was this a sound diagnosis and has he been effectively treated?—has been resolved. Should Georgia voters elect a man who allegedly threatened to kill his wife and who has admitted there were times in his life when he was under the control of various personalities and engaged in dangerous behavior? What is the basis for believing that he is now free of DID and that he won’t be plagued by his alters and driven toward violence during a stint in the Senate?

Dr. Allen Frances, chairman emeritus of the Duke University School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and a DID doubter who tried to strike it from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, believes these questions are crucial for assessing Walker’s fitness for office. He told Vesoulis, “If Herschel Walker does indeed suffer from multiple personality disorder, that should by itself disqualify him from any high office. If Herschel Walker just used multiple personality disorder as an excuse for his horrendous behavior, that should disqualify him for any high office.”

Given Walker’s uneasy relationship with the truth, his assertions about DID—he had it; it’s gone—cannot be accepted without evidence. Before this crucial election, he owes it to the voters to provide proof.