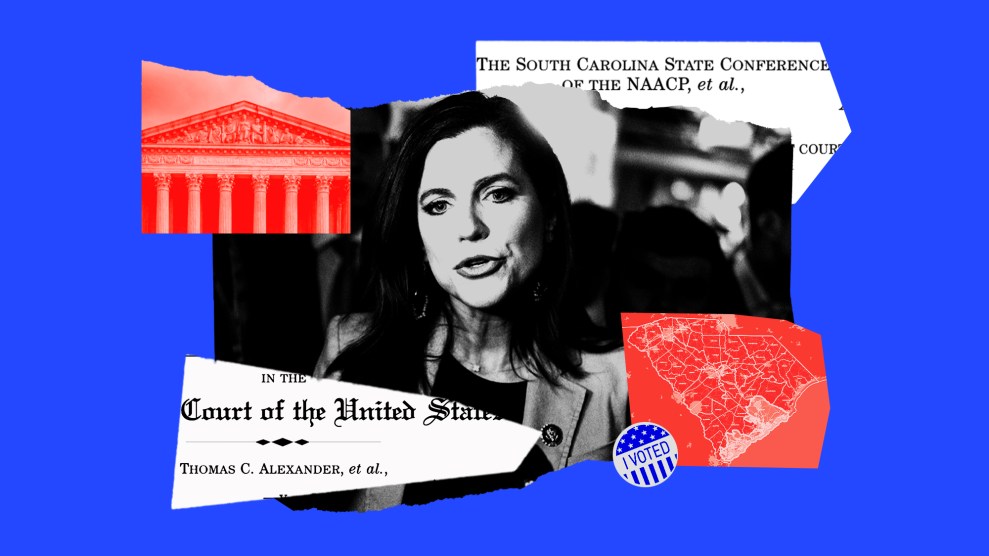

Mother Jones illustration; Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Zuma; Tim Mossholder/Unsplash

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments on Wednesday in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, a case that could help decide which party controls the House of Representatives in 2024, along with the future of minority representation and voting rights litigation in the South.

In 2018, Joe Cunningham became the first Democrat in nearly 40 years to win South Carolina’s 1st congressional district, which is centered around Charleston.

Two years later, Republican Nancy Mace defeated Cunningham by one point. But that victory was too close for comfort for Republicans.

When South Carolina’s GOP-controlled state legislature redrew the state’s congressional districts in 2021, a GOP state senator from the area said he wanted to “give the district a stronger Republican lean.” Republicans accomplished that goal by moving nearly 30,000 Black voters in Charleston County (62 percent of the county’s total Black population) from the swing 1st district to the safely Democratic seat of longtime Rep. James Clyburn, one of the most powerful House Democrats. (ProPublica reported that Clyburn worked with Republicans to add more Black voters to his district to shore it up; he has denied this and filed a brief in support of civil rights groups.)

In 2022, Mace won re-election by 14 points. Last week she made headlines by becoming one of eight House Republicans who voted to oust House Speaker Kevin McCarthy.

Civil rights groups, led by the South Carolina NAACP, challenged the GOP’s map and in January a three-judge panel struck down the district as a “stark racial gerrymander.” Republicans promptly appealed to the Supreme Court.

South Carolina said the district drawn for Mace was motivated by politics, not race. “District 1 is not a racial gerrymander,” said John Gore, an attorney at Jones Day who represented South Carolina. (Gore was head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under Donald Trump and one of the driving forces behind the Trump administration’s failed effort to add a question about citizenship to the 2020 census, pushing the bogus argument that it was needed to better enforce the Voting Rights Act.) His argument in the Alexander case could be used to justify nearly any instance of racial gerrymandering, making it next to impossible to strike down maps that discriminate against voters of color.

The court’s conservative majority appeared sympathetic to South Carolina’s defense that it was difficult to disentangle race and politics. Chief Justice John Roberts told Leah Aden, senior counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, that civil rights groups faced a “high burden” and “you’re trying to carry it without any direct evidence, with no alternative map, with no odd shaped districts.” A ruling vacating South Carolina’s map based on what he termed “circumstantial evidence,” Roberts said, “would be breaking new ground in our voting rights jurisprudence.”

The Roberts Court has already made it very difficult to strike down gerrymandered maps, ruling that partisan gerrymandering cannot be challenged in federal court, and has reliably sided with Republicans in voting rights disputes. As Justice Elena Kagan noted, the Court’s 2019 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause preventing federal courts from invalidating partisan gerrymandering gave states like South Carolina a green-light to enact racial gerrymanders but claim they were simply done for partisan reasons.

One surprising exception to the Court’s hostility to voting rights came last summer, when it invalidated Alabama’s congressional map because it did not include a second majority-Black district in a state that is 27 percent Black. The new seat ordered by the courts is expected to elect a new Black member of Congress from Alabama and boost Democrats’ chances of retaking the House. These developments have raised hopes that the conservative majority may be open to policing racially gerrymandered maps in a new way.

In Alabama and South Carolina, Republicans pursued different strategies to dilute Black voting strength. Republicans in Alabama simply ignored Black political power by refusing to draw a second majority-Black district. In South Carolina, “Black voters were used as political puzzle pieces in the state legislature’s attempt to ensure and insulate the legislative majority party’s power,” says Mitchell Brown, senior voting rights counsel at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice.

In Alabama, Republicans didn’t consider race enough. In South Carolina, they considered race too much. In that sense, civil rights groups are making an argument often used by Republicans—that race should not be the driving force in drawing political lines—to argue against racial gerrymandering.

“State legislators are free to consider a broad array of factors in the design of a legislative district, including partisanship, but they may not use race as a predominant factor and may not use partisanship as a proxy for race,” the three-judge panel wrote in South Carolina.

The Supreme Court similarly ruled in 2017 in Cooper v. Harris that a district is likely unconstitutional if “race was the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a particular district.”

“No party disputes Cooper’s basic legal rule that absent a compelling interest, race cannot predominate in line drawing, even as a means to achieve a partisan goal,” said Aden.

But in the Alexander case oral arguments, the Court’s conservative majority seemed to suggest that its recent decision striking down racial gerrymandering in Alabama may be a one-off.

Civil rights groups have asked the Supreme Court to issue a decision by January 1, 2024, so that new lines could take effect for the 2024 election if the lower court decision is upheld.