When President Biden signed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill in 2021, he committed $1.2 trillion to rebuilding the nation’s roads and bridges. The president spearheaded one of the biggest investments in infrastructure in decades: more than $42 billion for broadband equity, $30 billion for public transportation, and $148 billion for national highways. But as the 2024 presidential campaign nears, Democrats are struggling to raise voters’ awareness of the changes outlined in the law. Only 24 percent of voters even know that the law passed. So it isn’t surprising that a small but significant section has not been widely discussed: Tucked within the bill is a provision that advocates say could end drunk driving in the United States.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

The bill calls for the Secretary of Transportation to issue a rule in 2024 requiring all new passenger cars to be equipped with technology that can “passively monitor the performance of a driver of a motor vehicle to accurately identify whether that driver may be impaired” and “prevent or limit motor vehicle operation if an impairment is detected.” Put simply, if someone has a blood alcohol level above the legal limit, he or she will not be able to start the car.

Education and enforcement alone have not been enough to stop drunk driving, which is responsible for 10,000 deaths in the United States every year—each of them, as Cathy Chase, president of Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, a nonprofit alliance of safety organizations, says, representing not only “someone killed, but families…ruined.”

“It’s been a long, long slog of trying to identify new ways of making sure that people don’t make this illegal decision,” Stephanie Manning, Chief Government Affairs Officer at Mothers Against Drunk Driving, says. “We think that this is, in fact, what will eliminate drunk driving once and for all.”

There are several different technologies that could be implemented to realize the law’s vague but ambitious mandate, including a touch sensor, a breath sensor, and a camera to track drivers’ eye movements. The common denominator is that they “passively” act to detect driver impairment. Drivers don’t have to blow into a tube, and a designated driver would not be liable for a passenger’s inebriation. Nor will a driver be flagged for having taken a swig of mouthwash.

This mandate has the potential to change drivers’ behavior more directly than many previous federal safety regulations. It could stop someone when drinking leads to the poor decision to get behind the wheel, forcing drunk people to figure out alternate ways to get home. Still, many parts of the country lack access to public transportation or ride-sharing apps. Some people might have to sit in their cars until they are sober enough to start the engine.

Implementation won’t be simple, as technological hurdles and bureaucratic challenges await. And privacy concerns have called into question not only the feasibility of broadly implementing the tech in the near future, but the potential consequences of a car that tracks its drivers’ behavior.

The auto industry has been notoriously slow in implementing safety standards, a point consumer advocate pioneer Ralph Nader famously brought to the public’s attention with his 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed. But, in thinking about drunk driving, it’s helpful to remember that the public has sometimes been even slower to catch on.

The fight over seat belts is a salient example. Volvo engineer Nils Bohlin invented the three-point seatbelt in 1959. The US Department of Transportation didn’t start requiring seat belts in new cars until 1968. Even then, people didn’t want to wear them. Seatbelt use was so low that NHTSA mandated that cars manufactured in the 1974 model year be equipped with seat belt interlocks that would prevent a car from starting if the front seat belts weren’t buckled. (In 2009, the late writer Mike Davis suggested that such devices could have prevented drunk driving. “Even though the sequential logic required by the interlock to start the car was simple, it was—and still is—my conviction that drunks would have been unable to handle it,” he wrote in The Detroit Bureau.)

But consumers were outraged, and Congress quickly eliminated the requirement. Even though seat belt usage could have become nearly universal in the 1970s, its use only surpassed 90 percent nationwide in 2016, according to NHTSA.

Reducing drunk driving has been a similarly gradual process. The issue came to the forefront of the public consciousness in 1980, when 13-year-old Cari Lightner was struck and killed by a drunk driver while walking to a carnival in Fair Oaks, California. The driver had been charged with another drunk hit-and-run less than a week prior but still carried a valid driver’s license.

At the time, drunk driving could be charged as a felony only if it resulted in injury or death. Even when drivers did kill their victims, the punishments were relatively lax and didn’t always include license suspension. The driver who killed Cari was sentenced to two years in prison. He served four months before entering a work furlough program. He drove home on weekends.

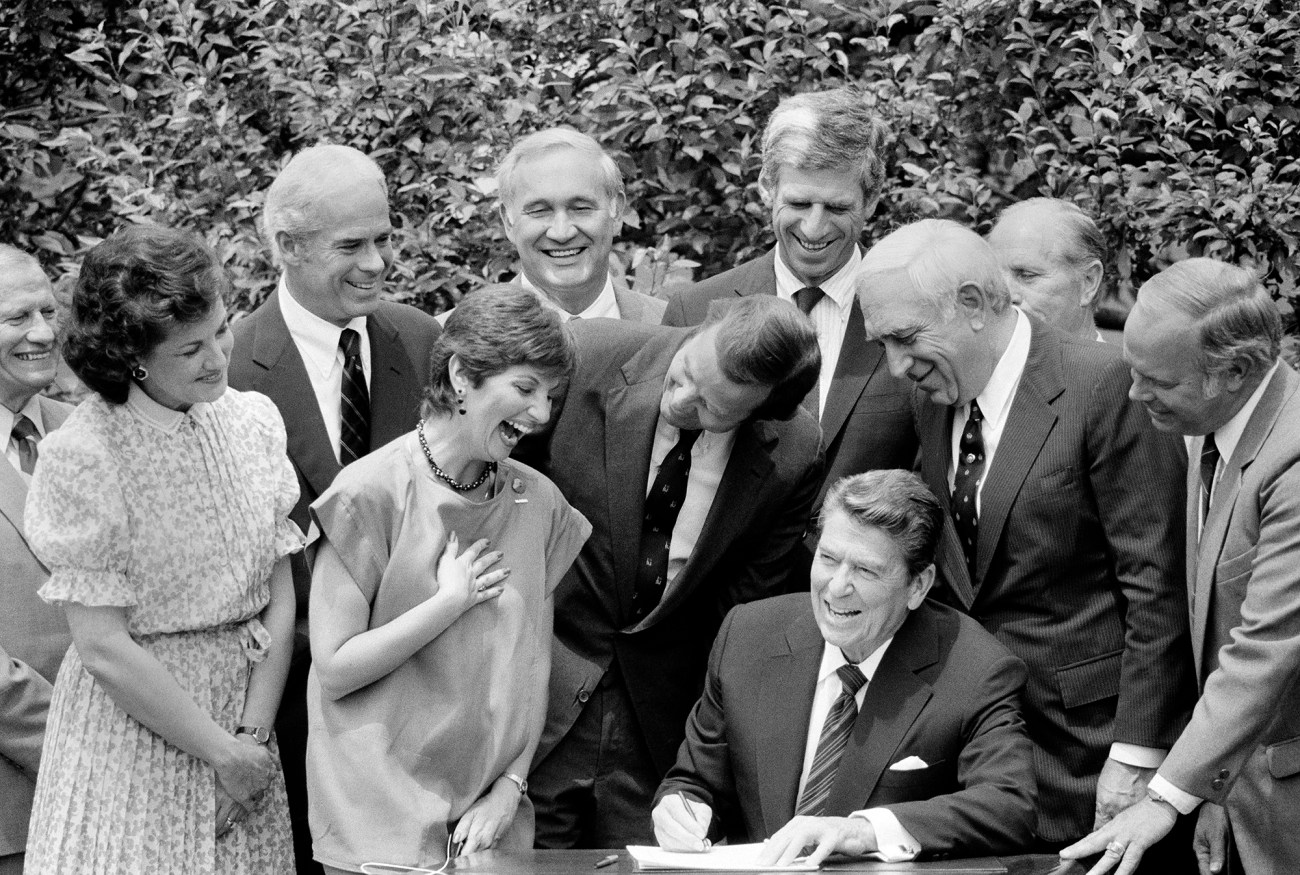

Incensed by the driver’s continued access to a license despite his recidivism, Cari’s mother, Candace, founded Mothers Against Drunk Driving in 1980 and began lobbying lawmakers for harsher punishments. MADD helped convince President Ronald Reagan to raise the nationwide drinking age to 21 in 1984. The organization helped get President Bill Clinton to set the national legal limit at .08 blood alcohol content in 2000. These laws, along with the introduction of the concept of a “Designated Driver” to TV plot lines and advertising campaigns, contributed to a steep drop in drunk driving fatalities, from roughly 28,000 nationwide in 1980 to about 10,000 in 2010. Since then, the number of people killed in drunk driving crashes in the US has plateaued, with an uptick in 2020.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan signs legislation raising the national drinking age to 21 during a ceremony at the White House Rose Garden, Washington, July 17, 1984. Mothers Against Drunk Driving founder Candy Lightner is to Reagan’s left.

AP

Now, advocates say that technology alone can bring the number of fatalities to zero. But that tech is still a ways away from being implemented. Whereas advanced safety features typically appear first in high-end cars and are then mandated for all vehicles, no cars on the market currently promise to prevent drunk driving, John Mohr, a historian of technology at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, tells me.

“One of the things that makes the anti-drunk driving mandate interesting is that currently, that technology is just not out there,” he says. “There are various theories about current technologies that could be adapted for that purpose, but the actual direct use of them to prevent drunk driving is not available to consumers yet.”

A mandate for a not-yet-viable technology has precedent in the emissions reduction requirements of the 1970s, Mohr notes. “There was a big outcry from manufacturers because they had very limited technology that was available to them at the time,” he says. But that regulatory mandate spurred innovation, and by the 1980s, cars were much more efficient. Given the history of innovation spurred by regulation, Mohr thinks it’s “very likely” that anti-drunk driving tech will be standard within the next few model years.

The quest for a technology that could prevent drunk people from starting a car officially began in 2008 with the formation of the Driver Alcohol Detection System for Safety (DADSS) program, a public-private partnership between the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and Automotive Coalition for Traffic Safety (ACTS). Rob Strassburger, CEO of ACTS, became interested in anti-drunk driving technology in 2002. At the time, he was working for an auto industry trade association when executives at General Motors and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety told him about noninvasive blood glucose monitoring systems that they thought might be able to measure blood alcohol levels.

“When I began this program, DADSS was nothing more than a wild, audacious idea,” Strassburger says. “And we have since converted that wild audacious idea into a viable technology.”

DADSS has negotiated research and development contracts with two technology providers: one that’s working on a touch sensor that could detect alcohol in a driver’s skin, and another that’s developing a sensor to passively monitor a driver’s breath. The breath detection technology is older and, Strassburger says, likely to be introduced to passenger cars first. Because alcohol absorbs light at a different wavelength than carbon dioxide, the sensor pulls a driver’s breath into a small cavity and uses infrared light to analyze the concentration of alcohol. The DADSS technology has been tested in a fleet of livery cabs and semi trucks, but it has not yet been made available to consumers.

Rather than reinventing the wheel, so to speak, some advocates also suggest that drunk driving can be prevented through minor tweaks to existing technology. Ken Snyder was already deeply familiar with the auto industry when his daughter, 37-year-old Katie Snyder Evans, was killed in October 2017 by a 21-year-old driver who had been drinking. Evans, a mother of six, had been driving to her home in Santa Clarita after visiting her premature twin daughters who were still in the hospital. “Our family was a mess for months,” Snyder says. After the twins came home from the hospital in December, Snyder was busy assembling an “army of nannies” to care for the children. “We hadn’t done anything for grieving,” he says. “And so we started working on that. But that’s when I started thinking about all the technologies.”

Snyder runs an executive education program at Utah State University’s business school and has friends in the auto industry. “I kept thinking,” he says, “with all these amazing technologies that we have, isn’t there a way to apply them to stop drunk driving?”

Since many cars already have lane assist technology, Snyder wondered why cars couldn’t be programmed to pull over when someone is driving erratically. Eye-tracking is a common feature in luxury vehicles. Why not ensure that drivers are keeping their eyes on the road? “I started calling my friends, and they told me, ‘Oh, yeah, we could apply that to drunk driving. We just don’t,’” Snyder says. “‘The car makers don’t want it.’”

After months of research, Snyder reached out to MADD and, with the organization’s help, began lobbying Congress to pass a law compelling automakers to act. The legislation, sponsored by Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.) and Sen. Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) received bipartisan support and was enacted in November 2021 as part of the infrastructure law.

“If any good was going to come out of our daughter’s death,” Snyder says, “it was going to be, let’s try to make it so that other families don’t have to go through the hell that we went through.” And the infrastructure law’s mandate, he says, has been instrumental in getting the auto industry on board.

The infrastructure law requires automakers to have complied with the Secretary of Transportation’s rule two years after it’s issued. But the law also offers the Transportation Secretary the ability to push back its deadline if he or she submits a report to Congress explaining why. Strassburger is confident DADSS can hit the law’s deadline, and that at least one version of the technology will be available for the 2027-28 model year.

Still, the idea of eyes being tracked or breath monitored while driving is fraught with privacy concerns, especially in an age of increasing surveillance in various aspects of our lives, from our internet browsing history to our performance in the workplace to how poorly we sleep. Like red light cameras, which photograph the license plates of drivers who run stop lights, this technology raises the question of whether increased safety comes at the expense of privacy.

Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, points out that anti-drunk driving systems could collect myriad information about people’s bodies, in addition to data that cars already track, such as drivers’ location history and phone logs. In 2019, the Washington Post hacked a Chevy and discovered that the car was tracking details as minute as braking patterns and sending that information back to General Motors.

“The problem is they have the potential to gather information about people’s bodies in ways that cars don’t currently do,” Stanley says. “Are [drivers] smoking? Are they kissing somebody while they’re parked? Are they eating while they’re driving? The list goes on and on.”

“There are parties hovering behind this technology that are hungry for data, such as automakers, and companies that collect data from cars,” Stanley says. “A privacy-protecting version of this technology is not going to happen by itself. It’s going to have to result from vigilance by advocates, including advocates for safer roads who don’t really have an interest in creating new vectors for spying on people in their cars.”

Indeed, some lawmakers have introduced legislation aimed at protecting drivers’ privacy—not by outlining which information automakers can and can’t collect from passengers, but by overturning the rule entirely. Last year, Sens. Mike Rounds (R-SD), Mike Braun (R-Ind.), and John Cornyn (R-Tex.) introduced a bill that would repeal the anti-drunk driving provision altogether, under the guise of “safeguarding privacy.” The advocates I spoke to said that the bill did not have the political backing to move forward. Representatives for the senators have not responded to requests for comment.

Each of the advocates I spoke to insisted that the technology should not be designed to store private information—or to report it to the police. “Cars are an extension of ourselves,” Strassburger says. “That’s the last hurdle that we have to cross with this technology. This technology is possible. But whether or not it’s viable is whether or not it’s used by consumers. And if they don’t accept it, it won’t get used, and we won’t see the safety benefits.”

Stanley says that privacy and safety are not necessarily mutually exclusive. “It can be designed in such a way that it uses one technology or another to effectively identify people who are seriously drunk and stop them from driving while not retaining or allowing the sharing or accessing of any of the particular data that goes into the decision-making algorithm,” he says. “There’s plenty of ways this can be engineered in such a way that it could not pose any threats to privacy, while still being effective.”

Still, there are other ways we can allow people, even drunk people, to get to their destinations with little risk of killing anyone. When I spoke to University of Virginia historian Peter Norton about jaywalking last month, he mentioned that some high-tech car features, like pedestrian detection, can reinforce drivers’ complacency and obsession with driving fast. I asked him what he thought about anti-drunk driving tech.

“There’s certainly some tech that absolutely is worth pursuing because it can indeed make our horrifying traffic safety record a little better,” he said. “What disturbs me about this whole trend is, it’s very easy to misunderstand our problem as finding the tech we need to protect the status quo. And that prevents us from asking if the status quo itself is right. The status quo, in a couple of words, is car dependency.”