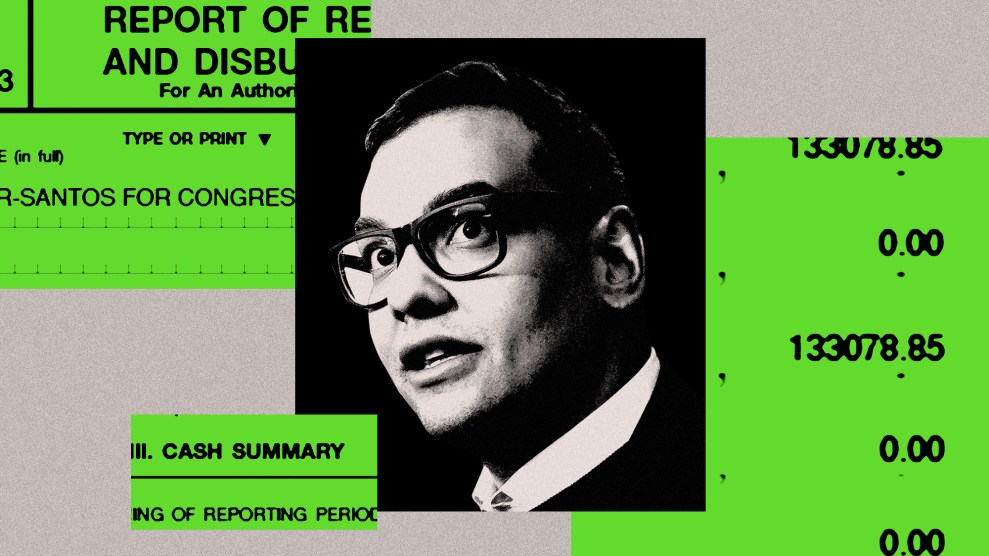

Mother Jones illustration; Aaron Schwartz/Xinhua/Getty

On Tuesday evening, federal prosecutors charged already-indicted and disgraced Rep. George Santos (R-N.Y.) with several new crimes, including campaign finance violations for a fake-donor scheme exposed by Mother Jones earlier this year. These new counts added to the preexisting indictment also include wire fraud and identity theft. The feds claim that Santos used his donors’ credit cards to make unauthorized transactions that ended up transferring funds to his own campaign, the campaigns of other candidates, and his own bank account.

“Santos allegedly led multiple additional fraudulent criminal schemes, lying to the American public in the process,” said FBI Assistant Director in Charge of the New York Field Office James Smith.

Earlier this year, Mother Jones broke the news that Santos had reported receiving what appeared to be fake donations during his 2020 and 2022 congressional campaigns—a straightforward violation of federal campaign finance laws. His former treasurer, Nancy Marks, confirmed Mother Jones’ reporting by pleading guilty last week to having helped Santos pull off this scam in order to falsely inflate his campaign’s fundraising totals. Marks is facing a recommended prison sentence of up to four years. In May, Santos pleaded not guilty to 13 other charges.

After the New York Times revealed in December that the newly elected congressman had made up much of his résumé, the list of lies that he had told about his career and personal history continued to expand. Santos falsely claimed that he wrecked his knees playing on a college volleyball team that “slayed” Harvard and Yale; that he had helped produce Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, a musical that lost tens of millions of dollars; that he was Jewish and that his ancestors had fled the Holocaust; that four of his employees died in the Pulse nightclub shooting; and that the attacks on 9/11 had taken his mother’s life.

These fabrications, while notable, were not criminal. Lying on a campaign finance report, however, is. When we examined Santos’ campaign finances from his first run for office in 2020, we found that many of his top-dollar donors did not seem to exist. For example, Victoria and Jonathan Regor were each recorded on his campaign’s filings with the Federal Election Commission as having donated the legal maximum of $2,800 in the general election. Public records, though, showed nobody named Victoria Regor or Jonathan Regor anywhere in the United States, and the New Jersey address listed for them did not exist.

Post by @motherjonesmagView on Threads

In another case, a retiree named Stephen Berger was listed as living on Brandt Road in Brawley, California. Public records showed that William Brandt was the real resident of that address. A spokesperson for Brandt told us that Brandt had never donated to Santos, that no one named Stephen Berger had ever lived at the address, and that he did not know anyone by that name.

In other cases, the apparent fraud was comically sloppy. One of the major donors listed at a fake address was Rafael da Silva. That happened to be the name of a Brazilian soccer player who had played near where Santos once lived in the Rio de Janeiro area. Da Silva’s nonexistent address was 15 West 57th Street—another curious coincidence. Sam Miele, Santos’ fundraiser at the time, appeared to have named his company, the One57 Group, after the luxury tower at 157 West 57th Street. (In August, Miele was indicted for impersonating a top aide to Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the California Republican, while soliciting donations.)

We also reported on the suspicious presence within Santos’ FEC filings of large donations from relatives of Santos and Marks, who was also his business partner. This included Santos family members whose occupations were recorded in filings as mail handler, painter, and student. A Santos relative who was listed as having given $5,800 told us that they did not make any contribution to the campaign. Marks and her relatives made large donations to Santos’ 2022 campaign that totaled more than $30,000. This included Marks’ two children who were 19- and 22-year-old students.

The superseding indictment alleges that Santos used the fake donations and a fake loan to attract additional support from a national Republican committee during the 2022 race. His campaign had to show that it had raised $250,000 to qualify for this assistance.

On January 31, 2022, Santos texted Marks that he was “lost and desperate” and asked her “what did we figure out about the report.” That same day, the Santos campaign submitted a report to the FEC that listed $53,200 in fake donations from relatives, including the ones Mother Jones later identified. “Contrary to the representations made by” Santos, the new indictment states, “none of the family members of [Santos] and Marks had made, or ever did make, the listed contributions.”

Prosecutors also allege that a $500,000 loan the Santos campaign reported receiving from the candidate in March 2022 never actually occurred. Santos appears to have tried to keep members of his own campaign in the dark about that fake loan. In March 2022, a person affiliated with the campaign texted Santos, “Did you get the wire done for the [first quarter] loan?” Santos replied, “That’s getting done tomorrow and it’s not a wire, banker check.” Santos had less than $8,000 in his personal and business bank accounts at the time, according to the latest indictment.

The new indictment describes another scheme in which Santos allegedly used a donor’s credit to make nearly $16,000 of donations to his campaign and associated political committees. These donations exceeded legal limits on individual contributions to a candidate. To help get around that, Santos listed some of these donations under the name of a relative who is not named in the indictment. (FEC records show that it was his sister, Tiffany Devolder.)

Santos later used the donor’s credit cards to attempt to make at least $44,800 in unauthorized charges, according to the indictment. In one case, Santos used the card to funnel nearly $12,000 to a company he controlled. Later that day, he transferred almost all of that money to a personal bank account.

The original indictment of Santos charged him with using donations intended for a super-PAC supporting his campaign to pay for luxury goods and other items, committing unemployment insurance fraud, and making false statements on his congressional financial disclosure forms.

At the time of that indictment, prosecutors curiously sidestepped the fake donations. But when Marks last week pleaded guilty to a charge related to the fake-donor scheme, as well as the plot to record the false $500,000 loan, it became clear that federal prosecutors would add similar charges to their case against Santos. The charging documents in the Marks case alleged that Marks had committed her crime in full partnership with Santos.

In trying to explain irregularities with his campaign’s FEC filings, Santos has maintained that Marks went “rogue.” Marks’ plea directly contradicts this claim.

Santos is set to return to court on October 27.